We depend on access to water and cannot operate without it.

Access to safe, clean water is a basic human right and essential to maintaining healthy ecosystems. Our Water Stewardship Position Statement outlines BHP’s vision for a water secure world by 2030, which is aligned with the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals.

Water Stewardship Position Statement

Our Water Stewardship Position Statement expresses BHP’s commitment to and advocacy for water stewardship.

Our ambition

Our Water Position Statement was developed following broad internal and external engagement and is aligned to the UN Sustainable Development Goals and other initiatives such as the UN Global Compact’s CEO Water Mandate (CEO Water Mandate) and the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM) Water Position Statement.

It describes the challenges facing fresh and marine waters across the globe and seeks to reinforce that it is everyone’s responsibility to take action together. For BHP, this means improving our own water management and actions to strengthen water governance beyond our operated assets.

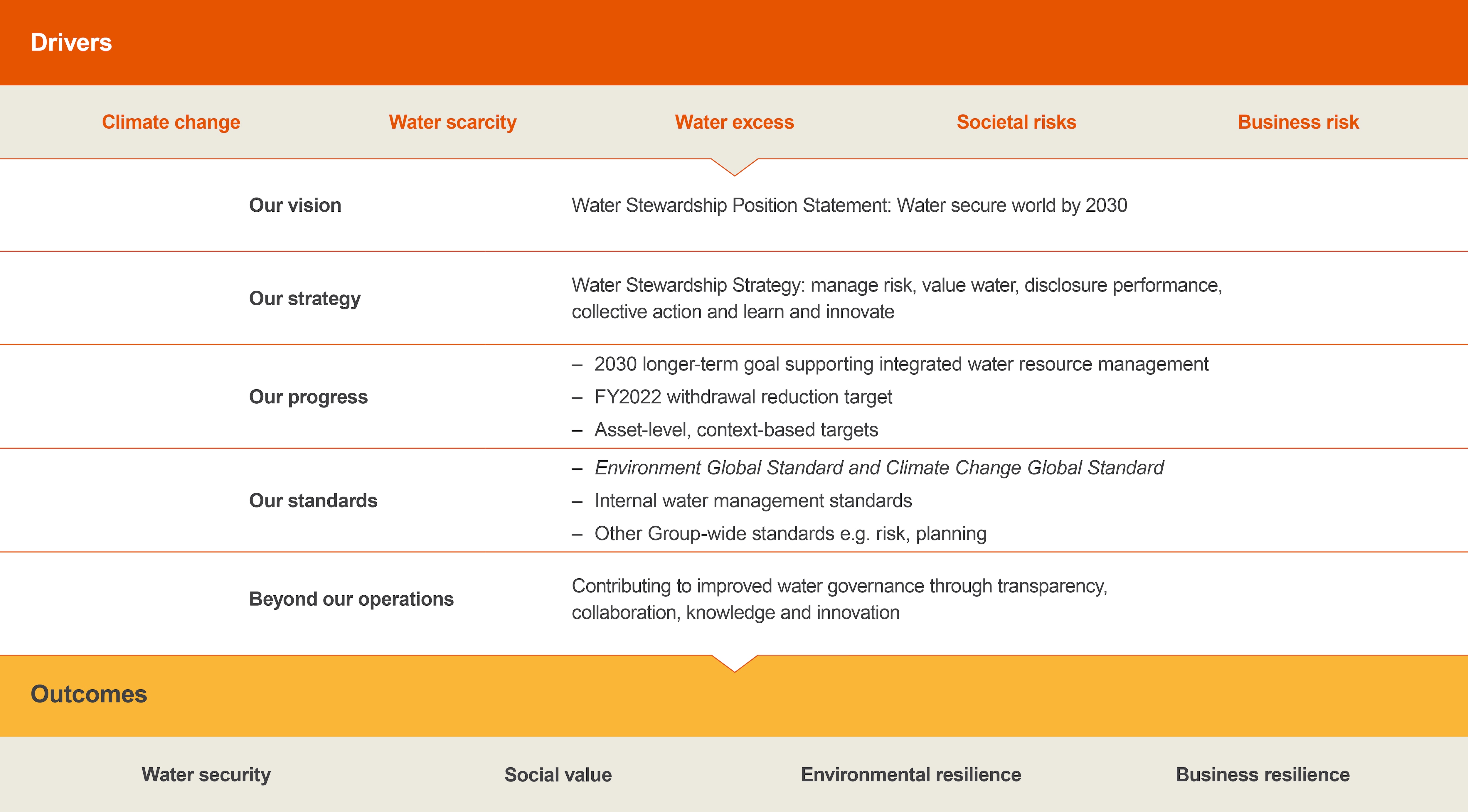

Our vision for water is supported by our Water Stewardship Strategy and our goals and targets. Our approach to water stewardship is represented in the figure below.

Our approach and position

BHP’s approach to water stewardship

Our Water Stewardship Strategy aims to improve our management of water, increase transparency and contribute to the resolution of shared water challenges.

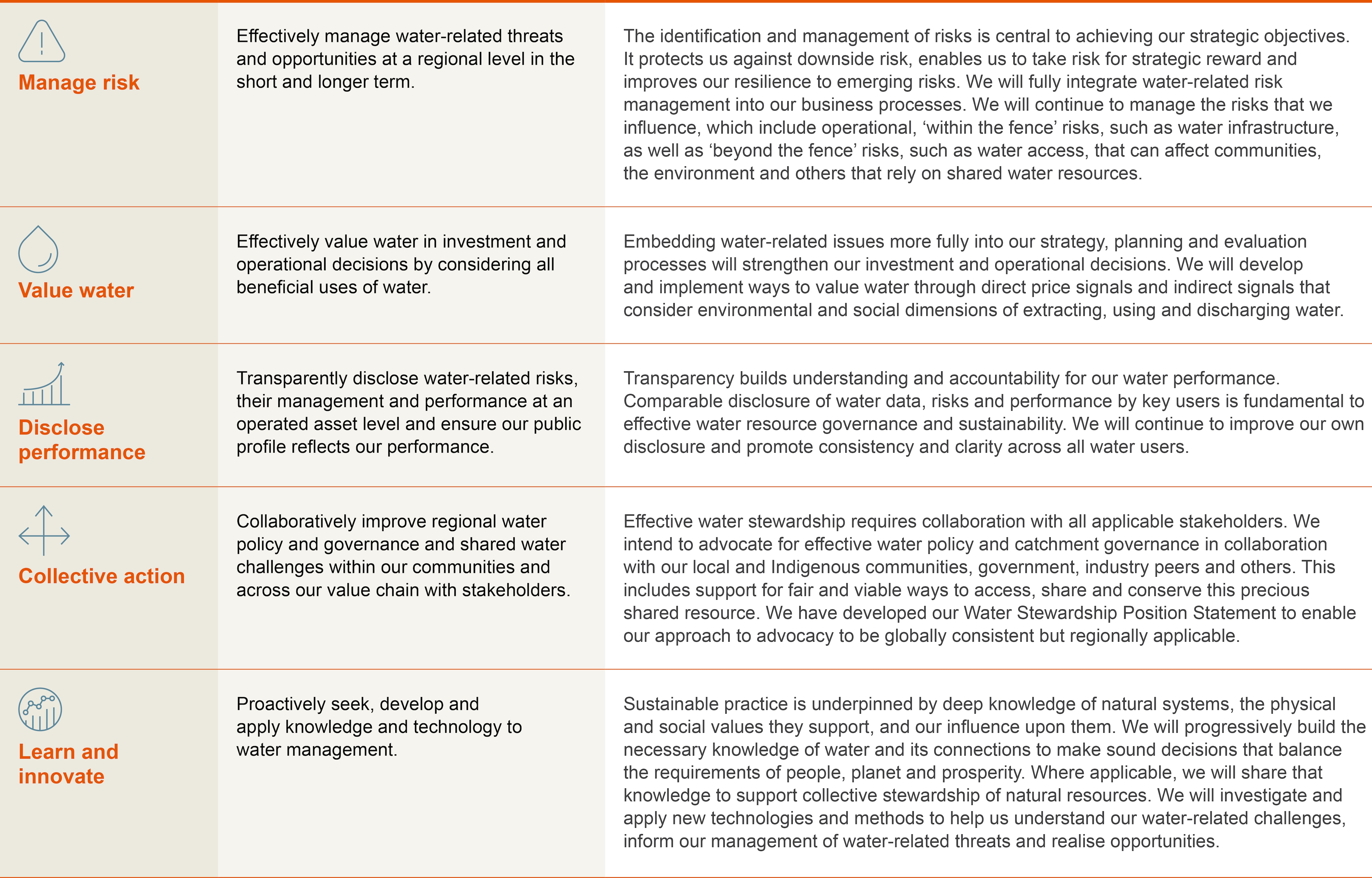

Our strategy’s pillars are shown below.

The five pillars of our Water Stewardship Strategy

We have evolved our water-specific public targets over more than 15 years – from intensity metrics (water used per tonne of product), to a combination of risk-based targets and absolute volume reduction targets to regional context-based water targets.

Over the period of FY2018 to FY2022, we had a public water-related sustainability target to reduce FY2022 freshwater withdrawal1 by 15 per cent from adjusted FY2017 levels across our operated assets. We exceeded this with a 29 per cent reduction. During the FY2018 to FY2022 period, we also increased our use of non-freshwater sources in some of our regions.

We have continued to refine our approach to target and goal setting. Since FY2020, BHP has engaged third parties (such as universities) to undertake Water Resource Situational Analysis (WRSAs) to establish a collective view on the shared water challenges within the regions or catchments where we operate. These WRSAs have shown that while minimisation of freshwater withdrawal remains important, in some of the regions where we operate freshwater withdrawal is not the key water-related risk or challenge for the region.

More information on the WRSAs and CBWTs can be found at Shared water challenges and in the below Performance section.

Footnotes:

1 Withdrawal is defined as water withdrawn and intended for use (in accordance with the ICMM guidance). Fresh water is defined as waters other than seawater, wastewater from third parties and hypersaline groundwater. Freshwater withdrawal also excludes entrained water that would not be available for other uses. These exclusions were made to align with the target’s intent to reduce the use of freshwater sources that are subject to competition from other users or the environment. The FY2017 baseline data was adjusted to account for the materiality of the worker strike affecting water withdrawals at Escondida in FY2017 and improvements to water balance methodologies at WAIO and BMA in FY2019, which included alignment of water balances to ICMM guidance. Discontinued operations (Onshore US-operated assets and Petroleum), BHP Mitsui Coal (BMC) and non-operated joint ventures were excluded.

-

Governance and oversight

-

Engagement

-

Disclosure

-

Performance

For information on our governance of environmental performance and nature, including water, refer to the Nature and environmental performance webpage, and for information on broader sustainability governance, including the role of the BHP Board and Management, refer to the BHP Annual Report 2025, Operating and Financial Review 9.2 – Sustainability governance and the Sustainability approach webpage.

We use our Water Stewardship Position Statement, our Water Stewardship Strategy and our standards (including our Environment Global Standard, Closure and Legacy Global Standard and internal water management standard) to manage water at BHP. Each of our operated assets has assigned responsibilities for its key water management activities and this is a requirement of our mandatory minimum performance requirements for water management.

Governance of our water activities is essential as we cannot operate without water. We use water in many ways, including:

- extracting it for activities including ore processing, dust suppression, ecosystem irrigation and processing mine tailings

- managing it to access ore through dewatering (extraction of water from below the water table to allow access to ore) and to prevent mining waste contaminants leaving our legacy assets (legacy assets refers to those BHP-operated assets, or part thereof, located in the Americas that are in the closure phase)

- providing drinking water and sanitation facilities for employees and townships

- discharging water back to the receiving environment

- interacting with marine water resources through our port facilities

- utilising marine water for desalination

We have a responsibility to effectively manage and have governance over our water interactions and avoid or minimise our adverse impacts on water resources. Effective water stewardship must begin within our operated assets. From there, we can more credibly collaborate with others toward solutions to shared water challenges.

We also recognise the importance of working with others to enable more effective water governance and stewardship across the communities, regions and countries where we operate.

Responsible water management will ultimately make BHP more resilient and will contribute to enduring environmental and social value.

Water challenges faced by BHP may include water scarcity or high variability in water supply due to climatic conditions or cumulative use or impacts within a catchment. These challenges need to be managed appropriately to avoid or minimise actual and potential adverse impacts and support positive impacts to the environment, communities and BHP’s ongoing viability.

We seek to identify and assess opportunities to reduce stress on water resources from our operations and to collaborate with others on challenges and opportunities, such as water scarcity or high variability in water supply. For example, we have a CBWT milestone at our Copper South Australia asset to partner with the South Australian Government on the coastal desalination Northern Water Supply Project.

BHP has established cross-functional teams to implement our approach to water stewardship at Group and asset levels. These teams include representatives from Planning; Engineering; Strategy; Environment; Water; Closure; Community; Corporate Affairs; Operations; Risk; and Legal.

In addition to regular stakeholder engagement processes, we undertake specific stakeholder engagement activities related to water stewardship. The following table outlines the key stakeholders engaged, how they were engaged and the topics on which they were engaged.

| Stakeholder | Forum / Topic |

| Various local stakeholders in our operating regions, including community groups, Indigenous groups, government (local and regional), industry members and representative bodies, and research institutes. | We undertake stakeholder engagement to develop the WRSAs in our operating regions. We asked stakeholders what they value about water resources, and their views of the challenges and collective action opportunities to preserve those values. In FY2025, we released an addendum to our Andean aquifers and San Jorge Bay WRSAs in the operating regions of Escondida and Pampa Norte, and a new WRSA for the Hunter River Catchment where NSWEC lies. |

| ICMM | BHP contributes to the ICMM through its Closure and Water Peer Network. This connects member companies to share lessons and best practices. |

| CEO Water Mandate |

BHP is a signatory to the CEO Water Mandate and member of the Steering Committee. We support the CEO Water Mandate’s program and particularly promote the priorities for broader regional spread (e.g. into Asia Pacific and South America), greater involvement of resource industries, linking water with climate change and biodiversity programs and pragmatic approaches. |

| Minerals Council of Australia (MCA) | BHP is an active member of the MCA’s Water Working Group. Through the MCA we contributed to the Australian Government’s review of the National Water Initiative and the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. |

| Water roundtables | We undertake engagement with conservation groups, thought leaders and policy-makers to provide an opportunity for input into our water stewardship program and direction. We plan to re-instate annual roundtables and extend the scope to cover nature more broadly. |

| Water-related conferences | We continue to participate in and present at water-related meetings and conferences, such as Water in Mining Global Summit, with the intent to share our experiences and learnings, and gain insight into current and future focus areas. |

Our water disclosures here and in the BHP Annual Report 2025, Operating and Financial Review 9.9 – Nature and environmental performance have been prepared predominately pursuant to the ICMM Water Reporting: Good practice guide (2nd Edition) (2021) (ICMM guidance) minimum disclosure standard, which is an international water accounting framework that enables comparable water data across the mining and minerals sector.

Our water reporting also considers other relevant frameworks. BHP is a signatory to the CEO Water Mandate and our disclosures here and in the BHP Annual Report 2025, Operating and Financial Review serve as BHP’s Communication of Progress against the core elements of the CEO Water Mandate.

For information on our approach to broader nature-related disclosure frameworks, refer to the Disclosure section of our Nature and environmental performance webpage.

We have reported our water withdrawals and discharges and had water-specific public targets in place for more than 15 years since the establishment of the Minerals Council of Australia’s Water Accounting Framework (WAF).

We updated our reporting in FY2019 to align with the ICMM ‘A Practical Guide to Consistent Water Reporting’, and since FY2022 have aligned our reporting with the updated ICMM guidance, ‘Water Reporting: Good Practice Guide (2nd Edition)’.

Since FY2021, we have reported the proportion of withdrawals, discharges and consumption that occurred in areas of water stress, as defined by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Water Risk Filter physical risk ratings (see BHP and basin risk in the Water-related risk section for a full overview) and since FY2022, we have aligned our disclosure of other managed water (previously called diversions) to the updated ICMM guidance, which included the change in terminology and disclosure of this metric by both quantity and quality. In FY2025, we introduced combined quantity and quality metric disclosure.

Definitions of water metrics, sources, types and detailed water data by asset are provided in the BHP ESG Standards and Databook 2025, the BHP Annual Report 2025 Glossary and in the ICMM Guidance and WAF.

The WAF and the ICMM water quality categories do not completely align with the generalised definition of fresh water, which is typically classified on the basis of salinity alone and related to drinking water guidelines (with a threshold of 1,000 mg/L Total Dissolved Solids). The majority of the significant volumes of water accessed and managed by mining and metals operations is not for drinking water end use and therefore using the drinking water definition of high-quality water for reporting purposes would place inappropriate emphasis on a relatively small proportion of water managed. The WAF and ICMM guidance defines more specifically high-quality water for application to the mining and metal sector, which is water with low levels of salinity, bacteria, naturally occurring contaminants (e.g. dissolved metals) and anthropogenic pollution, and relatively neutral (pH 6 – 8.5). The definitions for water quality types are provided in the BHP ESG Standards and Databook 2025 and BHP Annual Report 2025 Glossary, and a detailed description is available in section 2.2.4 WAF. BHP has continued to group water quality into three categories in line with the WAF: Type 1 and Type 2 defined by the WAF equate to high-quality water defined in ICMM guidance, while the Type 3 WAF definition equates to low-quality water under the ICMM guidance.

The ICMM guidance and the WAF make use of a site water balance to establish a water account. A generalised water balance ‘equation’ requires water inputs to equal the outputs plus any change in storage. That is: water withdrawals/inputs = water discharges + water consumption +/- change in water storage.

We recognise water balances contain a degree of uncertainty and, over a given period, the reported withdrawal may not be in balance with the sum of discharge, consumption and net storage change. The ICMM guidance requires that, at a site level, the delta storage derived by mathematical balance broadly reconciles with the actual change in volume of water in storage over the same period.

The general practice in the mining sector (which is accepted by the ICMM guidance and WAF) is to force a balance in water accounts, so that inputs equal outputs plus consumption plus or minus change in storage, by creation of a balancing point, for example assumed evaporation or change in storage volumes.

In some of our sites we have elected not to artificially adjust any dimensions of the water balance to force a balance in our water accounts. Instead, we have chosen to retain the calculated differences in the water balance and recognise the differences represent levels of uncertainty within the water balance. This understanding of uncertainty is considered in our ongoing water management decisions and guides the ongoing improvement of our water balance models, which are continually developing as we apply new measurement points, enhanced measurement methods, and improved practices to estimate indirect data (for example the runoff from rainfall, evaporation and seepage volumes). This approach is aligned with the intent of frameworks, including the ICMM guidance, WAF and GRI, that recommend water balances be used as a live management tool that can identify ongoing improvement in water accounts.

We use the WAF accuracy statement to provide an indication of the accuracy for each metric by classifying them according to whether they are measured directly, simulated or estimated. We use the accuracy statement as one tool to identify data gaps and opportunities for more or improved flow measurement in our water balances that inform our water management decisions. Where possible, we endeavour to maximise direct measurement and minimise estimation. We simulate or estimate elements that are challenging to measure directly, such as evaporation, seepage from tailing storage facilities and rainfall runoff quantity and quality.

Water stewardship strategy progress

| Water Stewardship Strategy pillar | What we did in FY2025 |

|

Manage risk Effectively manage water-related risks (both threats and opportunities) at a regional level in the short and longer term |

For more information on BHP’s Risk Framework refer to the BHP Annual Report 2025, Operating and Financial Review 7 – How we manage risk and the Water-related risks section on this webpage. |

|

Value water Effectively value water in investment and operational decisions by considering all beneficial uses of water |

We have continued our work on understanding and managing the value of nature to business and communities. For more information refer to the ‘valuing natural capital’ section of our Biodiversity and land webpage |

|

Disclose performance Transparently disclose water-related risk, management and performance at an asset level and ensure our public profile reflects our performance |

We continue disclosure of our current water performance at an asset level on this webpage. We are reviewing our process for asset-level rankings for operational water-related risks. We recognise that transparent disclosure of water-related risks at an asset level is a part of our Water Stewardship Position Statement commitments and we intend to re-incorporate relevant asset-level disclosures into our FY2026 disclosures.

|

|

Collective action Collaboratively improve regional water policy and governance and shared water challenges within our communities and across our value chain with all stakeholders |

We continued our program of WRSAs in FY2025, releasing an addendum to our Andean aquifers and San Jorge Bay WRSAs in northern Chile. We also released the Hunter Region WRSA, and a CBWT for our NSWEC asset as part of our FY2025 disclosures. |

|

Learn and innovate Proactively share, source, develop and apply knowledge and technology to water management. |

We continued to progress the Groundwater Modelling Decision Support Initiative (GDMSI) with partner organisations, Rio Tinto and Flinders University, to help promote the application of advances in groundwater modelling for environmental and water management decisions.

In response to the mining sector’s growing need for sustainable water management, we launched the Global Water Challenge – an open innovation initiative designed to identify and de-risk breakthrough water treatment technologies. The program reflects our commitment to our 2030 Water Stewardship Vision and broader ambition to improve sustainability outcomes through innovation. Initiated in FY2023 and launched at Expomin in Santiago, Chile, the Challenge attracted 166 applications from 17 countries. Following a rigorous selection process, five innovators were chosen to form the Global Water Cohort – with cohort activities commencing in FY2025. For more information refer to our case study. |

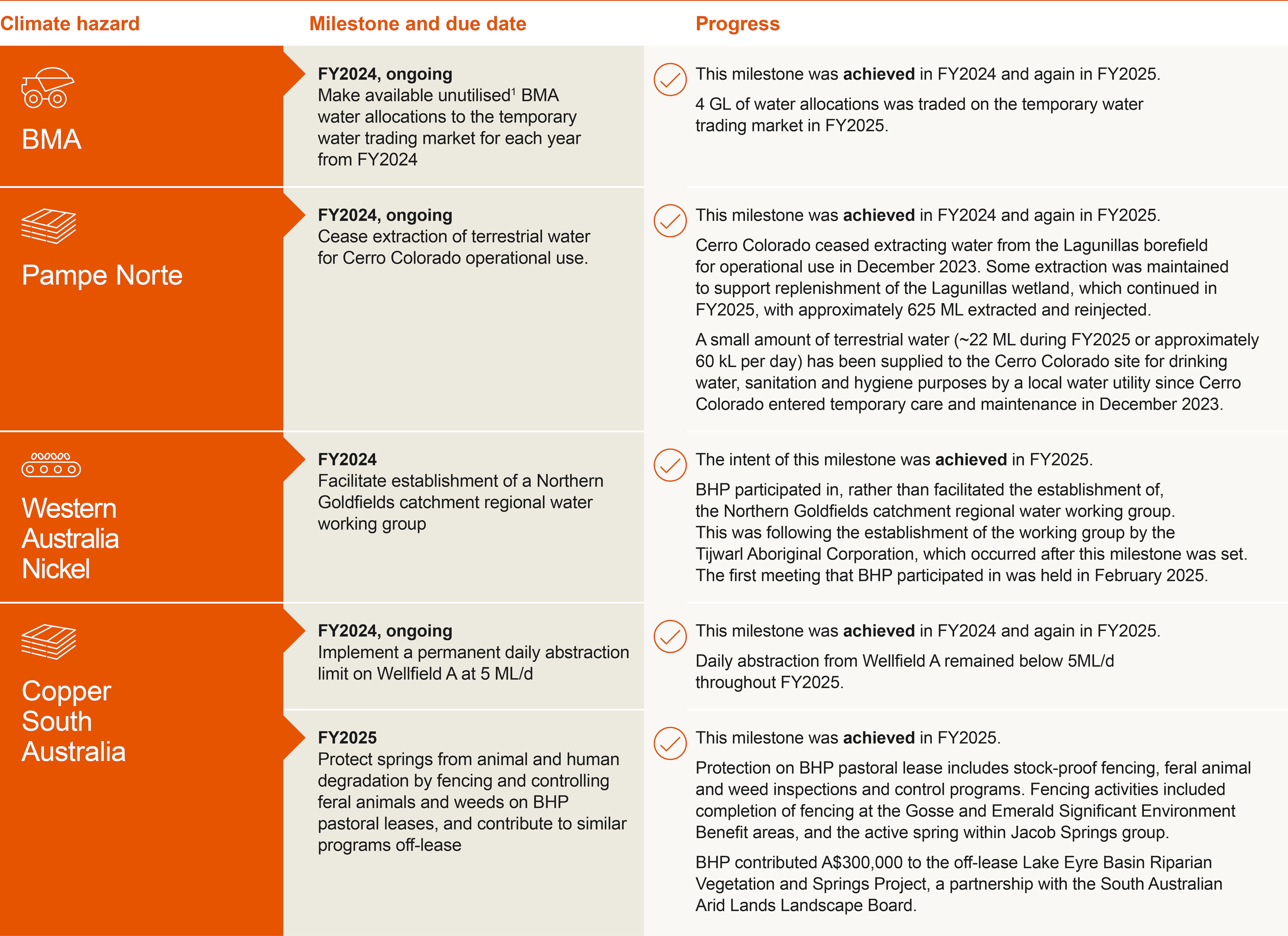

Context-based water targets progress

In our Water Stewardship Position Statement, we committed to develop context-based water targets (CBWTs). In FY2023, as one of our Healthy environment goal short-term milestones, we released our first suite of CBWTs that will apply until the end of FY2030. CBWTs are developed based on water-related risks in the catchment areas and shared water challenges identified through an independent WRSA. The CBWTs aim to improve our water management and contribute to collective benefit and shared approaches to water management in the regions where we operate.

Following the FY2023 release of WRSAs and CBWTs, we added an addendum to our Andean aquifers and San Jorge Bay WRSAs in FY2025 after stakeholder consultations were initially delayed due to social unrest in Chile. This addendum, which reflects the participation of various actors, presents the updated shared challenges and opportunities for collective action for the Altoandina macrozone in the Tarapacá and Antofagasta regions and for San Jorge Bay, all in northern Chile. We also published a WRSA for the Hunter River catchment in New South Wales, Australia, and released a CBWT for NSWEC. The NSWEC CBWT aims to enhance ecosystem connectivity through revegetation and targeted restoration along the Hunter River riparian zones. Additionally, we released a CBWT for the Globe-Miami legacy asset site in Arizona, which aims to improve the sustainability of regional water resources by diverting natural water flows around mine-affected areas. This CBWT was informed by the Cobre Valley Watershed Restoration and Action Plan, a report developed by the Cobre Valley Watershed Partnership with contributions by BHP as a stakeholder. We have now achieved our commitment to develop CBWTs within our operations but may release further CBWTs when appropriate for the operating, environmental and social context.1

We continue to seek opportunities to source our water from lower-grade sources, particularly in water-stressed areas. Both Copper South Australia and Pampa Norte in Chile have CBWTs to materially reduce terrestrial water use. Escondida’s operational water withdrawals have been sourced from desalinated seawater since FY2020.2 Both Escondida and Pampa Norte have a CBWT to improve the water efficiency in mining operations by 10 per cent by FY2030 from a FY2022 baseline, aiming to optimise marine water use.

In some areas, we extract more water than we use through mine dewatering and have set our CBWTs in consideration of this local context. For example, one of WAIO’s CBWTs is ‘at least 50 per cent of WAIO surplus water will be prioritised for beneficial use to improve the sustainability of regional groundwater resources or generate social value’.

For more information on WRSAs and CBWTs, including progress against the targets and longer-term CBWT milestones, refer to our Shared water challenges webpage.

The CBWTs are underpinned by a series of milestones, and we delivered all asset-level CBWT FY2025 short-term milestones, as summarised below.

Footnotes:

1 CBWTs are intended to apply at the asset level for our operated assets. We will review the need to revise or create CBWTs when there are substantial changes to our portfolio or one of our projects moves into the operational phase.

2 Small quantities of groundwater are extracted for pit dewatering and to recover seepage from tailings, to enable safe mining and support environmental control. This water is used for operational consumption.

Progress against FY2025 context-based water target milestones

Footnote:

1 Some water allocations at BMA are not made available for sale ‘in year’ and are retained for strategic contingency purposes as ‘carry over’. Unutilised ‘carry over’ is subject to ongoing assessment throughout the year as to what can be made available. At 30 June, any unused ‘carry over’ amounts are incorporated into the following financial year’s ‘in year’ water for the total river scheme’s announced allocations by the Resource Operator.

Water data

Below is a summary of our FY2025 water balance:

FY2025 Key water data insights:

- Seawater withdrawals remained our largest source, accounting for 52 per cent of total withdrawals at 221,860 megalitres (ML), similar to 223,440 ML in FY2024.

- Low-quality water (Type 3) made up 62 per cent of total withdrawals, with volumes stable at 266,920 ML, compared to 269,460 ML in FY2024.

- Freshwater withdrawals (Type 1 and 2) increased by 46 per cent, rising from 111,120 ML in FY2024 to 162,740 ML in FY2025, primarily due to increased rainfall and runoff at BMA.

- Water withdrawals in water-stressed areas decreased from 33,450 ML in FY2024 to 31,830 ML in FY2025, largely due to the cessation of terrestrial groundwater extraction at Cerro Colorado in December 2023.

- Water discharges rose by 15 per cent, from 128,100 ML in FY2024 to 147,510 ML in FY2025, driven by increased surface water discharge at BMA following significant rainfall.

- Recycled and reused water volumes at Pampa Norte declined significantly due to a further refinement of the calculation methodology and shift from estimated to measured data in one of the flows.

This section provides detailed disclosure of our various water metrics in line with the ICMM guidance, GRI sustainability reporting Standards and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) Standards. To allow year-on-year comparison with FY2025 BHP operated assets, the water performance data presented here excludes water data from the following discontinued operations: BMC (sold on 3 May 2022), Blackwater and Daunia (sold on 2 April 2024); and assets in BHP's Petroleum business (merged with Woodside on 1 June 2022) to ensure ongoing comparability of performance. All water data currently excludes Carrapateena and Prominent Hill from Copper South Australia. FY2021–FY2024 water data excludes West Musgrave. Data is intended to be reported for Carrapateena and Prominent Hill from FY2026 once water accounts have been aligned with ICMM guidance and MCA’s WAF. We intend to align Prominent Hill and Carrapateena to ICMM guidance and the MCA’s WAF to enable disclosure of water data from these operations from FY2026. Definitions of water metrics, sources, types and detailed water data by asset are provided in the BHP ESG Standards and Databook 2025, in the BHP Annual Report 2025 – Additional information 10.4 and in the ICMM Guidance and WAF. We have presented data from FY2021 to provide a five-year trend. Data has been rounded to the nearest 10 megalitres to be consistent with asset/regional water information on this webpage and within the BHP Annual Report 2025. In some instances, the sum of totals for quality, source and destination may differ due to rounding.

Since FY2021, BHP has used the WWF Water Risk Filter to describe basin risk for our operated assets as discussed on this webpage under BHP basin risk. Using the WWF Water Risk Filter, no operated assets were classified as having high water stress. We have chosen to maintain two of our operated assets (Pampa Norte and legacy assets (United States)) as classified as having high water stress, as per our FY2024 reporting. We intend to review our use of the WWF Water Risk Filter in FY2026. The data for these water-stressed assets are shown in the BHP ESG Standards and Databook 2025.

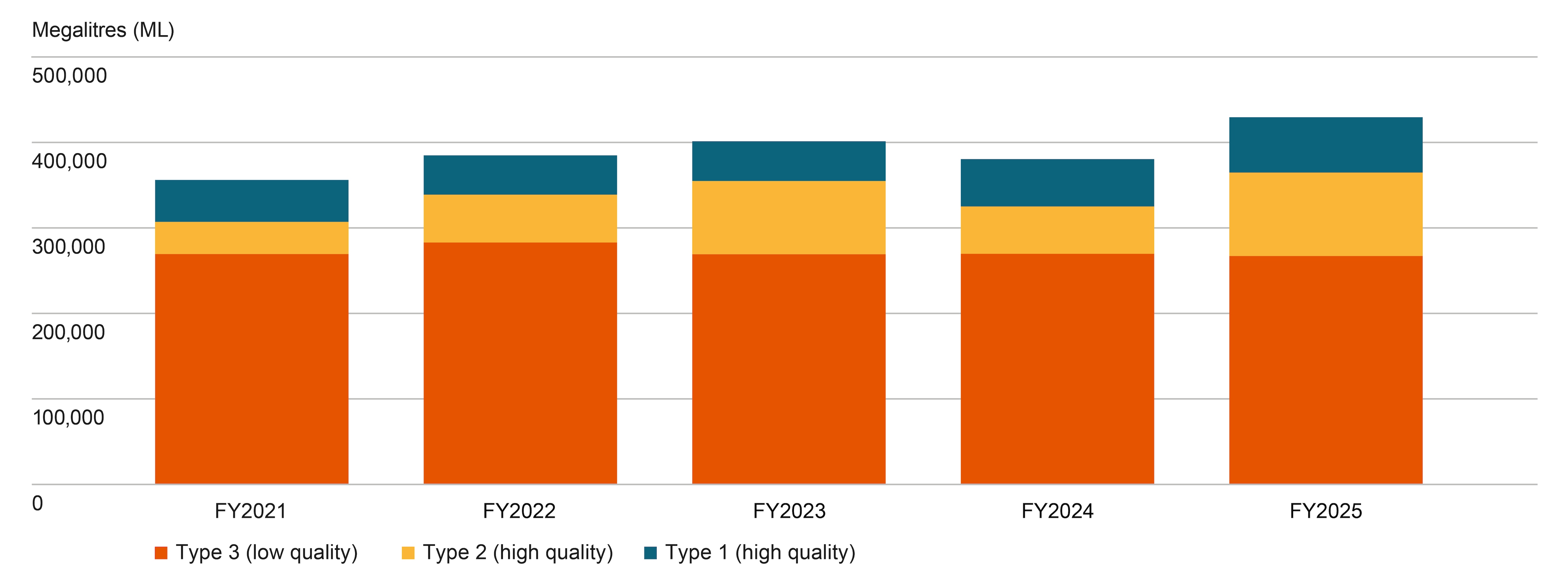

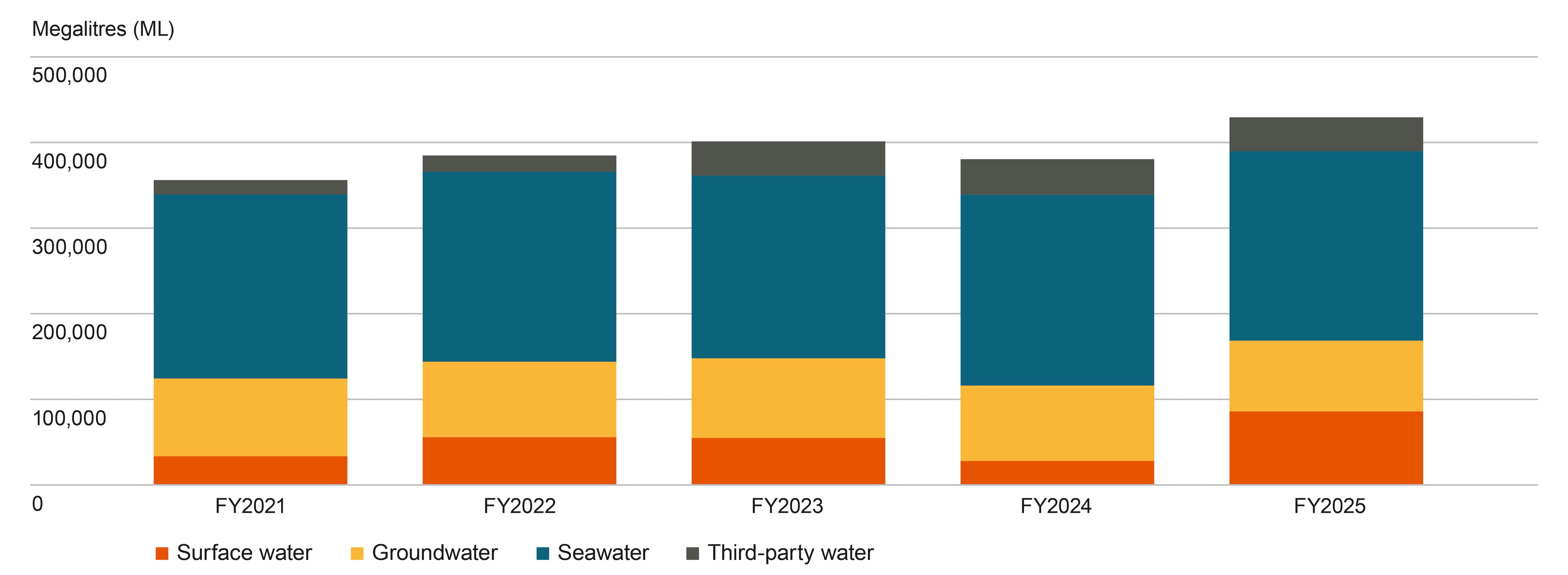

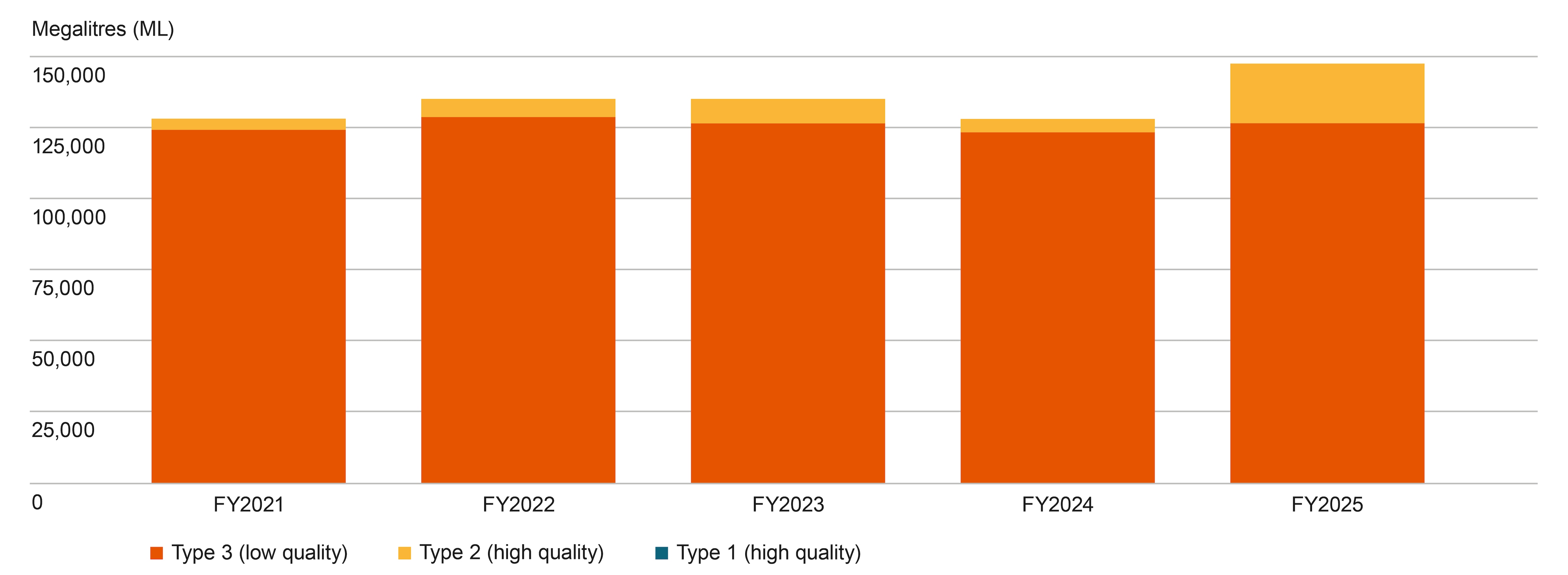

Water withdrawals

Water withdrawals represent the volume of water, in megalitres (ML) received and intended for use by the operated asset from the water environment and/or a third-party supplier.

FY2021–FY2025 Total withdrawals (by quality)1

Footnote:

1. Water quality type as defined in the BHP ESG Standards and Databook 2025.

FY2021–FY2025 Total withdrawals (by source)1

Footnote:

1 As defined by the MCA’s WAF User Guide V2.

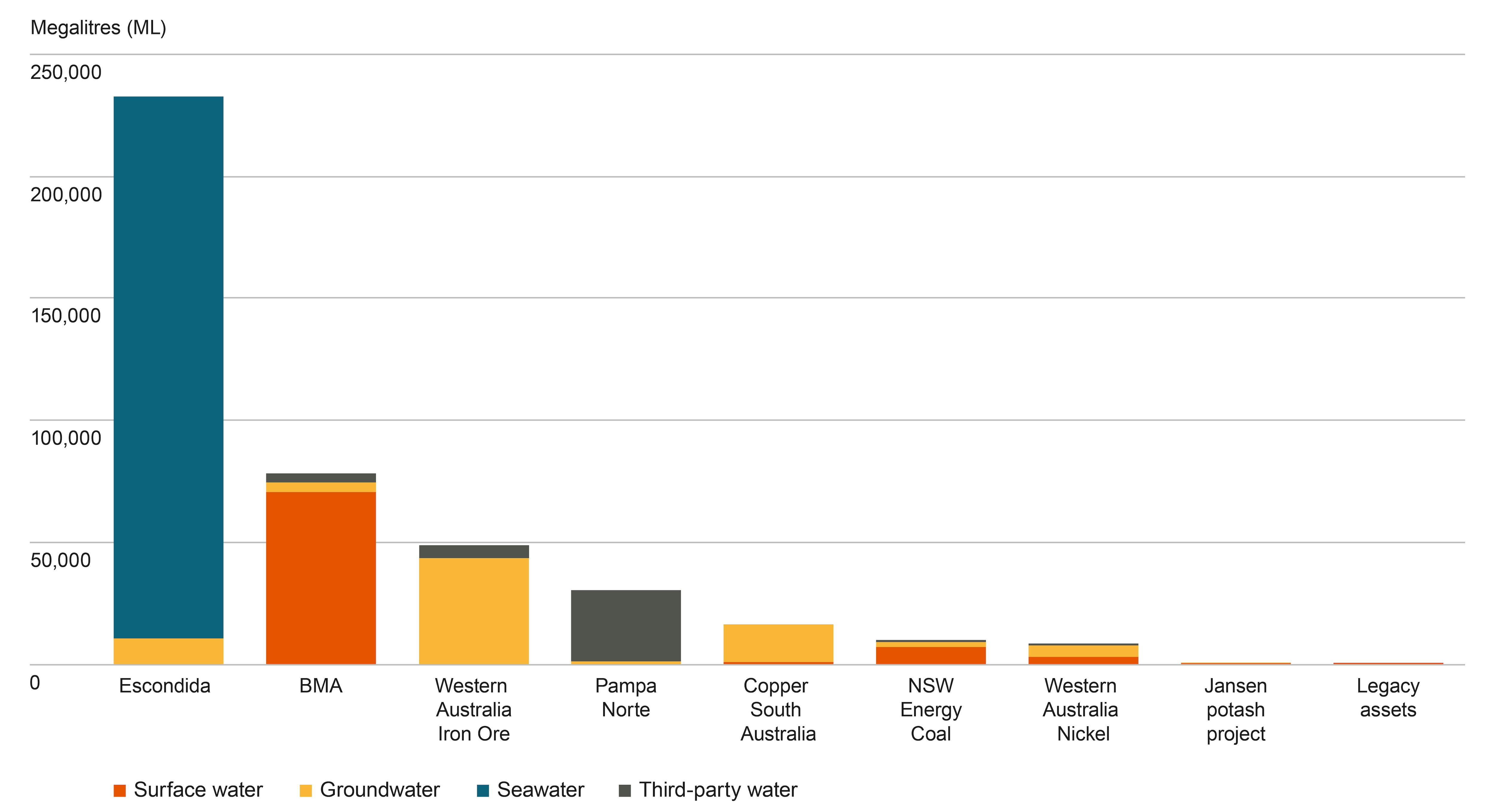

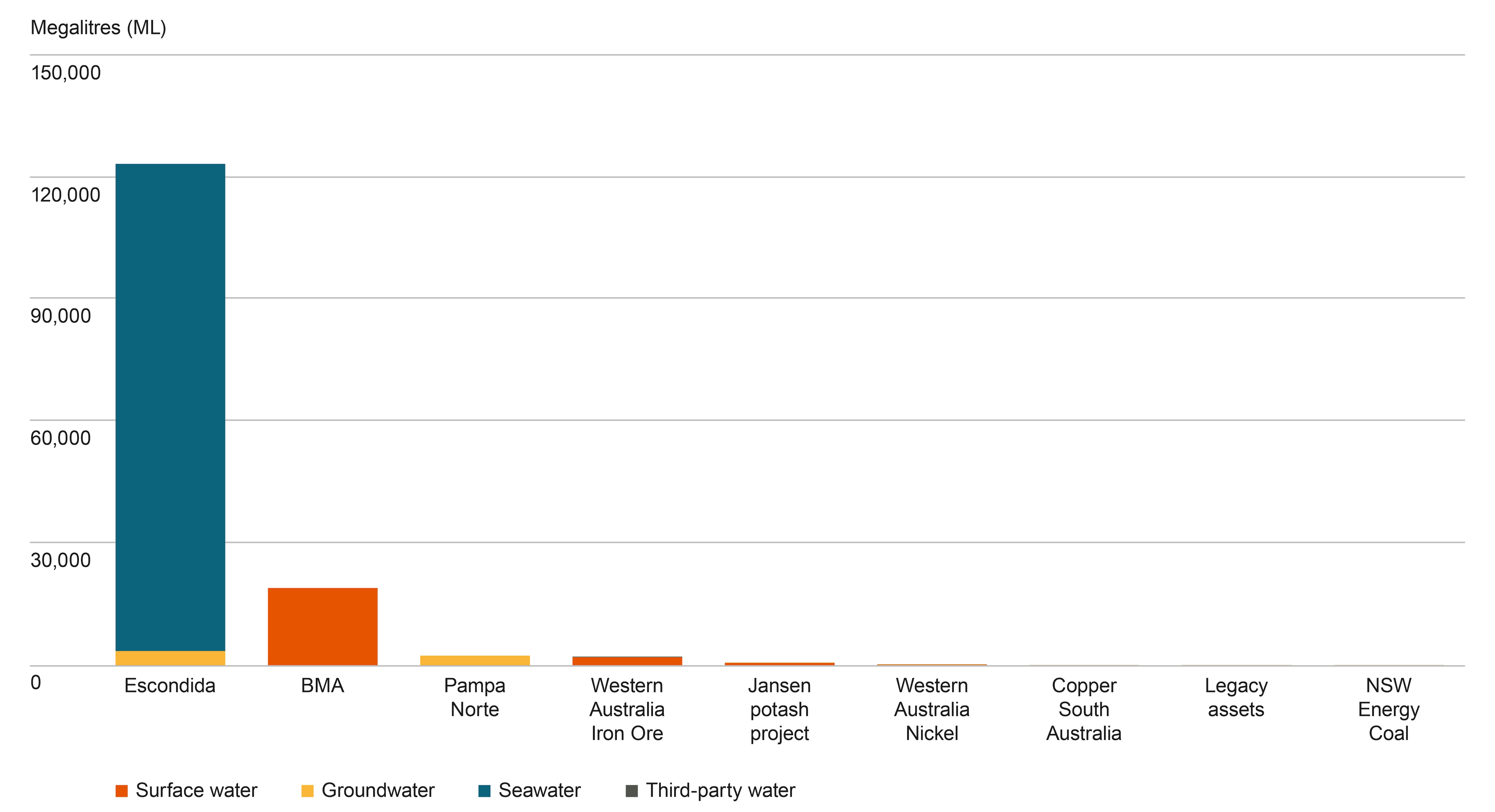

FY2025 Withdrawals by operated assets (by source)1

Footnote:

1 As defined by the MCA Minerals Industry WAF User Guide V2.

In FY2025, approximately 62 per cent of our water withdrawals consisted of water classified as low quality by ICMM definition.

Water withdrawals for FY2025 across our operated assets increased by 13 per cent from FY2024 (from 380,580 ML to 429,660 ML).

Our withdrawal of high-quality water (Type 1 and Type 2) increased by 46 per cent from 111,120 ML in FY2024 to 162,740 ML in FY2025 and the proportion of high-quality water as a proportion of total withdrawals was 38 per cent, compared to 29 per cent in FY2024. This was primarily due to an increase in Type 1 and 2 surface water (precipitation and runoff) withdrawal from BMA, attributable to significant rainfall (i.e. not due to changes in consumption or recycling/re-use).

Total water withdrawals from operated assets located in high or very high water-stressed areas (as determined by manual adjustment of the WWF Water Risk Filter to include Pampa Norte and legacy assets as per FY2024) were 31,830 ML (7 per cent of total withdrawals for BHP operated assets) compared to 33,450 ML (and 9 per cent) in FY2024; and consisted of 84 per cent high-quality (Type 1 and 2) water compared to 81 per cent in FY2024. This is primarily due to cessation of terrestrial groundwater extraction (Type 3) for operational use at Cerro Colorado, since December 2023 when Cerro Colorado entered temporary care and maintenance. This is in line with Pampa Norte’s CBWT FY2024 milestones to cease extraction of terrestrial water for Cerro Colorado operational use.

The majority of our water withdrawals (approximately 52 per cent) came from seawater, with absolute withdrawals sourced from seawater remaining stable – 221,860 ML in FY2025 compared to 223,440 ML in FY2024. Currently, most of Escondida’s and Pampa Norte’s operational water consumption is met by desalinated seawater water (via third parties for Pampa Norte), and some of the third-party water for Western Australia Nickel is sourced from desalinated seawater. Absolute withdrawals from groundwater also remained relatively stable – 82,820 ML in FY2025 for direct groundwater withdrawal compared to 88,270 ML in FY2024, and 39,790 ML in FY2025 for third-party groundwater withdrawal compared to 41,640 ML in FY2024. Withdrawals from surface water have significantly increased. These contributed approximately 20 per cent (85,190 ML) of withdrawals in FY2025, compared to 7 per cent (27,230 ML) in FY2024. This is primarily due to increased surface water withdrawal from our BMA and NSWEC assets attributable to significant increase in rainfall. In FY2025, BMA accounted for approximately 83 per cent of surface water withdrawal across our operated assets and NSWEC approximately 9 per cent. In FY2025, WAIO accounted for approximately 53 per cent of groundwater withdrawal across our operated assets. There was an absolute reduction in withdrawals relating to groundwater of over 5,400 GL. This is primarily associated with WAN going into temporary suspension, and Cerro Colorado going into temporary care and maintenance and ceasing groundwater extraction for operational use, in accordance with Pampa Norte’s CBWT FY2024 milestone.

The withdrawals and the material contributors to these were within expectations for FY2025. Withdrawals from surface water (including precipitation and runoff) is influenced by climatic conditions, such as rainfall and occurrence of extreme weather events, and therefore is subject to higher variability and is less predictable. Water management practices at our operated assets where this may occur are designed to accommodate this variability. Therefore, the occurrence of such events is not anticipated to affect our current management activities and strategy or result in elevated exposure to risk.

The availability of water for multiple uses was identified through the WRSAs as a shared water challenge in the majority of the regions where we operate. To address this challenge, some of our operated assets have released CBWTs that may assist in reducing our withdrawal of water from the environment or increase water supplied from low-quality sources (such as seawater) by either increasing efficiency of water used for operational purposes, maximising return of surplus water (without use) to the environment (called ‘Other managed water’ by the ICMM Guidance) or share/return our licensed water allocations to others. For example, at BMA we have a target to support water stress reduction in the Fitzroy Basin through better use of water in our operations.

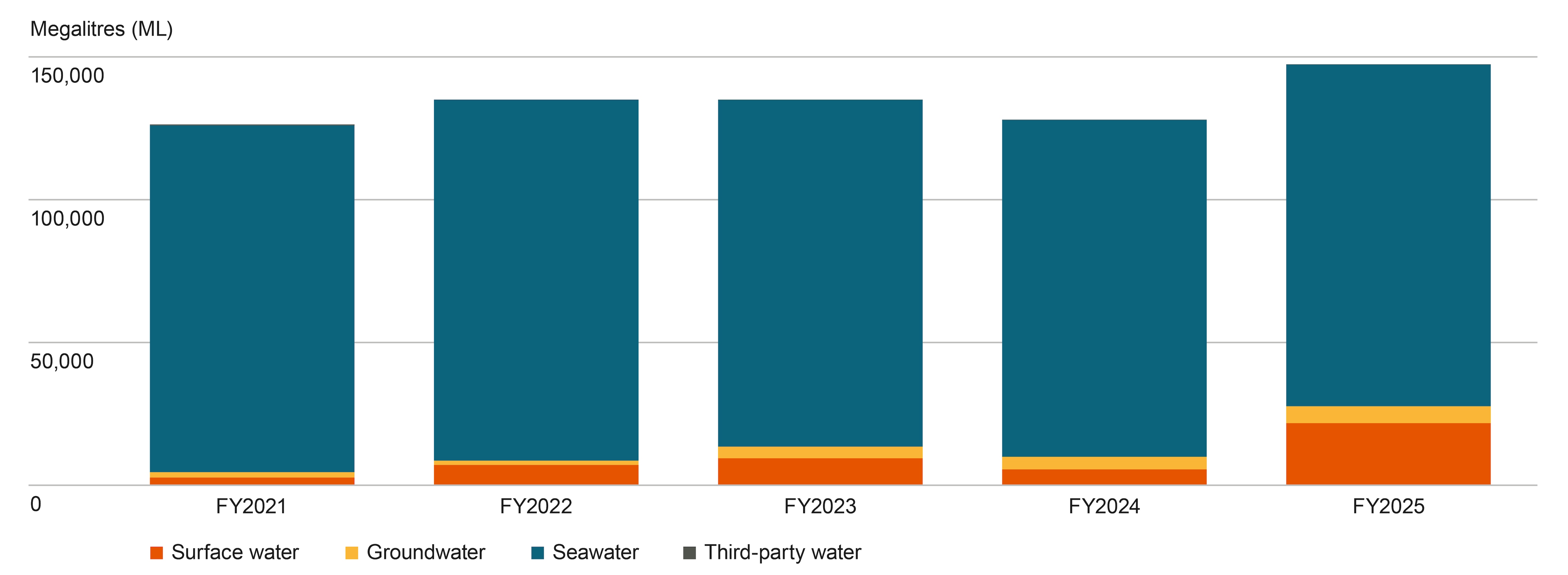

Water discharges

Water discharge includes water that has been removed from the operated asset and returned to the environment or distributed to a third party. This includes seepage from tailings storage facilities to groundwater, discharge from operations to surface waters (which are also affected by periods of higher rainfall) and discharge to seawater. Water we treat and then on-supply to third parties is captured as diverted water consistent with the ICMM guidance as it is not intended for operational purposes.

FY2021–FY2025 Total discharges (by quality)1

Footnote:

1 Water quality type as defined in the BHP ESG Standards and Databook 2025.

FY2021–FY2025 Total discharges (by destination)1

Footnote:

1 As defined by the MCA Minerals Industry WAF User Guide V2.

FY2025 Discharges by operated asset (by destination)1

Footnote:

1 As defined by the MCA Minerals Industry WAF User Guide V2.

Total water discharges for FY2025 were 147,510 ML, a 15 per cent increase from 128,100 ML in FY2024. Total water discharge in water-stressed areas was 2,340 ML, 100 per cent of which was Type 3/low-quality water. 14 per cent of our discharges are comprised of high-quality water (all Type 2), compared to 4 per cent in FY2024.

Around 81 per cent of global water discharge from BHP’s operated assets is Type 3 discharge to seawater from our desalination activities at Escondida, down from 92 per cent in FY2024. This discharge is the biproduct of reverse osmosis of seawater. The absolute volume discharge has not changed significantly from FY2024, with an increase of close to 1,690 ML. Our Escondida asset’s discharges are to seawater and regulated under government-issued permits that include discharge limits.

BMA has had an increase of approximately 644 per cent in Type 2 surface water discharge since FY2024, increasing from 2,550 to 18,980 ML, and contributing 13 per cent of total discharges from BHP’s operated assets in FY2025. BMA undertakes discharges of mine-affected water regulated under government-issued permits that include discharge limits and specify particular conditions when discharge is permitted, associated with upstream and downstream creek flow, and discharge water quality. Following significant rainfall, BMA undertook discharge activities, including taking the opportunity to release water stored from previous years. BMA received three fines in FY2025 in relation to the discharge of mine-affected water. For more information refer to the Water-related legal performance section below. Other sites that have water discharges are shown in the Water performance section and in the BHP ESG Standards and Databook 2025. None of our operated assets discharge untreated effluent from wastewater treatment plants to any water streams.

Discharge to surface water (usually riverine systems) is influenced by climatic conditions, such as rainfall and occurrence of extreme weather events, and therefore is subject to higher variability and is less predictable. Water management practices at our operated assets where this may occur are designed to accommodate this variability, using Trigger Action Response Plans. Therefore, the occurrence of such events is not anticipated to affect our current management activities and strategy or result in elevated exposure to risk.

In FY2025, 33 per cent of our operated assets (the same value as FY2024) did not discharge water as their water was either consumed in operational activities or reused/recycled.

Water recycled/reused

The ICMM guidance defines reused water as water that has previously been used at the operated asset that is used again without further treatment, and recycled water is water that is reused but is treated before it is used again.

The amount of water reused or recycled decreased by 24 per cent from 242,800 ML to 185,560 ML. This was due to the temporary closure of operations at Western Australia Nickel and Cerro Colorado, and a change in methodology at Spence (where water recirculated during heap leaching was previously included as reuse).

During FY2025, the total volume of water recycled/reused at water-stressed assets was 97,070 ML, down approximately 41 per cent compared to FY2024. However, the amount of recycled and reused to total withdrawals remained high at 305 per cent, although lower than 496 per cent in FY2024. This decrease is associated with Pampa Norte, as outlined above.

Although not as material, increases in water reuse and recycling were recorded at several other assets:

- WAIO Port: higher recycled process water use, due to increased fines handling and throughput

- NSWEC: improved data capture, reduced surface water (river) water extraction and commissioning of a flocculation plant boosted reliance on recycled water

- BMA: apparent increase reflects enhanced data collection, not actual change in reuse or recycling.

Other managed water

Other managed water (previously called diverted water) is water that is actively managed by an operated asset but not used for any operational purposes. For example, we withdraw water and treat it for use as drinking water by local communities, such as in the town of Roxby Downs in South Australia. In FY2025, 97,510 ML of water was withdrawn without any intention to be used at BHP operated assets, up approximately 19 per cent from 82,090 ML in FY2024. This increase was predominantly driven by an increase in Type 2 surface water diversion at our BMA asset, associated with heavy rainfall in the region during the reporting period. An increase in WAIO Type 1 groundwater diversion also contributed, with the increase attributed to higher dewatering activity, with new bores coming online and contributing to greater discharge volumes into surplus water systems. This relates to WAIO’s CBWT. More information can be found at the Shared water challenges webpage and in the WAIO water case study.

Water-stressed areas reported 34,060 ML of other managed water withdrawals, down 10 per cent compared to 37,870 in FY2024. As in FY2024, approximately 50 per cent of the other managed water is Type 1. In water-stressed areas, 27 per cent was high quality (all Type 2). The decrease in these withdrawals was predominantly driven by the re-establishment of flow control at artesian wells following power supply outages, as well as a reduction in on-site project activity that had previously increased well water usage in FY2024 at one of our legacy assets sites. Note: the other managed water withdrawal at this site is diverted to riparian habitat, including the higher volumes withdrawn in FY2024.

As the withdrawal of other managed water may occur in a different reporting period to its discharge, in any given annual period there may be a differential between withdrawal and discharge volumes for other managed water. In FY2025, we discharged 60,860 ML of other managed water.

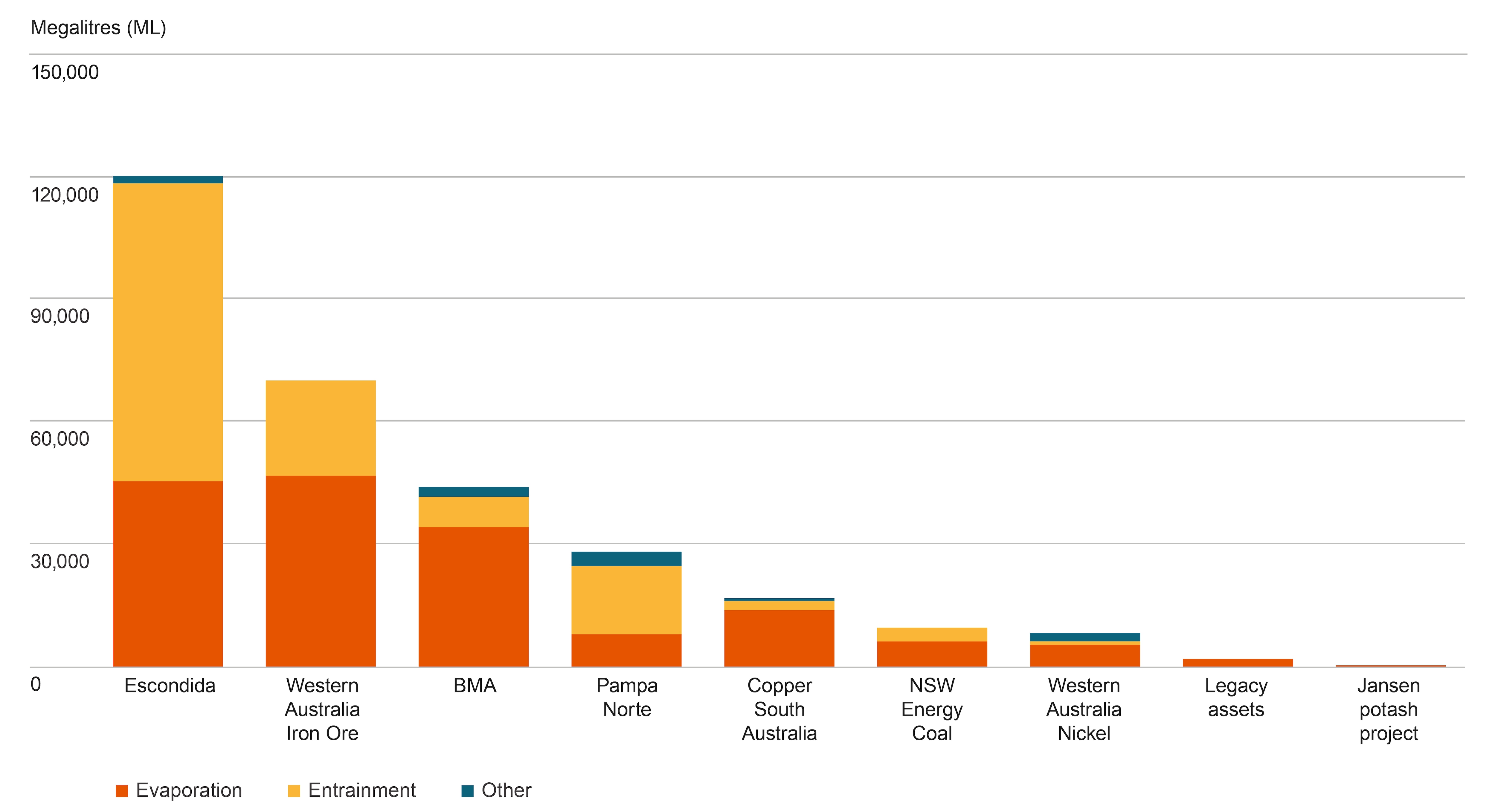

Water consumption

In FY2025, evaporation and entrainment remained the most significant contributors to consumption. Evaporation occurs during a number of operational activities, including dust suppression, storage of tailings and storage of water.

Evaporation consumption is inherently linked with climatic conditions. Evaporation data is estimated or simulated using average climatic conditions and therefore consumption due to evaporation should remain relatively stable. Due to the link with climatic conditions, the volumes consumed via evaporation are partly outside of BHP’s direct control, although we do control how much water is directed to evaporation locations.

Entrained water includes water incorporated into product and/or waste streams, such as tailings, that cannot be easily recovered. Entrainment may show variability due to the type and location of ore during any given reporting period. The use of water in our processing facilities or for reducing dust release during storage of product can result in entrainment of water.

The category of ‘other’ for consumption includes several uses, the most significant being water used by people for drinking or ablutions at operated assets.

The collation and disclosure of consumption will assist in identifying areas for improvement in data accuracy for entrainment and evaporation, and assist with identifying opportunities to reduce, where possible, loss of water.

Total water consumption in FY2025 was 299,540 ML compared to 292,170 ML in FY2024. Consumption in water-stressed locations was 30,090 ML (10 per cent of overall water consumption for BHP operated assets) compared to 27,500 ML in FY2024. This increase in consumption at water-stressed locations is primarily driven by change in the Pampa Norte WAF model. The flow associated with the concentrator was not reported in FY2024, as it was then treated as an imbalance between water inputs and outputs. The operated assets in FY2025 that consumed the most water were Escondida, WAIO and BMA. Entrainment of water in tailings is the largest contributor to consumption at Escondida, although consumption via evaporation did increase in FY2025 compared to FY2024 due to greater tailings distribution associated with higher production. Evaporation is the key driver of consumption at WAIO and BMA, mainly via evaporation from dust suppression, tailings and water storage. It should be noted that in any given reporting period, consumption and discharge volumes might be higher than withdrawals as evaporation can occur from water that has been captured and stored during previous periods.

FY2025 Consumption by operated asset

Changes in water storage

The ICMM guidance recommends reporting of changes in water storage for clarity, as an indicator of internal water dynamics and to provide increased transparency of all elements of a water balance. More information can be found in this guidance.

As expected, the largest changes in water storage during FY2025 occurred at our BMA operated assets. This is where the majority of our water source is from rainfall and, is highly variable year to year. While BMA recorded an increase in discharges in FY2025 following significant rainfall, storages have also continued to increase.

Water-related legal performance

During FY2025, we had three incidents of water-related non-compliance that resulted in a formal enforcement action, all at BMA in Australia. One of the fines at BMA was associated with unauthorised releases of mine-affected water, and the other with not monitoring the discharge of mine-affected water as required. Two more environment fines were incurred from a single event during FY2025 associated with another unauthorised release of mine-affected water. This event is recorded in FY2025 reporting, although the fines were paid in July 2025 (FY2026). These events have been investigated and corrective actions have been identified and are being implemented.

Also in FY2025, we paid a fine of approximately US$8 million to the Chilean Environmental Regulator (SMA) and settled two related environmental damages claims at Escondida in Chile related to Escondida’s extraction of water from the Monturaqui aquifer.

For more information refer to the BHP ESG Standards and Databook 2025, the BHP Annual Report 2025, Operating and Financial Review 9.9 – Nature and environmental performance and the BHP Annual Report 2025 – Directors’ Report, section 13.

Risk

BHP’s portfolio of long-life operated assets means we must think about the long term, plan in terms of decades and consider the needs and circumstances of future generations. We need to consider our operated assets’ needs and the potential for regional changes to water resources due to climate change, pollution, population growth and changing expectations.

The shared nature of water resources means we also need to think ‘beyond the fence’, which includes the interactions within catchments (a term used interchangeably with ‘basins’ on this webpage) when managing risk. As part of our Risk Framework, our operated assets are required to identify, assess and manage the water-related risks associated with their activities and make strategic business decisions in line risk appetite.

We will continue to review our water-related risk profile in line with our mandatory minimum performance requirements for risk management. For more information, refer to the BHP Annual Report 2025, Operating and Financial Review 7 – How we manage risk.

The management of water-related risks needs to reflect the different physical environments, hydrological systems and socio-political and regulatory contexts in which we work. BHP must take into account the interactions that we and external parties have with water resources within catchments, shared marine regions and groundwater systems. In our disclosure of water-related risk, we present two facets of risk:

- operational water-related risks (threats or opportunities to BHP’s business, water resource, communities or the environment that are related to BHP activities at our operated assets)

- basin risks (threats or opportunities associated with inherent basin characteristics in areas where BHP operates, such as drought or flooding etc.), termed ‘inherent risk’ within the ICMM guidance

These two facets of risk seek to consider shared water challenges within the catchment and how catchment risk may influence company risks.

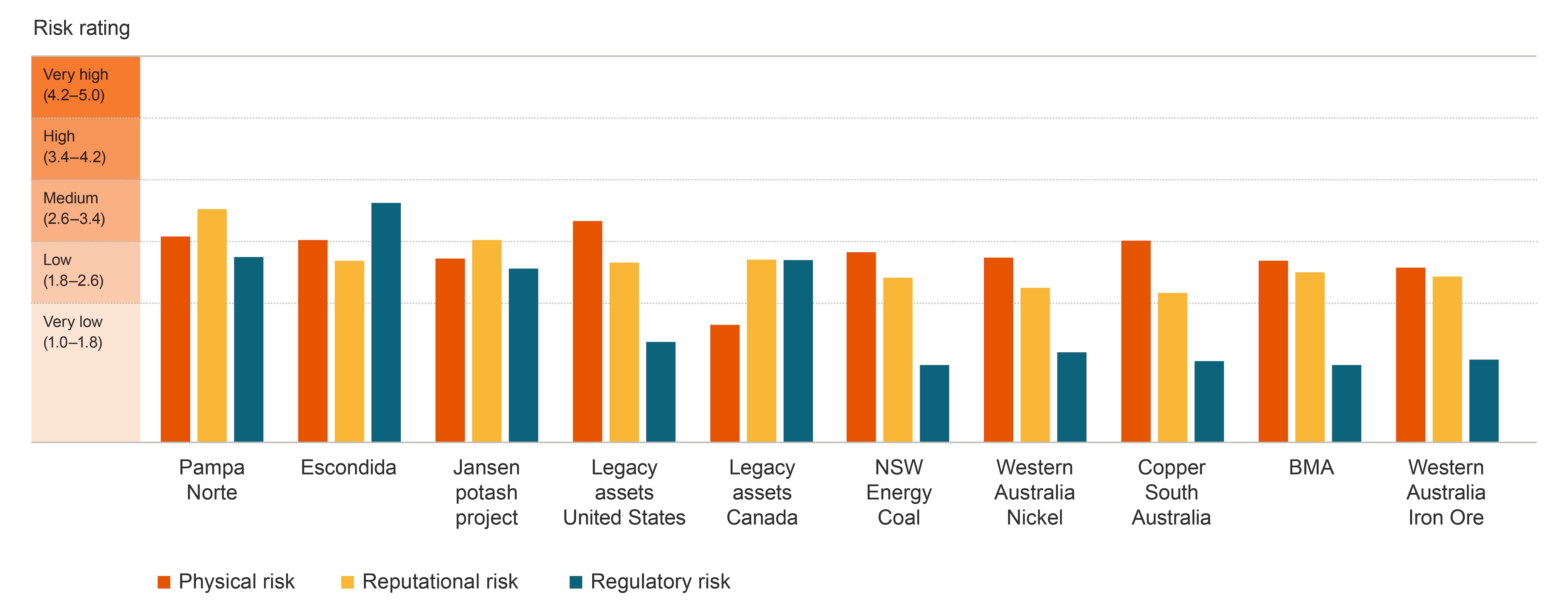

BHP and basin risk

We use the WWF’s Water Risk Filter to assess the level of basin risk of each of the locations where we have operated assets. We use the level of basin risk as an input to assessments of our operational water-related risks; usually as a causal factor and when determining the severity of potential impacts and likelihood of the risk event occurring.

The WWF Water Risk Filter assesses the level of risk in the basin based on the location of the basin from physical, regulatory and reputational perspectives using global (or local where available) datasets of 32 basin risk indicators. Other external water guidance (e.g. the CEO Water Mandate) also classify risk using these three categories.

For some of our operated assets, such as our BMA, WAIO and North American legacy assets, there are multiple individual sites within the asset that are geographically spread. For these, multiple locations across the geographical spread were assessed in the WWF Water Risk Filter and the average overall basin risk of the locations reported for the operated asset.

The WWF Water Risk Filter methodology allows for the use of local knowledge to verify basin risk outcomes and is supported by other external water disclosure frameworks, such as the CEO Water Mandate and the CDP.

Although we have presented the level of basin risk in accordance with the outcomes from the WWF Water Risk Filter in our tables and figures, the discussion below indicates where, based on our local knowledge, we consider the outputs of the WWF Water Risk Filter may be under- or over-estimating basin risk.

In the majority of locations where we operate, BHP considers regulatory risk for the basin as higher than the WWF Water Risk Filter due to knowledge of specific regulatory requirements applicable to each operated asset and other operators in the region, regional policy, plans and constraints and current discussions with local and national regulators regarding water permitting and performance for the operated asset and the region. We have incorporated our local knowledge of regulatory risk within our assessment of severity and likelihood in our operational water-related risk assessments.

Other risks that we consider higher than under the WWF Water Risk Filter include physical risk for Olympic Dam due to the use of Great Artesian Basin water resource, which supports important springs and is an important shared water resource in the region, and reputational risk at our Chilean operated assets (Escondida and Pampa Norte), a legacy asset in the United States and WAIO, due to community and media interest in these regions. These higher basin risks have been incorporated into the relevant operational water-related risk assessment (e.g. catchment risk assessment for Olympic Dam).

Refer to the graphics below for a summary of our basin risk level due to location for each operated asset and the catchment where they are located.

Basin risk by type (WWF water risk filter)

Basin characteristics

The following table provides further characteristics of the basins, reflecting the outcomes from the WWF Water Risk Filter, where BHP operated in FY2025. This includes the river basin names, climatic conditions and basin physical risk. In addition, it provides information regarding the key water source, water activities and water consumptive uses of the water resources for each of our operated assets and information regarding discharge permitting. Note that due to the nature of our operations, our activities do not necessarily impact the river basin named in the table below because river water is not necessarily our water source. For example, the WWF Water Risk Filter shows Olympic Dam as being in the Lake Gardiner River basin, but our operations do not interact with or access river water, as our key water source for Olympic Dam is groundwater sourced from the Great Artesian Basin.

The basin physical risk level from the WWF Water Risk Filter is presented in this table to indicate whether BHP’s operated assets are in a ‘water-stressed area’. Operated assets with a physical risk rating of high or above, as assessed for the FY2025 period, are deemed to be in areas of water stress. However, this year no operated assets triggered this threshold, so BHP has determined to maintain FY2024 results for this year’s reporting (Pampa Norte and an individual legacy asset site in the United States) and intends to review the suitability of the WWF Water Risk Filter in FY2026. In line with the ICMM guidance and other frameworks (e.g. GRI/SASB), we have disclosed the proportion of our water withdrawal, discharge and consumption that occurs in water-stressed areas in the water performance section on this webpage.

Characteristics of basins where BHP's operated assets were located in FY2025

| Asset (main commodity) | River basin1,2 | Climatic conditions | Physical risk (WWF) | Main operational water source, activities and consumption | Discharge (Y/N), Discharge quality limit type |

| Escondida (copper) | Puna de Atacama Plateau | Arid or semi-arid | Medium | Seawater – open-pit mining and mineral processing, entrainment in tailings | Y, Regulatory and management controls |

| Legacy assets – Canada (closed sites) | Huron Bay, Hudson Bay, North Atlantic, North Pacific | Moderate precipitation | Very Low | Surface water (limited operational water predominately recovery for treatment) – water treatment, tailings management, evaporation | N, N/A |

| Legacy assets – United States (closed sites) | Colorado, North Pacific and Rio Grande | Arid or semi-arid | Medium (BHP has chosen to maintain FY2025 treatment as High) |

Surface water (limited operational water predominately recovery for treatment) – water treatment, tailings management, evaporation | N, N/A |

| Western Australia Nickel (nickel) | Western Plateau (Salt Lake) | Arid or semi-arid | Low | Groundwater – minerals processing, dust suppression, tailings management, evaporation | Y, Regulatory |

| New South Wales Energy Coal (thermal coal) | Australia (Hunter) | Moderate precipitation with distinct dry season | Low | Surface water – minerals processing, dust suppression, evaporation/entrainment | N, N/A |

| Copper SA (copper) | Australia (Lake Gardiner) | Arid or semi-arid | Medium | Groundwater – minerals processing, tailings management, evaporation | N, N/A |

| Pampa Norte (copper) | South Pacific1 | Arid or semi-arid | Medium (BHP has chosen to maintain FY2025 treatment as High) |

Sea, ground and surface water – minerals processing, evaporation | N, N/A |

| Jansen potash project (potash) | Nelson and Saskatchewan1 | Moderate Precipitation | Low | Surface water – minerals processing, evaporation | Y, Regulatory |

| Queensland Coal (BMA) (metallurgical coal) | Australia (Fitzroy2) | Sub-tropical – Moderate precipitation with frequent major storm events | Low | Surface water – minerals processing, dust suppression, evaporation | Y, Regulatory |

| WAIO (iron ore) | Australia (Fortescue2) | Arid or semi-arid | Low | Groundwater – minerals processing, dust suppression, dewatering, evaporation/entrainment | Y, Regulatory |

Footnotes

1 These river basins, as determined by the WWF Water Risk Filter, vary from those previously reported as ‘catchments’. This is because the BHP bespoke tool defines the catchment based on the predominant water source (e.g. groundwater basin rather than river/surface water basin).

2 The WWF Water Risk Filter did not delineate river basins within Australia. The Australian Bureau of Meteorology river basin map was used to provide more granularity on river basins at our BHP operated assets.

Our operational water-related risks

Operational risks are those that have their origin inside BHP or occur because of our activities. Operational water-related risks refer to the ways in which water-related activities can potentially impact our business viability, water resource sustainability or the achievement of our operational and strategic objectives. Our operational water-related activities and risks are influenced by or can influence both the basin and regional scale risks as described above. We prioritise the allocation of water-related risk management resources based on where we believe there is an increased likelihood of potential adverse water-related impacts due to the nature of our activities (e.g. tailings and marine risks).

BHP’s Risk Framework, our Environment Global Standard, and internal water management standard govern the identification, assessment and management of operational water-related risks. More information is contained in the table below. The basin risk discussed above also seeks to inform the assessment of operational water-related risks, usually as a cause of a risk event. For example, high water scarcity within the basin may be a cause for the risk of inadequate water supply, or inadequate flood management may be a cause for an extreme weather impact. Basin risk may also influence the severity of potential impacts and likelihood of the operational water-related risk event occurring. For example, a high basin risk for ecosystem services may increase severity of potential impacts to environmental receptors, such as groundwater-dependent vegetation, if the water resource is not managed appropriately. For more information on our approach to risk management refer to the BHP Annual Report 2025, Operating and Financial Review 7 – How we manage risk.

Unmanaged or uncontrolled operational water-related risks have the potential to adversely impact:

- the health and safety of our employees, contractors and community members

- spiritual and cultural values

- communities, including social and economic viability

- environmental resources, including water, land and biodiversity

- legal rights and regulatory compliance

- reputation, investment attractiveness or social value proposition

- production, growth and development (including exploration)

- financial performance

As discussed above, external water risk disclosure frameworks usually classify risks based on three categories: physical, reputational and regulatory, which is based on the nature of the impact of an event. We classify all identified risks to which BHP is exposed using our Group Risk Architecture and consider physical, reputational and regulatory impacts across each of our risk categories. For more information on our approach to risk classification refer to the BHP Annual Report 2025 Operating and Financial Review 7 – How we manage risk.

The BHP Annual Report 2025, Operating and Financial Review 11 – Risk factors outlines some of the threats and opportunities that may occur as a result of our activities globally. This provides information about some potential water-related threats, such as operational events and significant social or environmental impacts. The information on this webpage expands on this and outlines the current level of operational water-related risks at each operated asset.

The water risk table summarises the operational water-related risks that we have identified across our operated assets. Generally, the majority of our operational water-related risks monitoring relates to water scarcity (not having enough water for our operations or communities), water surplus (having too much water at our operations) or having a potentially unacceptable change to the environment or community from BHP’s water activities.

We are reviewing our process for asset-level rankings for operational water-related risks. We recognise that transparent disclosure of water-related risks at an asset level is a part of our Water Stewardship Position Statement commitments and we intend to re-incorporate relevant asset-level disclosures into our FY2026 disclosures.

The water risk table provides more details about BHP’s operational water-related risks that we have identified, potential impacts and how we seek to proactively manage such risks. We consider how to avoid, minimise or mitigate potential or actual adverse impacts, or enable or enhance positive impacts, including to the environment and community (including cultural and spiritual values), health and safety and our financial performance and reputation. Under our mandatory minimum performance requirements for risk management, material risks are required to be reviewed periodically to evaluate performance.

Water risk table

| Scope | Potential impacts | Management | |

| Catchment | Risk associated with the potential alteration or modification of water catchments or resources in or around the areas where we operate. The risk may be posed by our current or historical activities or those of other water users, or cumulative and indirect impacts to shared water resources. BHP acknowledges and seeks to include the cultural and spiritual values associated with water resources, especially to Indigenous communities, in consideration of this risk type. | Potential impacts to the community from BHP’s access to and use of water resources within the catchment include reduced water supply to communities, aesthetic impacts to recreational use for water or contamination of water sources, with potential reduction in availability for community water use. Ineffective catchment governance and regulation can make them more complex to manage. The potential impacts to the environment may include changes to natural groundwater levels, changes to stream flows, water quality issues in ground, surface or marine environments and reduced pressure in groundwater aquifers that in turn, may affect the biodiversity, habitats and species that rely on the water sources. Potential environmental impacts can contribute to adverse community impacts and affect the value of the water resource for future generations. Unsustainable use of the water resource may affect production and a lack of understanding of the water resource may impact the operated assets ability to assess the long-term water management limitations and opportunities. Impacts to the water resource may have longer-term financial implications and threaten our business model, including our ability to expand or develop new resources and inhibit the delivery of social value. The cumulative impacts resulting from multiple users of the water resource within a catchment may exacerbate the potential community, environmental and business impacts discussed above. |

We seek to manage potential impacts to the water resource, including the environmental, community and business impacts, through:

|

| Closure | Risk associated with water-related closure objectives and outcomes for assets that are closing or have closed, which may include water quality, water accumulation or flow issues within the BHP footprint and beyond. | Ineffectively managed water-related closure risks across the entire lifecycle of an asset may adversely affect the environment (for example, contaminants in surface and groundwater, changes to landforms), communities, public safety and our costs associated with managing water now and over the long term. | We seek to manage our potential water-related closure risk through closure planning and early and progressive closure management. Closure planning is an important control across BHP’s assets. Closure strategies should consider issues, such as pit void lake formations, acidic and metalliferous drainage, saline water accumulation, dewatering, extreme weather, water quality and potential impacts to both surface water and groundwater. For more information refer to the Closure webpage. For more information on the financial provisions relating to closure liabilities refer to the BHP Annual Report 2025, Operating and Financial Review 7 – How we manage risk. |

| Compliance | Risk associated with changes in the regulatory settings, including the nature and extent of regulation related to water allocation, permits, tariffs and reporting obligations. Our operated assets function in mature regulatory environments for water and regulation compliance requires constant vigilance. The regions where we operate have reasonably mature regulatory systems for water extraction, use and discharge, although their approach and requirements vary by operated asset and jurisdiction. Typically, we are granted a licence to extract a prescribed quantity of water for a defined period and to discharge water at certain quantity limits and quality standards. These limits and standards are determined by relevant local regulatory authorities. | Alleged or actual non-compliance could result in adverse impacts ranging from lower-order infringements through to financial penalties, enforcement orders or proceedings, social activism or increased cost to BHP. Environmental impacts may result in regulatory breaches or legal liability. | Compliance, monitoring and reporting requirements are usually defined through permits and licences. In addition to local regulation, we apply a range of internal standards. Refer to Governance and oversight on the Water webpage and the Nature and environmental performance webpage for a detailed overview of these. There are a few instances where water use and discharge may not be regulated via licences or permits. Our internal standards require that, in these instances, BHP follows relevant local guidance e.g. Australian and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council (ANZECC) Water Quality Guidelines. Application of these guidelines typically requires consideration of the water quality in receiving water bodies. Ongoing engagement with regulators helps us to understand their priorities, how regulatory requirements apply to our operated assets and at a catchment level address existing non-compliances regarding surface water and groundwater. |

| Dewatering | Risk associated with management of dewatering activities and surplus mine groundwater and surface water (such as levels, volumes and pressures). Many of BHP’s ore bodies are below the natural groundwater level and to access the ore we need to pump water to reduce the groundwater levels in order to access the ore bodies safely. Dewatering is an important activity that supports mine production, by enabling access to ore located below the water table or enabling access to ore by supporting pit stability. | Dewatering can potentially impact geotechnical stability and safety, water supply, excess water management, the environment, communities and production. |

We seek to manage the risks associated with dewatering through:

|

| Extreme weather | Risk associated with extreme weather can cause drought, snow or flood events and may arise from acute (event-driven, including increased severity of extreme weather events) or chronic (longer-term changes) to climate cycles. | Extreme weather events may contribute to adverse production, environmental, community and reputational impacts. For example, ineffective management during drought conditions may constrain production due to limitations on water availability. Ineffective management of excess water also has the potential to affect geotechnical stability and safety, prevent site access, cause injuries or fatalities or physical damage to infrastructure due to flooding and affect the environment, communities and production. Infrastructure damage may result in adverse impacts to communities where we operate where BHP supplies services such as power, drinking water or waste water treatment services directly to those communities. |

The protection of our workforce from the potential impacts of extreme weather forms part of the overall management of health and safety risks. We seek to manage potential impacts, including through:

|

| Marine | Risk associated with the alteration in marine water quality (sea or coastal areas), water or seabed levels or biophysical changes to marine environments. Marine ecosystems are susceptible to impacts resulting from changes to the physical (e.g. temperature and pH) and chemical (metal, hydrocarbon concentrations) parameters of the water body. This risk can arise from discharges from desalination facilities or from port facilities located in proximity to communities and/or key marine areas. | Due to regional differences in marine ecosystems and potential cumulative impacts, the type and extent of potential impacts to the marine environment for each of our operated assets may be different and could result in increased costs for mitigation, offsets or financial compensatory actions or obligations. Potential adverse impacts include water quality impacts due to loss of hydrocarbon or chemical containment. Impacts to water quality have the potential to affect both the environment and communities. Brine discharges at desalination facilities may result in the alteration of marine ecosystems. Loss of containment or other major incidents may affect BHP’s licence to operate and/or production. |

Controls for chemical containment include:

Mitigating controls include:

Controls for desalination and port facilities include:

To help avoid or minimise potential or actual adverse impacts associated with smaller discharges in marine environments, treatment, sediment, erosion, dust minimisation and other collection and/or treatment systems are utilised. |

| Tailings | Risk associated with the design, operation, maintenance, governance and reliability of tailings storage facilities. | Potential adverse impacts arising from the ineffective management of tailings storage facilities (TSFs) can range from seepage and interrupted production to catastrophic failure incidents with the potential for multiple injuries and fatalities, widespread environmental damage and extensive community disruption and potential damage to community infrastructure, businesses and livelihoods, with flow-on financial and reputational impacts. | In FY2019, we introduced mandatory minimum performance requirements for TSFs that govern how we manage TSF failure risks across BHP and outline applicable processes, including business planning, risk assessments and management of change. Our internal standards and guidance for TSFs have been updated to align with the Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management. For more information on tailings refer to our Tailings storage facilities webpage. |

| Water access, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and water-related human rights | Risk associated with providing access to safe and reliable drinking water (potable water) and appropriate sanitation and hygiene facilities, including availability of appropriate water infrastructure to supply WASH facilities. The remote nature of many of our operated assets means BHP can sometimes contribute to improved access to water and sanitation as we are often the sole supplier of water to our workforce for drinking and sanitation, and the manager of effluent. This role sometimes extends to neighbouring communities. | Ineffective WASH practices and infrastructure may result in the inability to provide the required quantity and quality of drinking water or sanitation. This may result in illness and potential fatalities, and could also disrupt our operated assets, impact communities and the environment, have adverse financial and reputational impacts and inhibit the delivery of our social value proposition. Our operated assets also have the potential to affect the cultural and spiritual values associated with water resources, including potential human rights breaches. | Understanding the baseline quality of the water we receive, the performance of our treatment plants and monitoring the water produced are our WASH priorities. Our Water Stewardship Position Statement commits us to uphold the basic human right to water access and sanitation within our operations and to contribute to realising this right within communities. We do this by seeking to ensure members of our workforce have access to clean drinking water, gender-appropriate sanitation facilities and hygiene at our workplaces and within our communities where we are the supplier of these services. We have global drinking water standards that our operated assets are required to meet. Other controls include appropriate infrastructure that is constructed, designed and operated to meet external water quality standards by suitably qualified persons and is regularly maintained, inspected, monitored, with exception reports and responses, emergency response and business continuity planning. Regular maintenance of water infrastructure, such as treatment plants, pipelines and tanks, is critical to ensure water is adequate for our operated assets, both in quantity and quality. Our processes for conducting community and human rights impact and opportunity assessments (CHRIOAs) and integration with our Risk Framework are a control applied in certain circumstances to assess direct impacts to the workforce and local communities, as well as potential impacts to other human rights, such as Indigenous, spiritual and cultural rights. |

| Water quality | Risk associated with changes in the chemical attribute of water, which may occur from runoff or seepage (including from exposed ground, pit slopes, waste rock), infiltration from water, tailings and process facilities, infrastructure, and increases in salinity due to long-term storage of water. | Changes to the quality of water that runs through or under an operated asset can affect the surrounding groundwater resources and streams. This can affect other water users and the environment. Changes in water quality can also constrain production or result in water accumulation over time (due to discharge restrictions), which makes management during extreme rainfall events more challenging. This risk can persist for years after mining activity has ceased. |

Management of water quality risks requires an understanding of what contributes to changes in water quality, how this may affect sensitive receptors within the environment and/or communities, and the appropriate management measures required. Controls include:

|

| Water security | Risk associated with current and future balance between water supply, including the capacity and reliability of water supply infrastructure, and demand for all relevant users and related to the ecosystem function. A continuous and sustainable water supply is critical to our operated assets, including provision of sufficient and well-maintained water infrastructure. | An inability to secure water access can constrain production and have regulatory, legal and financial implications. It may also adversely impact the environment or community, which was discussed as part of the Catchment risk area of this table. Insufficient or poorly maintained water infrastructure can result in the inability of water infrastructure to supply the required quantity or quality of water necessary for our operated assets. This can result in reduced production and other adverse impacts, including to the long-term viability of our operated assets. The level of risk is dependent on location and climate impact, water availability and supply. For example, availability has been a risk at New South Wales Energy Coal in the Hunter region of eastern Australia due to extended periods of below-average rainfall. |

An adequate understanding of technical aspects of the water resource, hydrological conditions and/or long-term changes in water availability and management is critical to ensure ongoing supply. In addition, understanding demand through water balances, predictive modelling and monitoring is central to effective water security. Many of the controls in place for the management of catchment risk are applied for management of water security risks. Refer to controls listed above for the Catchment risk area of this table. We seek to use lower-quality water where feasible and recover and recycle water to reduce withdrawal of new water from the environment. Water infrastructure needs to be:

Regular maintenance of water infrastructure, such as treatment plants, pipelines and tanks, is critical to ensure water is adequate for our operated assets, both in quantity and quality. |

Climate-related risks are discussed in many of the risk factors in the BHP Annual Report 2025, Operating and Financial Review 7 – How we manage risk. Indirect potential outcomes of these changes may include coastal erosion, storm tide inundation and production of toxic microorganisms and, over the longer term, reduced rainfall could create water security issues while increasing the need to manage excess water.

The effects of climate change could create or increase business risks (e.g. the risk of production loss due to increased flooding). Assessments of the potential impact of future climate change policy and regulatory, legal, technological, market and societal changes on water-related risks have a degree of uncertainty given the wide scope of influencing factors and the countries where we do business. Under our mandatory minimum performance requirements for risk management, material risks are required to be reviewed periodically to evaluate performance. These reviews are designed to ensure developments in climate change science and policy and other relevant regulatory, legal, technological, market and societal factors, including areas of uncertainty, are considered annually in our evaluation of operational water-related risks.

Our operated assets are required to apply BHP’s Risk Framework and our Climate Change Global Standard to identify, assess and manage physical climate-related risks, including options to build climate resilience into their activities. We are progressively undertaking studies to assess physical climate-related risk to inform potential adaptation responses. We also require investment and growth opportunities to undertake analysis of climate-related risks. For more information see the Climate change webpage.

Water-related risk in the value chain

Water-related risks can indirectly affect operations via our value chain, from supply to operated assets to customers. For example, floods in one part of the world may affect supplies of a critical input or item of equipment necessary to sustain our operated assets. Additionally, tightening regulation around water discharges in a particular country or region may constrain our customers’ manufacturing operations. This may have flow-on effects to our ability to sell certain commodities.

BHP has potential exposure to water-related risks across our value chain and climate change may increase our future exposure. Customers and suppliers may be exposed to areas of high to extremely high water stress. Many are also located in areas with a higher likelihood of flooding. We need to understand these factors and respond to the challenges, working with our customers and suppliers. We are working towards increasing our understanding of potential water risks and opportunities across our supply chain that we may be able to contribute to or influence reducing or enhancing respectively. One of the key changes in the updated Environment Global Standard, released in April 2024, included an increased focus on risk and impact management, extending requirements for identifying and assessing nature-related risks to include those within BHP’s supply chain. In FY2024, BHP commissioned work to improve our process for how we understand and manage nature-related risk in the value chain.

For more information on value chain initiatives refer to the Value chain webpage.

Non-operated assets

For information on BHP’s interests in companies and joint ventures that we do not operate refer to the non-operated joint ventures (NOJVs) information in the BHP Annual Report 2025.

Water stewardship is as vital for our NOJVs as it is for our operated assets.

We engage with our NOJVs to better understand their management of water-related risks.

We have worked with Antamina and its shareholders to secure Antamina’s commitment to align with ICMM Mining Principles.

For more information on tailings storage facilities refer to our Tailings storage facilities webpage.

For more information on the Samarco NOJV, refer to BHP Annual Report 2025, Operating and Financial Review –10 Samarco and our Samarco operations webpage.

BHP Annual Report 2025, Operating and Financial Review 7 – How we manage risk describes how we manage risk across BHP, including with respect to our interests in NOJVs.

Water management can create opportunities

BHP recognises our positive environmental performance (including water stewardship) contributes to social value and the resilience of nature.

Effective water-related risk management can contribute to long-term business, social and environmental benefits, such as:

- increased productivity

- improved community benefits and resilience

- improved water disclosure and governance

- becoming a partner-of-choice to governments and communities in new and existing jurisdictions

- access to resources by obtaining and retaining rights to operate and expand our current operated asset base

- reduced liabilities and long-term legacy issues

- increased long-term business resilience

For an example of an opportunity from effective risk management, refer to our Pilbara water scheme success case study which discusses how WAIO manages dewatering risks. Dewatering at WAIO produces more water than is required for mining activities.

BHP’s Water Stewardship Strategy seeks to leverage and develop technology solutions to prevent or significantly reduce adverse water-related impacts, increase water efficiency and deliver benefits beyond our operated assets.

We developed a roadmap of potential water technologies and are now trialling various water technologies. This roadmap identifies emerging and long-term challenges and strategic opportunities to resolve these through technology and innovation. The roadmap was developed by overlaying operated asset-level water-related risk with the water stewardship vision and objectives to leverage technology solutions that drive a step-change reduction in water-related risk and realise value creation opportunities. A Global Water Challenge was held in 2023, where technology providers submitted ideas for solutions to some of our challenges. For more information refer to our case study.