18 February 2020

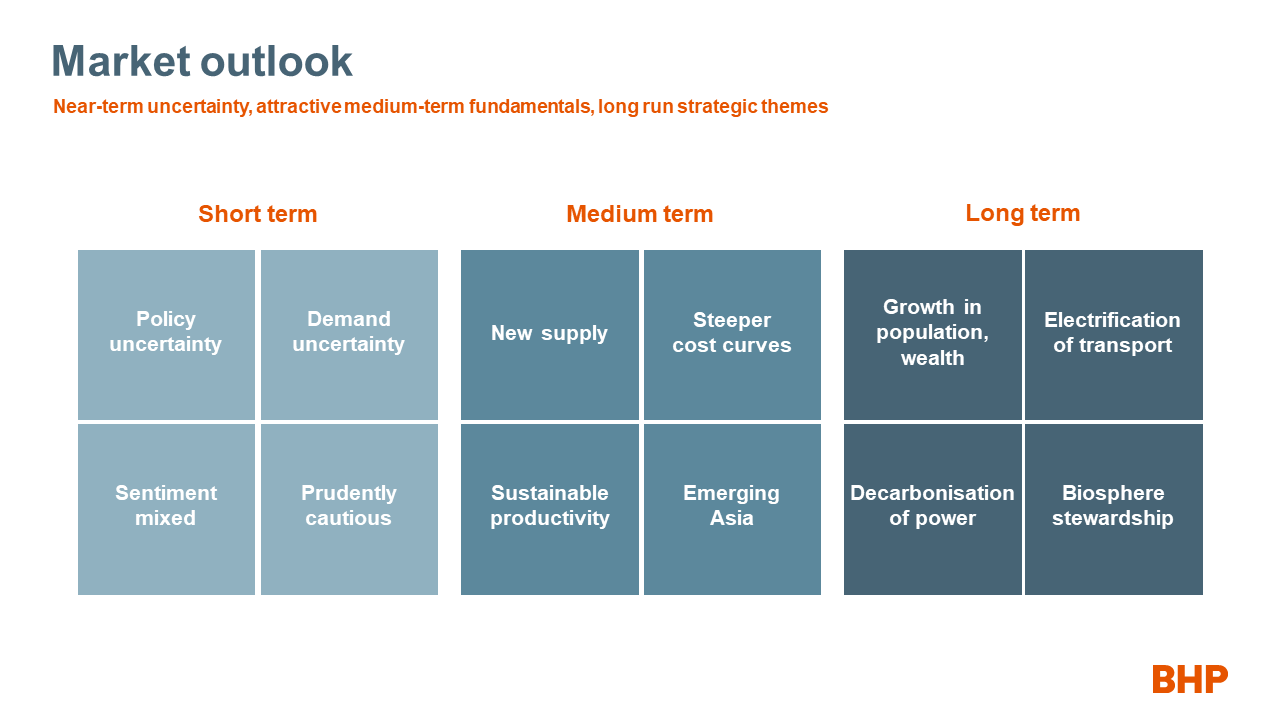

Six months ago, at the time of our full year results for the 2019 financial year, an air of prudent caution permeated commodity markets. On balance, events since that time have justified that caution.

The result has been a mixed price performance by our key commodities.1

Demand for oil, metallurgical coal and copper was weaker than expected in the 2019 calendar year, while demand for iron ore was higher than expectations. These outcomes reflected the impact of stunted growth in international trade, a recession in the global auto sector, a broad based slowdown in manufacturing in the developed world and a challenging year for non–China emerging markets, including India. The negative factors were partially balanced by robust growth in Chinese steel production and resilient growth in the United States for the majority of the calendar year.

For the 12 months ahead, we assess that directional risks to prices across our diversified portfolio are mixed, with the duration and intensity of the novel Coronavirus outbreak (hereafter Covid–19) a major source of uncertainty. This is arguably shrouding the impact of a patchy supply situation across many major commodity markets.

On balance, we expect to see lower iron ore prices on average in calendar year 2020 than in the year just concluded, with considerable two–way volatility in prospect. On the other hand, we expect conditions in metallurgical coal to improve somewhat versus those experienced in the second half of calendar 2019. Product differentials in both commodities are expected to remain favourable for higher quality producers, albeit narrower than the extremes of recent history, as steel industry profitability normalises.

Oil and copper prices are highly susceptible to swings in global policy and economic uncertainty. We consider the underlying commodity–specific fundamentals of both the oil and copper markets to be sound. We estimate that their forward looking short–term fair value ranges are similar to those we estimated both six and 12 months ago. Now that the US–China “Phase One” trade deal has been signed, a major drag on sentiment for much of calendar year 2019 has been neutralised. While this remains the case, we have no particular bias within those ranges.

The caveat is that while we hope that the Covid–19 outbreak is speedily contained within the March quarter, no one can be adamant about the precise timing. While the world is forced to live with this unknown, there is likely to be a sentiment discount in the prices of these commodities.

Looking beyond the immediate picture to the medium–term, we see the need for additional supply, both new and replacement, to be induced across most of the sectors in which we operate.

In many cases, this could lead to higher–cost supply entering the cost curve.

This projected steepening of cost curves can reasonably be expected to reward disciplined owner–operators with high quality assets.

On the demand side, we continue to see emerging Asia as an opportunity rich region. China, India, ASEAN and the global impact of China’s Belt and Road initiative are all expected to provide additional demand for our products.

As the true economic costs of trade protection are progressively recognised by global consumers, we anticipate a popular mandate for a more open international trading environment will eventually emerge.

Looking even further ahead, the basic elements of our positive long–term view remain in place.

Population growth and rising living standards are likely to drive demand for energy, metals, and fertilisers for decades to come.

New demand centres will emerge where the twin levers of industrialisation and urbanisation are still developing today. The electrification of transport and the decarbonisation of stationary power will progress. Comprehensive stewardship of the biosphere and ethical end–to–end supply chains will become even more important for earning and retaining community and investor trust.

The ability to both provide and demonstrate social value to our host communities and in our customer jurisdictions will be a core enabler of our strategy and a source of competitive advantage.

Against that backdrop, we are confident we have the right assets in the right commodities in the right jurisdictions, with attractive optionality, with demand diversified by end–use sector and geography, allied to the right social value proposition.

Even so, we remain alert to opportunities to expand our suite of options in attractive commodities that will perform well in the world we face today, and will remain resilient to, or prosper in, the uncertain world we will face tomorrow.

Table of contents

| World GDP > | China > |

| Major advanced > | India > |

| Steel > | Iron ore > |

| Met coal > | Copper > |

| Crude oil > | LNG > |

| Eastern Aust gas > | Aust power > |

| Energy coal > | Potash > |

| Nickel > | Freight > |

| Inflation > | EVs > |

The underwhelming performance of the global economy in calendar year 2019 stresses the point that while an increase in trade protection is not, on its own, a recessionary level shock for the global economy, it is an exceedingly unhelpful starting point for the pursuit of broad based growth across regions, expenditure drivers and industries.

Global economic growth

World economic growth was close to 3 per cent in real terms in calendar year 2019. That is down from an average of around 3¾ per cent in the prior two years. Each of the big four economies – the US, China, India, and Europe – recorded either flat or slower growth versus calendar year 2018. The US dollar has been relatively steady over the last twelve months. On a real, trade–weighted basis, it is around 1 per cent higher year–on–year (hereafter YoY).

Global trade growth has slowed from around 5½ per cent in calendar year 2017 to around 3¾ per cent in 2018 and, held back by policy headwinds, it is on track for a very disappointing outcome of around 1 per cent in calendar 2019.

The ratio of the growth in world trade to the growth in world GDP is an important indicator of the health of the global economic system at a point in time. Outside of recession years, the outcome for 2019 is the lowest in the four decades for which we have consistent data.

The underwhelming performance of the global economy in calendar year 2019 stresses the point that while an increase in trade protection is not, on its own, a recessionary level shock for the global economy, it is an exceedingly unhelpful starting point for the pursuit of broad based growth across regions, expenditure drivers and industries.

As a complementary observation, we strongly encourage policymakers to prioritise structural reforms at home as the surest route to sustainable productivity growth, and ultimately, prosperity.

These arguments highlight the importance of continued and vocal advocacy for free trade, open markets and high quality national and multilateral institutional design by corporations, governments and civil society.

Our base case is that world GDP growth will register around the mid–point of a 3 per cent to 3½ per cent range in calendar year 2020, roughly ¼ per cent higher than the projected outcome for 2019. The IMF and the OECD expect world growth of 3.3 per cent and 2.9 per cent in 2020 respectively.

Our view reflects the assumption that the Covid–19 outbreak is contained within the March quarter, some positive impact from the cessation in US–China trade hostilities, the support for growth coming from easier policy settings in the major economies, and some modest improvement in non–China emerging markets. The third and fourth arguments are linked. In particular, the change in the US monetary policy stance has brought some welcome relief to emerging markets, particularly for those with large hard currency external financing requirements and a reliance on portfolio inflows to service their deficits.

There is obviously clear downside risk to the outlook for China and its key trading partners if the Covid–19 outbreak is not contained within the time frame we have assumed in our base case.

Back to top ↑We support and stand with the Chinese people, especially our partners, customers, colleagues and vendors, and their families, at this difficult time.

China

China’s economic growth is expected to slow modestly in the coming years. We expect real GDP to register around 6 per cent in 2020 and between 5¾ per cent and 6 per cent in 2021. There are two key uncertainties. The first is the depth and duration of the economic impact of the Covid–19 outbreak. The second is the durability of the trade détente with the United States.

First of all, we support and stand with the Chinese people, especially our partners, customers, colleagues and vendors, and their families, at this difficult time.

The range of responses by the Chinese authorities to contain Covid–19, in tandem with the understandably risk–averse response of the population, will undoubtedly cause a sharp decline in economic activity in the March quarter. However, if the psychological and logistical impacts can be effectively contained within that window, construction and manufacturing activity (i.e. our steel and copper end–use sectors) should recover briskly to higher than normal run–rates in the June quarter. We expect that would redistribute demand within the year, but not change the annual outcome materially. Alternatively, if the impact of Covid–19 lingers, and construction and manufacturing have not been able to return to regular operation in April, then we expect to revise our annual forecast lower. This would then flow directly through to lower commodity demand and price expectations.

We estimate that almost 90 per cent of Chinese steel production is located in provinces with announced restart dates before the end of February 2020. The proportion is closer to 80 per cent weighting the provinces for infrastructure investment; closer to the mid-80 per cent range for floor space under construction and auto production; and above 90 per cent for exports and copper semi production.

Weighted by steel production, 58 per cent of provinces had already restarted as of February 10.

On the second key uncertainty, the Phase One trade deal with the United States neutralises the major headwind that was constraining the Chinese economy in calendar year 2019. Our forecasts in the mini–era of trade tensions have always been built on a two–step approach: we first estimate the likely impact of US trade protection on China’s export sector and we then deduce the appropriately calibrated countervailing domestic policy response to that shock.

We gauge that the monetary and fiscal policy settings that were put in place over the course of calendar 2019 were calibrated for an extended period of difficulty for the export sector. So were the truce to hold, that may provide some upside for calendar 2020 growth. Countering that, while it is comforting that tensions are not escalating, thus containing the sentiment impact of the tariffs, the tariffs themselves have not been completely reset to pre–dispute levels. So much of the direct negative impact that these imposts have on the Chinese and US economies will persist.

There is also the possibility that bilateral trade relations enter a new period of deterioration, should there be disagreements over the enforcement of Phase One, or should negotiations on Phase Two turn acrimonious. Our low case assumptions for Chinese GDP growth would then come into play. A low case built around trade war re–escalation allied to a contained viral outbreak would be in the region of 5¾ per cent. A low case built around trade war re–escalation plus lingering fears of Covid–19 constraining confidence, would push GDP growth down to around 5½ per cent.

Turning back to the performance of our key end–use sectors in calendar 2019, housing has been moderately firmer than expected, autos were considerably weaker, and machinery eventually met expectations of a trade war induced decline after a surprisingly strong start to the calendar year. Investment in transport infrastructure was slower to respond to policy support than in past fiscal easing cycles. Investment in the power grid and non–power utilities (e.g. waste treatment, water conservation) undershot our expectations. Consumer durables had a relatively good year.

In calendar year 2020, the growth of housing starts is expected to decelerate, but the long awaited rebound in housing completions seems to have finally arrived. Housing sales, which do not directly create commodity demand but have a leading relationship with building activity, are expected to plunge in the near term as Chinese buyers avoid high human contact activities such as off–the–plan property releases. Transport infrastructure and investment in non–power utilities are both expected to be strong, backed by policy tailwinds. However, an increasingly disciplined approach to capital allocation may constrain total spending on the power grid to a level similar to, or below, last year’s underwhelming figure. Auto production is expected to improve modestly from last year’s misfortune, although it could potentially lag other sectors somewhat given the importance of Hubei province to the aggregate supply.2 Machinery is expected to be soft, continuing the trend of the second half of calendar 2019. Consumer durables demand is expected to grow, but at a slower pace than last year.

We anticipate that national level housing policies and rhetoric will remain directed towards limiting speculation, building rental markets and fine–tuning the shantytown redevelopment programme. On the latter point, we note that the shantytown plan for calendar 2019 was significantly reduced from the prior year, which created a significant headwind for the volume of sales.

Over the longer term, our view remains that China’s economic growth rate should moderate as the working age population falls and the capital stock matures. China’s broad production structure is expected to continue to rebalance from industry to services and expenditure drivers are likely to shift from investment and exports towards consumption.

Nevertheless, China is expected to remain the largest incremental contributor to global industrial value–added and fixed investment activity through the 2020s even as its growth rates mature.

Within industry, we expect a concerted move up the manufacturing value–chain; and a concerted move outwards, with an emphasis on South–South cooperation along the Belt–and–Road corridors. More broadly, we anticipate environmental concerns will become an even more important consideration in future policy design than they are today.

Major advanced economies

After a very strong performance in 2018, when growth nearly reached 3 per cent, the US economy decelerated to around 2¼ per cent in calendar year 2019. The manufacturing sector was a major factor in the slowdown, particularly in the second half of the year. We expect overall growth will slow modestly again to around 2 per cent in calendar year 2020, which is of course an election year.

Long–term nominal bond yields in the US remain historically low at the time of writing. At times in the past twelve months the Treasury yield curve has been inverted. That partly reflects the growing unease among market participants about how much longer the current expansion can last. At eleven years, it is already four years longer than the historical average.

The US Federal Reserve lowered interest rates on three occasions in calendar 2019. This prudent course was adopted against a backdrop of trade policy uncertainty, jumpy financial markets, fading fiscal stimulus and rising corporate indebtedness. Furthermore, general inflation is moderate and some cyclical sectors and financial indicators are showing signs of fatigue. Those factors are offset by the reality of near full employment.

We note that the true costs of protectionism, particularly diminished consumer purchasing power, are only just beginning to be felt by US households and businesses. Weakening domestic consumption, (as purchasing power declines), and declining international competitiveness of US firms, (as input costs rise and the intensity of competition in the domestic market declines), are the inevitable medium–term outcome of such a turn inwards. Further, it is very unlikely that the current policy mix in the US will lower the nation’s trade deficit, which seems to be a core, if misplaced, objective of the current administration.

The US’ [non–oil] deficit is essentially a joint function of its low relative national savings rate and the US dollar’s role as the world’s principal vehicle currency.3 A return to the strategy of managed trade4, which is a key feature of the Phase One deal with China, and was also a lever used to address the rising competitive threat from Japan dating back half a century, is unlikely to be a durable success.

In Europe and Developed Asia, manufacturing conditions were weak. A material slowdown in the bellwether auto sector has been a headwind for both economies. In Developed Asia specifically, the slowdown in the global electronics sector also played a part in limiting growth, especially in the first half of calendar 2019. In Europe specifically, rising political and policy uncertainty, at both a national and regional level, have hurt business confidence.

For both regions, where the limits of monetary policy effectiveness may have been reached and public sector finances are stretched, we gauge that any upside to growth in the medium–term will have to come from external demand sources.

Shorter term, the possibility of the US instituting global auto tariffs would clearly be a damaging development for both Europe and Developed Asia. More positively, the electronics sector has shown clear signs of bottoming out, and autos are expected to show some improvement in calendar 2020, should trade policy or disrupted parts supply from China, which is an important hub in global auto supply chains, not intercede.

Back to top ↑

India

India’s economy stuttered in calendar 2019. The consensus view (which we shared) that the economy would bounce after Modi’s re–election has been confounded by domestic policy missteps and the impact of a poor global backdrop for emerging markets in need of foreign financing. Private sector confidence has suffered, credit is not flowing smoothly and GDP growth has fallen –2 per cent below trend. Civil unrest over a controversial citizenship bill has compounded the economic woes. The economy is probably bottoming out at the time of writing, with external headwinds fading somewhat, but it will almost certainly fall short of its typical rate of growth in calendar 2020.

Returning India to a healthy medium–term growth trajectory around 7 per cent will require a reduction in policy uncertainty, an increase in social stability, a greater focus on unlocking the country’s rich human potential and gaining and retaining international competitiveness. The moderately stimulatory Union Budget for the coming Indian fiscal year is hopefully a sign of renewed efforts in this regard.

Economic reform signposts were positive, in general, over the first term of the Modi government, underscoring the nation’s long run potential. We note in particular: its increased attractiveness for foreign direct investment over the last half decade; the introduction of a nationwide goods and services tax; a cut in the corporate income tax rate towards regional norms; an improved institutional setting for infrastructure planning and project execution; large scale efforts to bring rural residents into the formal identity and banking structure; and determined efforts to address non–performing loans in the banking system, particularly in the strategically important steel and power industries; and the move to issue sovereign debt abroad for the first time.

Important signposts on India’s expanding resource and energy footprint include: its new status as the world’s #2 crude steel producer; the fact it is jockeying with China for the status of our major customer for metallurgical coal; its position as the #2 incremental contributor to global oil demand growth; its rise up the LNG import ladder; its firm position as a top five potash importer; its increasing relevance as a consumer of copper; and according to the IEA, in a year in which global energy investment was flat, it led all major regions with 6 per cent YoY growth in calendar 2018.

In calendar year 2019, we were surprised by the overall strength of end–use demand for steel in China and by the elevated production run rates that have served this demand.

Steel and pig iron

Global crude steel production grew around 3½ per cent in calendar year 2019. Production became extremely unbalanced from a geographic perspective over the course of year, with China expanding by around 8¼ per cent and the rest of the world contracting by around –1½ per cent. Pig iron output growth did not keep pace with total steel production. A key contributing factor in the relatively slower growth of pig iron was a reshuffling of the global steel cost curve due to divergent price trends for iron ore, ferrous scrap and Chinese domestic versus seaborne coking coal.

In calendar year 2019, we were surprised by the overall strength of end–use demand in China and by the elevated production run rates that have served this demand. Real estate, which accounts for roughly two–fifths of steel demand, was firmer than expected led by high single digit growth in housing starts. Infrastructure accounts for a further 15 per cent of demand. The elements of this broad category that are most important for steel were solid but in no way spectacular. Parts of the manufacturing segment of end–use (cumulatively around 45 per cent of demand) were weak – for example passenger cars and machine tools. Others were firm – for example excavators, ships, trucks and agricultural machinery.

The balance of these trends led to another robust year for Chinese production growth, with the annual figure as reported by worldsteel rising to just shy of the one billion tonne mark at 996 Mt. The 2½ per cent growth we project for calendar year 2020 will see reported production move comfortably above that “mystical” nine zero level.5 We expect to revise down our China growth estimate for calendar 2020 if the Covid–19 outbreak prevents downstream activities from returning to normal by the end of the March quarter.

The lift in the profitability of Chinese steel mills since the inception of Supply Side Reform has allowed for a promising trend of improvement in sector–wide balance sheets over the last three years. Three–fifths of the targeted reduction in the liability–to–asset ratio (the full target being –10 percentage points from 70 per cent to 60 per cent) has been achieved to date. So while there is clearly much more to do on this front, and the pace of sector deleveraging slowed in calendar 2019 (as a result of merger activity, a revival of investment under the capacity swap scheme, and lower profitability than in the prior two years), the direction of travel has been heartening for both the financial sustainability of the steel industry and systemic financial system risk.

We estimate that 80 per cent is China’s long run equilibrium crude steel capacity utilisation rate, consistent with the stated objectives of China’s steel industry Five Year Plan (2016–2020). That compares to slightly less than 70 per cent at the cycle trough and upwards of 85 per cent at the height of policy induced disruptions. We note, however, that in the short term, industry participants are becoming increasingly wary of the impact of net new effective supply being brought online under the auspices of the capacity swap scheme. Chinese policy makers also seem to be giving this issue increased attention. We estimate that if all of the projects currently underway or planned under this scheme were to come online, the equilibrium utilisation rate would be very difficult to achieve without a demand scenario close to our high case.

More broadly, we firmly believe that, by mid–century, China will almost double its accumulated stock of steel in use, which is currently 7 tonnes per capita, on its way to an urbanisation rate of around 80 per cent6 and living standards around two–thirds of those in the United States. China’s current stock is well below the current US level of around 12 tonnes per capita. Germany, South Korea and Japan, which all share important points of commonality with China in terms of development strategy, economic geography and demography, have even higher stocks than the US.

We estimate that this stock will create a flow of potential end–of–life scrap sufficient to enable a doubling of China’s current scrap–to–steel ratio of around 22 per cent by mid–century.

The exact path to this end–state is uncertain. Among the range of possibilities we consider, our base case is that Chinese steel production has entered a plateau phase, with the literal peak to occur no later than the middle of this decade. Our low case7 for China, which underpins our global view on steel–making raw materials, assumes that the peak year is contemporaneous. The industry is then assumed to immediately embark upon a multi–decadal decline phase in the annual output of both steel and pig iron, highlighted by an even more aggressive long–run scrap–to–steel ratio increase than the doubling outlined above. Ex–China, in the low case, we discount India’s long–run capacity additions plans by 40 per cent.

The recovery in rest of the world output seen across calendar year 2017 and 2018 reversed abruptly in calendar year 2019. That outcome was the result of broad based weakness across almost all of the major regions. The Middle East and ASEAN, which are medium sized regional markets, were the exceptions to the rule.

India’s crude steel output increased by just 1.8 per cent in calendar year 2019, to 111 Mt, while pig iron output edged up around 2 per cent YoY. End–use demand was significantly below trend in the year, which will be remembered mostly for extremely heavy destocking. India’s output narrowly passed Japan’s a year ago, making India the second largest steel producer globally, a position we expect it to retain. In 2030, we estimate that the Indian low case for crude steel production will be almost double the Japanese high case for the same.

Steel production elsewhere in Asia in the 2019 calendar year has been mixed: weak in the North and firmer in the Southeast. Japanese output contracted by –4.8 per cent YoY (to 99Mt), while South Korean production was down –1.4 per cent YoY (to 71 Mtpa). Operational issues have been prominent in North Asia, alongside pronounced weakness in flat products due to weak global auto sales. Southeast Asia increased steadily, led by Vietnam and Indonesia amid a rapid build–up of blast furnace capacity in the region.

Europe has seen a dramatic slowdown (–5.6 per cent YoY), with some mills curtailing production due to unfavourable demand conditions, and in some instances, higher carbon levies. The production of each of the three largest national producers, Germany (–6.5 per cent), Italy (–5.2 per cent) and Turkey (–9.6 per cent) declined heavily over the year. The latter two examples reflect general recessionary conditions, while Germany has endured a recession in its outwardly focused auto industry. End–use trends across the region have been mixed, with flat products in considerable cyclical difficulty but long products still enjoying some downstream demand from construction. In Germany specifically, where the dwelling stock has not kept pace with rising underlying demand, an extended period of rising building activity could be in prospect over the medium term.

Steel production growth in North America dipped –0.8 per cent YoY in the calendar year 2019 with a 120 Mtpa run–rate (despite the US producing 88Mt, +1.5 per cent). However, US growth seems destined to slow in the 2020 calendar year, as demand has moderated, the monthly pace has been negative YoY for some months, and the sharp decline in US HRC prices from their tariff–induced peak is not encouraging a lift in utilisation. The price decline has unwound most of the differential to European and Chinese benchmarks that emerged in early 2018 when the US administration first flagged their intention to introduce steel import tariffs. Production in South America also declined by –8.4 per cent YoY in calendar year 2019.

The CIS (Commonwealth of Independent States), which has been a laggard region through most of the upswing, retained that status, with another small annual decline recorded.

Back to top ↑There will be three major forces sponsoring iron ore price volatility in the coming year. The first is the uncertainty created by the impact of the Covid–19 outbreak. The second is higher than normal intra–year demand volatility. The third is seaborne supply uncertainty.

Iron ore

Iron ore prices (62 per cent, CFR) ranged between $78/dmt and $126/dmt over the first half of the financial year, averaging around $95/dmt. The uneven nature of the recovery in Brazilian exports, and a patchy production period for the other seaborne majors (in aggregate) have kept the supply fundamentals tight against a backdrop of firmer than expected end–use demand in China and loose enforcement of winter cuts. Seaborne lump premia were firm in the same time period, trading in the range of $0.10–0.44/dmtu and averaging $0.21/dmtu in the half.

Chinese port stocks touched a multi–year low point of 114Mt at the height of the disruption, before gradually building back up to 127Mt at the end of calendar year 2019. That is substantially lower than the closing position of 142Mt in calendar year 2018.

There will be three major forces sponsoring iron ore price volatility in the coming year. The first is the uncertainty created by the impact of the Covid–19 outbreak. The second is higher than normal intra–year demand volatility. The third is seaborne supply uncertainty.

As outlined in the steel section, if Covid–19 is effectively and demonstrably contained within the March quarter, we expect that an accelerated run–rate in the construction and manufacturing sectors for the remainder of the year can make up for the loss of activity seen at the outset of the year. If the outbreak is not contained within that time frame, or it re–emerges after a period of apparent containment, then that would be damaging for both real activity and market sentiment. The second point regarding intra–year demand volatility is also Covid–19 related. The sprint required to meet the annual plans of public and private entities in China in nine months rather than twelve (to stylise) will amplify the normal seasonal swings in steel end–use, potentially creating a shift from “famine” to “feast” for the iron ore market.

The observation that seaborne supply conditions for this calendar year and next are highly uncertain, both in aggregate and in terms of quality profile, is self–evident. While we do not think that the current constraints on Brazilian exports are informative for long run equilibrium pricing, we reiterate that the normalisation process could be a multi–year event. The inevitable ups and downs of the path back to a stable and predictable Brazilian export performance can be reasonably expected to generate volatility in pricing. While much less significant for the global trade than the Brazilian question, India’s iron ore mining license auctions, which cover around one–third of the country’s total production, also have the potential to be disruptive if they are not concluded in a timely fashion.

We estimate that price sensitive seaborne supply increased by around 32 Mt (62 per cent equivalent basis) in calendar 2019. That is a rational response to the transitory nature of current conditions. Chinese domestic iron ore concentrate production has also increased modestly, as expected. Annual domestic production in 2019 was 212 Mt (also 62 per cent equivalent), +15 Mt YoY. Accounting for the lift in output on a cyclical trough to peak basis, we estimate that domestic supply has increased by +31 Mt.8 Going forward, we expect that, in addition to structural market based drivers, safety and environmental inspections are likely to have a material influence on the average level and seasonal volatility of Chinese domestic iron ore production.

Our coastal blast furnace customers in China experienced reduced margins in calendar 2019 relative to those they enjoyed in 2017 and for much of 2018. High seaborne iron ore prices, lower scrap prices and a wide gap between premium domestic coking coals and the seaborne equivalent have reduced the competitive advantage these customers normally enjoy relative to inland blast furnaces with captive iron ore and scrap–based EAFs. At the height of this unusual constellation of events, when the 62 per cent index was trading above $120/t and steel margins fell to single digits, there was a major incentive to increase commercial blending arbitrage on the coast. Logically, this led to a reduction in realised spreads both above and below the 62 per cent index. More recently, as iron ore prices receded below $100/t, and margins improved, spreads have moved out again (i.e. more favourable for higher grades, less favourable for lower grades).

In the medium to long–term, the on–going Supply Side Reform, the expected migration of steel capacity to the coastal regions, the inexorable trend towards larger furnaces and more stringent environmental policies – Chinese controls being now, holistically, the most demanding in the world – are all expected to underpin the demand for high quality seaborne iron ore fines and direct charge materials such as lump. The South Flank project, which was approved in June 2018 and was 58 per cent complete at the time of writing, will raise the quality of our overall portfolio, in addition to increasing the share of lump product in our total output.

We remain of the opinion that around two–thirds of the movement in product quality differentials since the introduction of Supply Side Reform will be durable. The recent narrowing of differentials is an anticipated development on the path to this gravity point.

We continue to contend that the long run price will likely be set by a higher–cost, lower value–in–use asset in either Australia or Brazil.

Our low case for the iron ore price is predicated on a contemporaneous peak in Chinese pig iron production; a heavy discount to India’s long–run steel capacity addition plans; the return of a low–margin environment for Chinese steel mills, with an adverse impact on quality differentials; and transformational productivity gains for all of the major seaborne producers.

Back to top ↑The sharp decline in metallurgical coal prices was principally the result of broad based demand weakness in all major consumption regions but China, consistent with the unbalanced geographic profile of pig iron production that emerged over the course of the year.

Metallurgical coal

Metallurgical coal prices10 have ranged from a low of $132/t FOB Australia on the PLV index to a high of around $193/t over the first six months of the financial year. MV64 has ranged from $117/t to around $175/t; PCI has ranged from $86/t to $122/t; and SSCC has ranged from $74/t to $93/t. Three–fifths of our tonnes reference the PLV index, approximately.

For the half year overall, the PLV index averaged $151/t, down by –26 per cent compared to the previous half. The differential between the PLV and MV64 indexes has averaged 11.4 per cent in the calendar year to date, down –2.2 percentage points from the previous half.

The sharp decline in metallurgical coal prices was principally the result of broad based demand weakness in all major consumption regions but China, consistent with the unbalanced geographic profile of pig iron production that emerged over the course of the year. Uncertainty regarding China’s approach to the volume of coal imports, both in aggregate and on a port–by–port basis, was an additional headwind for the physical trade at times during the year.

Outside of what eventually turned out to be a strong performance by Chinese imports, the second half of the 2019 calendar year presented a bleak picture of demand. Indian pig iron production edged up around 2 per cent YoY in calendar 2019, with a high level of finished steel inventories, and weaker end–use demand as the economy stuttered, constraining blast furnace utilisation rates. An extremely tepid return to the seaborne trade post the [extended] monsoon was a major disappointment for a coking coal market that was already under pressure. Longer term, we anticipate India and Southeast Asia will be the main sources of incremental growth in seaborne demand for metallurgical coal.

Industry wide shipments to North Asia and Europe were both weak. In Europe, where pig iron production has declined by around –4 per cent YoY, conditions were particularly difficult.

On the supply side, the return of mines from extended maintenance, improved coal throughput and lower vessel queues at the major Queensland ports allowed exports to rise modestly over the course of calendar year 2019. Canadian exports also increased somewhat, as did landborne exports from Mongolia. Russian seaborne exports of weaker coking coals and PCI lifted markedly.

The exceptions to the general trend of higher seaborne supply were the United States and Mozambique. US exports, which are the traditional source of swing supply in the metallurgical coal trade, predictably swung out as PLV prices dipped into the $130/t to $150/t FOB range.

Domestic Chinese hard coking coal supply was largely unchanged from the previous year, while supply in the premium low–sulphur bracket declined against a background of safety and environmental pressures. With pig iron production growing strongly, China’s call on imports logically increased, notwithstanding the regulatory ambition to maintain a relatively flat level of total coal inflows versus the prior calendar year. Total imports of coking coal were up by 18 per cent YoY year–to–date to 80Mt annualised as of November. Shipments from Australia to China were up 9.2 per cent YoY to around 42 Mt annualised.

We estimate that since the start of the Supply–side reform, Chinese capacity for hard coking coal production has declined by around –14 per cent, while total coking coal capacity is down by around –9 per cent. That gap reflects capacity growth at the lower end of the quality spectrum in calendar 2019. Production has fallen by less than capacity. The gap between capacity and production cuts reflects higher utilisation of more efficient, modern mines. The space for this development was created by the closure of less efficient, less safe and less environmentally conscious operations, with water stewardship now a major regulatory theme.

The continued policy focus on environmental considerations should increase the competitiveness of high quality Australian coals into coastal China, at the margin. Uncertainties in this regard are the future level of Mongolian exports (mainly mid volatile, low sulphur) and US–China trade relations (US met coal imports were on China’s retaliatory tariff list, but they are now an item that could contribute to the aspirational “energy purchase plan”). Further, while there also remains potential for intra–year import curbs during lower demand periods, our view is that in the future, as in the past, these curbs will tend mostly to affect energy coal and lower grades of met coal with higher sulphur content, and/or cargoes destined for lower tier ports. The vast majority of premium met coal cargoes are destined for tier one ports. Strained geopolitical relationships beyond the US–China trade issue are a further source of uncertainty.

We maintain our constructive medium–term outlook for metallurgical coal prices, especially in the PLV bracket. The Supply Side Reform and heightened environmental, safety and water controls in China, and depleting premium–quality supply in traditional export basins, are all constructive for the market. In the medium–term, enhanced value–in–use realisation for low volatile matter, low impurity, high “coke strength after reaction” products and Chinese supply–side discipline are both expected to pertain. So while prices will always fluctuate widely within and across years based on both cyclical and idiosyncratic influences, (as they have done in recent history), it seems reasonable to suggest that met coal prices can sustain above long run marginal cost, if given an average pig iron demand backdrop to work with, for some time to come.

Similar to our view on iron ore, our technical and market research, and customer liaison, indicate that the premia presently being attracted by high quality coking coals are predominantly a structural, rather than cyclical phenomenon, although there is certainly a transitory component to them that will fade with time.

In coming years, most committed and prospective new supply is expected to be in the mid quality bracket. And while there is a developed and growing market for mid quality coking coal in, for instance, India and Southeast Asia, the relative supply equation underscores that a durable scarcity premium for true PLV coals is a reasonable starting point for considering medium terms trends in the industry.

Our low case for the PLV coking coal price is predicated on a contemporaneous peak in Chinese pig iron production; a heavy discount to India’s long–run steel capacity addition plans; the return of a low–margin environment for Chinese steel mills, with an adverse impact on quality differentials; a return to excess capacity and lax environmental controls in Chinese coal mining; and sizeable productivity gains for all of the major seaborne producers.

Back to top ↑Grade decline, resource depletion, increased input costs, water constraints and a scarcity of high–quality future development opportunities are likely to result in the higher prices needed to attract sufficient investment to balance the copper market.

Copper

Copper prices ranged from $5537/t to $6211/t ($2.51/lb to $2.82/lb) over the first half of the 2020 financial year, averaging $5841/t ($2.65/lb).11 The price range and the average were around –5 per cent lower than in the prior half. Price trends have been heavily influenced by the whip–sawing of expectations with respect to the US–China trade confrontation. The sentiment impact from Covid–19 has weighed heavily on prices in the early part of calendar 2020.

In the absence of Covid–19, we assess that the forward looking fundamentals for copper would support an approximate trading range of $6000/t to $6500/t, based on an average rate of disruption to primary supply (i.e. an outcome closer to the historical 5 per cent loss, higher than the last two years). As matters stand, a return to that fundamental range is expected to require demonstrable containment of Covid–19.

In contrast to steel, Chinese end–use demand for copper was weaker than expected in calendar year 2019. Dwelling completions12 declined for much of the period, the auto sector has remained weak, electronics have been mixed (weak early in the calendar year and then gaining momentum late) while investment in the power grid fell behind budget early in the year and never came close to catching up.13 Partially offsetting those disappointments, machinery was more resilient than expected early in the calendar year (ahead of a second half decline that we did anticipate) and household appliances have been solid. The net result is that demand grew by less than 1 per cent in calendar 2019. For calendar 2020, our Chinese refined copper forecast of around 1½ per cent comes with the same caveat as steel and steel–making raw materials regarding Covid–19: if end–use activity has not returned to normal in April, we expect to revise our forecasts downwards.

By end use sector, our baseline outlook for calendar year 2020 comprises a positive view on housing completions, which are set for healthy growth after a multi–year downtrend. Electronics are expected to continue on an improving trend, while autos will stage a modest recovery. Investment in power infrastructure, though, is expected to be flat or lower in calendar 2020, with central efforts to instil capital discipline in grid expenditure expected to limit the scale and number of new projects approved.14 Consumer durables are expected to slow, with demand for air conditioners due for a pause after a frenetic increase over the last few years.

Demand from the rest of the world also disappointed in calendar year 2019. Within that overall judgement the United States was the most resilient performer among the major regions. Private housing starts have rebounded from around 1.2 million annualised at the time of our full–year 2019 financial results to a 13 year high of more than 1.6 million in December 2019. Private housing completions were tracking at a solid 1.277 million in the same month. On the other hand, forward looking indicators of business investment, such as new capital goods orders, have been pointing towards weaker outcomes. Manufacturing was softer in the second half of the calendar year than the first, with official industrial production and private sector purchasing manager indexes both describing a mild contraction in activity. Also, the inventory–to–sales ratio of manufacturers rose steadily over the last 12 months. The fact that this mixed catalogue of trends counts as outperformance tells you what you need to know about manufacturing in Developed Asia and Europe over this period.

On the global scale, upstream electronics demand growth was weak for much of the year, but it is on an improving trend as calendar 2020 opens. Global semiconductor sales bottomed in August of 2019 at –15.9 per cent YoY. The rate of contraction has since eased to –5.5% YoY. Auto sales are on track for a second year of decline at the global level in the 2019 calendar year. The weakness in autos and electronics has exerted a considerable drag on demand from developed Asia and Europe.

Turning to supply, the primary supply disruption rate for the full 2019 calendar year is expected to be between 4½ per cent and 5 per cent. The spot estimate from Wood Mackenzie for the year–to–date ahead of December quarter reporting is 4.4 per cent. Within that figure, concentrate producers are tracking at 3.3 per cent while SxEW15 operations have recorded a striking 9.2 per cent outcome. Those estimates compare to around 3½ per cent in calendar 2018. From a copper price perspective, the increased quantum of supply disruptions year–over–year has been a partial offset to the weaker than expected demand environment described above.

Treatment and refining charges (TCRCs) for copper concentrates have experienced a steady march lower (i.e. terms more favourable to the producer) in the second half of the calendar year, partly reflecting the introduction of new smelting capacity in China and partly due to a shortage of high quality, low impurity material. The FastMarkets TC index has ranged between a high of $56.7/dmt and a low of $49.2/dmt, averaging around $52/dmt.16 That compares to the 2019 benchmark settlement (in which we do not participate) of $62/dmt.17 Shanghai Grade A cathode premia were volatile, but they increased on average in the second half of the calendar year 2019.

Taking the longer historical view, a marked five year downward trend in TCRCs can be observed. We interpret this as a fundamental signal that the balance of demand for high quality concentrates, vis–à–vis their reliable and consistent supply, has been on a structurally tightening path. Supporting that observation, the steady downward trend in TCRCs has emerged at a time when the base price of copper has seen considerable two–way volatility, but without a clear directional trend for much of the period. As we move closer to the point where the copper market in aggregate moves into structural deficit (see below), it is possible that TCRCs could be lower, on average, in the coming five years than in the five years just gone.

A more transparent and liquid indexation model would assist the industry to appropriately value the wide variety of higher and lower impurity products that comprise the aggregate supply of copper concentrates.

Developments in China will continue to be vital for the copper market. Major themes include the evolution of the regulatory environment for scrap imports; the scale of investments in domestic and regional scrap processing capability; lifecycles of copper intensive capital stock; technical standards for aluminium usage in power cables; substitution trends in renewables power equipment; and the evolution of policies towards the production and uptake of electric vehicles.

Looking at the first of these questions in more detail, China’s curbs on low grade scrap imports, which have now extended to a more controlled inflow of higher grade scrap, should be positive for primary demand, for a time. But beyond an inevitable adjustment phase, we do not believe this development is likely to sustainably alter longer run market balances, the incentive to invest in scrap processing capacity globally, or mine inducement dynamics. It could, however, have an impact on the incentive for local firms to invest in scrap collection and processing capacity at home. As time goes on, we expect that customs priority will be given to even cleaner scrap, with copper–contained now possibly converging on an average of above 90 per cent, even more stringent than our prior view of 85 to 90 per cent.

Turning to the outlook for the aggregate refined copper balance, demand and supply (primary plus secondary) are expected to advance roughly in parallel for the next couple of years. Solid demand growth is expected to be matched with a combination of committed green and brownfield supply (including our Spence Growth Option, which is expected to be completed in the first half of financial year 2021) as well as rising scrap availability. Beyond that near–term window, depending upon exact project timing and year–to–year demand swings, the expected arrival of a cluster of new supply from Peru, Chile, central Africa and Mongolia in the calendar 2022 to 2024 period could temporarily tilt the market into modest surplus in one or more of those years.

Subject to the above caveats on precise timing, a structural deficit is expected to open in the mid–2020s, at which point we see some sustained upside for prices. Grade decline, resource depletion, increased input costs, water constraints and a scarcity of high–quality future development opportunities are likely to result in the higher prices needed to attract sufficient investment to balance the market.

It is these parameters that are critical for assessing where the marginal tonne of primary copper will come from in the long run and what it will cost. We estimate that grade decline could remove –2 Mt per annum of mine supply by 2030, with resource depletion potentially removing an additional –1½ and –2¼ Mt per annum by this date, depending upon the specifics of the case under consideration.

Our view is that the price setting marginal tonne a decade hence will come from either a lower grade brownfield expansion in a lower risk jurisdiction, or a higher grade greenfield in a higher risk jurisdiction. Neither source of metal is likely to come cheaply.

Our low case for the copper price is predicated on stern competition for primary supply from scrap; on–going aluminium substitution in China; low case macro assumptions that constrain traditional end–use demand; low case EV penetration [below the vast majority of published mid–cases]; 60kgs of copper intensity per EV [–20kgs from the mid]; and low case macro cost inputs [for example USD/CLP close to 700].

Back to top ↑

In the long-term, we continue to see compelling market fundamentals, underpinned by rising transport and industrial demand in the developing world in addition to a steepening cost curve underpinned by natural field decline.

Crude oil

Crude oil prices (Brent) ranged from a low of around $57/bbl to a high of around $70/bbl in the first half of financial year 2020. They were down by around –5 per cent from the average of the prior half.

The front–month Brent minus WTI spread was materially narrower half–on–half, contracting to $5.57/bbl from $8.50/bbl. The WTI minus MARS18 spread averaged around –$2/bbl in the first half of the 2020 financial year (i.e. MARS at a premium to WTI), reflecting the impact of the tight market for sour crudes post the Venezuelan collapse and loss of Iranian barrels due to US sanctions. In calendar year 2017, in an “undistorted” operating environment, this spread was +$1.19/bbl.

In addition to traditional sources of price volatility, trade policy uncertainty has emerged as a powerful influence on investor sentiment towards oil. The Covid–19 outbreak has also impacted prices – and with good cause. We estimate that a net annual demand loss of around –0.2 Mbpd of crude will occur as a result of the outbreak: a number that could rise if our base assumption of containment within the March quarter is too sanguine.19

At the beginning of the 2019 calendar year we assessed that the fair value range for Brent in the coming 12 months was approximately $60/bbl to $75/bbl, –$5 lower at both ends of the range than in the prior year. In that framework, any movement below $60/bbl was likely to reflect a macro sentiment discount attributable to the trade war. That turned out to be a useful starting point for assessing the development of the market. With the trade impact neutralized for now, unfortunately Covid–19 has provided an equally plausible justification for prices to languish below fundamental fair value.

Oil demand has closely followed the broader trend in economic activity, in both global and regional terms. The strong and broad–based uplift of calendar year 2017 progressively gave way to a patchy regional picture in calendar year 2018. This then led into the very unbalanced picture in calendar year 2019. Solid growth in the US and China stood in contrast to weakness in Europe and developed Asia, and a softer performance from India and other major developing regions.

Despite the softening demand profile, the liquids market ended calendar year 2019 roughly balanced, with just +0.1 Mbpd added to supply over the year. Going forward we expect small stock builds of around +0.2 to +0.5 Mbpd in both 2020 and 2021, with a net increase in supply of +1.2 Mbpd and +1.5 Mbpd, respectively, assumed for the two years. The –0.2 Mbpd demand impact of Covid–19 referenced above is incorporated into these projected figures: as is a countervailing effort by OPEC+. Within calendar year 2020, we anticipate OPEC liquids output being reduced by a further –0.7 Mbpd, with other producers, led by the US, Brazil, Guyana and Norway, adding a combined +2.0 Mbpd.

US liquids production remains a key source of short term uncertainty. Our central case projects US supply to increase by around +1.1 Mbpd in calendar year 2020 (+0.7 Mbpd crude), down by –1.1 Mbpd from the spectacular +2.2 Mbpd run rate seen in calendar 2018 and –0.5 Mbpd below the almost as impressive follow–up +1.6 Mbpd (+1.3 Mbpd crude) seen in calendar year 2019. This outcome is eminently achievable based on the opening of take–away infrastructure in the previously constrained Permian and the very large inventory of DUCs (Drilled but Uncompleted Wells).

Investment in upstream oil was expected to increase by around 6 per cent in nominal terms in calendar year 2019, according to the IEA. That follows a 4 per cent increase in 2017 and a 6 per cent gain in 2018. The value of investment remains around 40 per cent lower than at the nominal peak in 2014, or –16 per cent lower at constant 2018 costs. US shale has increased its share of nominal upstream investment by a further five percentage points, primarily at the expense of offshore conventional. A little more than half of the growth in shale spending had been due to rising costs in the prior two years – but cost inflation has been less of a factor in very recent history.

We note with interest that the earnings reports of major oil field services companies have been noting a dichotomy between softening US onshore revenues and rising international revenues for about a year now – a reversal of the trend seen in the first two and a half years of the recovery.

In the long–term, we continue to see compelling market fundamentals, underpinned by a steepening cost curve underpinned by natural field decline.

We expect oil demand to grow by approximately 1 per cent per year on average over the next decade, despite significant efficiency gains in the light–duty vehicle fleet. Our long run view on electric vehicles (EVs) is discussed below and is available in more detail here as part of our electrification of transport series. Resilient demand growth from harder–to–abate sectors such as heavy duty trucks, non–road transport and petrochemical production will underpin an upward grind in overall barrels in the 2020s.

On the supply side of the market, with natural supply decline of at least –3 per cent per year added to the demand growth referenced above, by 2030 we see the need for new production equivalent to at least one–third of total global production today. We anticipate US tight oil production starting to plateau in the mid–2020s, at which point its role in setting global oil prices would begin to diminish.20 That observation, the industry’s relative lack of exploration success in the last half decade21 and the weak investment in the conventional sphere in recent years, points to the need for known but more costly supply to be induced to fill the long run gap to demand.

By the mid–2020s, the marginal barrel is expected to come from a higher–cost non–OPEC deepwater asset.

Looking beyond the 2020s, on the demand side we see an expected peak in the mid–2030s in our central case followed by a sedate trend decline. The annual loss of demand is not expected to approach the rate of systematic decline of existing fields, even based on a highly conservative estimate of the latter. Therefore, we expect that the industry will remain in a permanent state of inducement and reserve replacement even beyond the peak in demand.

Our low case for the oil price is predicated on OPEC running without discretionary spare capacity; high case EV penetration [well above the vast majority of published mid–cases]; trend increases in fuel efficiency in the traditional fleet; low case macro inputs constraining non–transport demand; a conservative weighted global decline rate assumption of –3 per cent; and a demand peak in the mid–2020s, a full decade ahead of the central case.

Back to top ↑

Liquified natural gas (LNG)

The Japan–Korea Marker (JKM) price for LNG averaged $5.20/MMbtu DES Japan in the first half of 2020 financial year, more than –10 per cent lower than the prior half, with the price ranging from $4.10 to $7.00/MMbtu. Prices were weighed down by large increments of new supply coming on–line just as Asian demand growth was pausing for breath after the frenetic expansion of the two prior years. That put the onus on Europe to absorb the excess cargoes, which in turn led to a material increase in the utilisation of European storage in advance of and through the northern winter.

Beyond the reporting period, against the backdrop of the Covid–19 situation, the forward curve has been pricing shoulder season JKM close to $3/MMBtu. It is important to note that this is not necessarily where all producers and consumers will transact. The majority of LNG molecules still change hands under long term oil linked contracts, although the proportion has been declining in recent years.

Looking ahead, within our generally constructive outlook for LNG demand growth the key uncertainties are Chinese energy mix policies and the scale of competing supply of indigenous and pipeline gas; the level of investment in new gas infrastructure in India; the timing and scale of nuclear restarts in Japan and energy mix policies in South Korea. Outside Asia, the amount of Russian pipeline gas supplied to Europe also represents a swing factor for the outlook.

On the supply side, a large increment of new production came to market in calendar year 2019, with an overflow from incomplete ramp–ups expected to influence fundamentals in 2020. That will add to the already large pipeline of projects where first gas is anticipated in calendar 2020. Similar to the impact of the 2019 overflow on 2020, 2020 ramp–ups are expected to have a substantial shadow effect on 2021, in our view.

Despite the strong LNG demand growth that we project for the medium–term, current and committed capacity is likely to supply the market fully until the middle of next decade, with considerable overflow from Asia to Europe expected at times. Beyond the mid–2020s new projects will be required in a global gas market where the marginal supply looks likely to come from North American LNG exports under a range of scenarios.

Four of the five new projects that produced first gas in calendar year 2019 were US export facilities; as are four of the six projects due to come online in calendar 2020. With US supply able to swing between the two major consumer markets of Europe and Asia, thereby drawing them closer together, a greater US export presence is a supportive signpost for the hypothesis that regional gas markets are on a path to harmonisation around a global benchmark.

We also note that a major push to increase the LNG trade could theoretically make a contribution to the fulfilment of China’s US energy purchase commitments under the Phase One trade deal. We say “theoretically”, as commercially it makes more sense for Chinese importers to take advantage of current JKM pricing, against which US cargoes are extremely uncompetitive.

In the longer term, we see LNG as a commodity that has an opportunity to operate under inducement economics, at times, given the combination of systematic base decline and an attractive demand trajectory. Global gas is also a big market that is getting bigger, with the LNG segment expected to almost double its share of that pie. However, gas resource is abundant and liquefaction infrastructure comes with large upfront costs and extended pay backs. To review how we resolve this complicated attractiveness equation, please click here.

Our low case for the LNG price is predicated on Qatar executing a market share strategy via the accelerated development of its North Field; Russian pipelines into Europe increasing market share by five percentage points; a low case macro environment curbing industrial and power demand; a ‘low carbon’ case for renewables penetration competing with gas in the power sector; and a cluster of optimistic FIDs by ‘portfolio players’; all of which serves to delay market balance by one full development cycle [from our central case timing of circa 2025].

Back to top ↑

Eastern Australian gas

The East Australian natural gas market continues to evolve. The start–up of Queensland LNG projects in recent years has irrevocably altered the fundamentals of domestic price formation. Our firm assessment is that the market will ultimately harmonise around an LNG benchmark. The likelihood of LNG imports being required as a seasonal source of incremental supply in the southern states has increased. This development would accelerate the harmonisation process, as would improving the transparency and depth of domestic price discovery mechanisms.

The tightness that had characterised the domestic market over the course of the 2019 financial year has been alleviated somewhat in the first half of financial year 2020. The combination of lower international spot LNG prices and Queensland LNG producers making more gas available to the domestic market put downward pressure on prices. This flowed through to lower power generation costs, as described elsewhere in this blog.

Looking beyond the temporary operating conditions seen over the last six months or so, whilst there is an ample resource base to meet long term domestic demand, the future cost to extract and process this resource appears to be rising. Further, constraints on onshore development hinder the efficiency with which the industry might otherwise operate. As traditional sources of supply fall off or plateau, new upstream investment will be required. To accommodate timely investment in competitive incremental supply, a clear and stable policy foundation is required.

We continue to believe that a more accommodative policy environment for onshore gas development – both conventional and unconventional – has the capacity to provide significant additional supply to the market at reasonable cost. Such an approach should help to encourage the new investment necessary to provide for reliable and affordable gas supply over the long term. It also has the clear benefit of allowing market forces to allocate capital where it will be most effective in achieving those ends.

Back to top ↑

Australian power market

A wave of new renewable capacity has entered the National Electricity Market (NEM) with Australia adding adequate capacity to meet the Large–scale Renewable Energy Target of 33TWh. This has arguably put the power sector on track to meet its share of Australia’s Paris emissions reduction target for 2030. Consequently, the Australian Government is focusing less on grid decarbonisation and more on improving the affordability and reliability of supply. Both these aspects of the NEM presently fall short of the levels required to ensure Australia’s international competitiveness or meet household and wholesale customer expectations. While the first half of calendar year 2019 had record high spot prices due to supply shortfalls, the second half was a different story. Subdued fuel costs and increased renewable generation resulted in a –10 per cent YoY price decline. Average power prices in the half were the lowest since calendar year 2016.

The relief felt by power consumers in the half year just completed may unfortunately be temporary. The ageing thermal generation fleet remains a source of concern with respect to NEM reliability. Projected generator retirements point towards a phase of heightened volatility in price and supply in the first half of this decade, especially during seasonal demand peaks.

The events of the most recent summer, when severe bush fires temporarily disconnected the New South Wales–Victoria interconnector, highlighted the inherent vulnerability of an inter–state transmission network with little inbuilt slack to cope with extreme circumstances. Further learnings from this episode are the need for both more dispersed generation and greater system integration. In this regard, we welcome the very recent announcement that a New South Wales–South Australia interconnector has received regulatory endorsement. The new interconnector is expected to be commissioned in the 2023 to 2025 (June financial year) window.

Due to falling technology costs and consumer preferences, it is likely that the NEM will continue to decarbonise, with or without government direction. We welcome both the Retailer Reliability Obligation, which has been written into law, to maintain adequate levels of system reliability and AEMO’s Integrated System Plan, which identifies future pathways for the National Electricity Market, taking into account policy objectives and market uncertainties. Further affordability and reliability gains are also possible if State and Federal governments are able to provide the policy confidence necessary to reduce the risk of investment in new dispatchable capacity, while meeting overall emissions reduction objectives in the market.

Longer–term, we expect total primary energy derived from coal (power and non–power) to expand at a compound rate slower than that of global population growth.

Energy coal

Energy coal prices were in a steady downtrend for most of the first half of financial year 2020.

The gcNewc 6000 kcal/kg FOB Newcastle index averaged around $68/t over the half, down from around $88/t in the second half of financial 2019. Prices ranged from a high of around $77/t to a low of around $62/t. The 5500kcal index averaged around $50/t over the same period, with a high of around $53/t and a low of around $48/t.

The spread between the spot indexes for gcNewc 6000 and 5500 averaged almost 30 per cent in the 2019 calendar year. The spread has remained at a broadly similar level since 2018, exhibiting resilience to the decline in base prices.

Chinese demand for seaborne energy coal increased in calendar 2019, despite modest industrial demand for power and a clear uplift in hydro generation in the first half of the year. The market consensus was that the 281Mt inflow registered in calendar year 2018 would serve as an informal objective for total coal imports (including metallurgical and lignite) in calendar 2019. While that may have been true at a point in time, the reality is that total coal imports in calendar 2019 were around 300Mt, comfortably surpassing the 281 Mt of the prior year and the 271 Mt of the year before that.

Contrary to the recent story in metallurgical coal, India saw strong growth in energy coal imports in calendar 2019 (+12 per cent YoY). The extended monsoon period22 resulted in an underwhelming performance by domestic supply (–1 per cent YoY in calendar 2019).

Demand from the Atlantic and Mediterranean regions has been weak. In part, this reflects commercially driven coal–to–gas switching in parts of Europe, where relatively cheap pipeline gas and LNG imports, plus a steep rise in the price of European Carbon Allowances23, have driven generator behaviour. The UK, Spanish and Italian markets were particularly soft. The recession in the Turkish economy has also had an impact on seaborne energy coal demand, with imports declining an estimated –2 per cent YoY in the calendar year–to–November. These trends were reflected in declining export volumes out of the United States and Colombia, the natural seaborne suppliers for these regions.

Longer–term, we expect total primary energy derived from coal (power and non–power) to expand at a compound rate slower than that of global population growth. Coal power is expected to progressively lose competitiveness to renewables on a new build basis in the developed world and in China. On a conservative estimate, the cross over point should have occurred in these major markets by the end of next decade. However, coal power is expected to retain competitiveness in India, (where the coal fleet is only around 10 years old on average), and other populous, low income emerging markets, for a much longer time.

Back to top ↑

Potash

Muriate–of–potash (MOP) prices24 have receded in recent months, ending a slow–but–steady rally dating back to mid–calendar year 2016. Brazilian gMOP25 prices, which had been trading at a premium to other major regional benchmarks for some time, have fallen the most. They are down nearly –$80 YoY to $270–280/t CFR as of December 2019. India has agreed a –$10 reduction to $280/t CFR for imports through March 2020. No such settlement has been reached with Chinese buyers. In December 2019, the FOB standard grade Vancouver benchmark midpoint was down by around –9 per cent YoY to $248/t. In the September quarter of 2019, Canada’s Nutrien reported a decline in its quarterly average realised price for the first time in three years, declining by –11 per cent from the previous release to $218 ex–mine. This figure is still up 3 per cent YoY (+$6) and +$68 (or 45 per cent) since the same period in 2016.

Global shipments rose +10 per cent YoY in calendar year 2017 to 67Mt. Shipments held at that record level in calendar 2018. For calendar 2019, the preliminary trade data suggest that shipments declined by –1 to –2 Mt. Headwinds for demand included a very wet spring in the United States, a late onset of the monsoon in India and weak palm oil prices hitting farm incomes in Southeast Asia.

The last three years are a microcosm of the history of potash demand. While trend growth in demand is quite reliable over longer time periods, one cannot rely on any particular year exhibiting trend–like growth.

Turning to the major consumption regions, China suspended MOP purchases on September 1st awaiting a new contract price (although volumes continue to arrive into bonded warehouses). Ahead of this action, China had bought very heavily: imports into China (Jan–Nov) were up 31 per cent YoY. Brazil’s import volumes (Jan–Nov) slowed after a very strong start to the year, eventually ending the period up 4 per cent YoY. India’s imports (Jan–Sep) were unchanged from the prior year. We had suspected that with a decline in import affordability, India would be one of the softer regions in calendar year 2019. Southeast Asia was the weakest performer among major markets: Indonesia (Jan–Sep) and Malaysia (Jan–Sep) saw imports decline –12 per cent YoY and –29 per cent YoY respectively.27

Canadian producers have borne the brunt of the weakening of demand, with exports (Jan–Oct) down –8 per cent YoY. Exports from Belarus (Jan–Oct) edged slightly lower, while exports from Russia were reportedly up by 8 per cent.28 The introduction of substantial capacity additions in Canada and Russia has for some time threatened to snuff out the potash price rally that dated back to 2016. In the end, ramp–ups have not been smooth and projects have been progressively pushed back. That meant that it was stuttering demand in calendar 2019 that ultimately brought the rally to an end.

As demand weakness spread from the Americas to Asia in the second half of the calendar year, the members of Canpotex announced further measures to curtail production. Similar announcements came from many other major producers, including the two eastern European giants, Uralkali and Belaruskali. The cutbacks, which amount to some 3 Mt in aggregate, while not a complete success if the yard stick applied is a lift in prices, at least appear to have limited the degree of price losses for producers – outside Brazil at least. The industry also appears to be relatively confident of a demand rebound in calendar year 2020.29

On the supply side of the industry, there are two greenfield mines under construction in Belarus, one due to be commissioned in the coming months, and the second planned for calendar year 2021. However, EuroChem has pushed back commercial production at its Volgakaliy project to 2020, while Uralkali is slowing down construction of two replacement mines until the mid–2020s. Meanwhile, Russian fertiliser manufacturer Acron has announced debt financing to complete its 2Mtpa Talitsky project, nearby Uralkali’s operations.

Turning to the long–term, demand for potash stands to benefit from the intersection of a number of global megatrends: rising population, changing diets and the need for the sustainable intensification of agriculture. We anticipate trend demand growth of 1.5 to 2.0 Mt per year (between 2 and 3 per cent per annum) through the 2020s. The pace of demand growth is important, because the need for new supply to be induced will only arise once both the spare capacity held by incumbents and capacity additions that are under construction have been absorbed by the market.

Our low case for potash is predicated on all presently latent capacity returning to the market at disruptive speed; considerable brownfield and greenfield additions coming to market; a low case macro environment curbing both opex and capex costs; ‘cheap’ currencies in major producer jurisdictions; a five percentage lift in crop residue recycling; minimal dietary change and crop mix; and a similar end–state for soil K mining to what is observed today. All of which serves to delay market balance and the onset of inducement pricing to well beyond the 2020s.

Back to top ↑

Nickel

Nickel prices ranged from $12,025/t to $18,625/t over the first half of the financial year, averaging $15,495/t. The major influence on price for much of the period was uncertainty about the direction and impact of Indonesia’s nickel ore export policies.

Firstly, there was uncertainty whether the timing of the ban would be brought forward, and if so, how abruptly. And once there was clarity on the first point, it was uncertain how exports might be policed in the period between the announcement in September 2019 and the inception of the ban in January 2020. Third, it was uncertain to what extent the ban, once enacted, would disrupt the various value chains that emanate from mined nickel ore in calendar 2020 and beyond.

Prices were understandably volatile against this backdrop – and other fundamentals were not standing still either. The 2020 calendar year opens with large precautionary nickel ore stocks at Chinese ports as the result of a sprint to procure supply in advance of the ban. There is also a sizeable build–up of finished stainless steel stocks sitting with Chinese producers. Clearing both stock positions will take time. The impact of the Covid–19 outbreak is expected to delay the re–start of the stainless steel consuming end–use sectors that would ordinarily consume the finished stocks; and while those stocks are abundant, nickel pig iron (NPI) producers have little incentive to run at high utilisation rates.

An additional factor to consider for the year ahead is that the structural implication of the Indonesian ore export ban is that the archipelago will become the world’s clear #1 producer of NPI essentially “overnight”, displacing China, and dramatically reshaping industry trade flows.

Nickel “first–use” is dominated by the stainless steel sector. It comprises more than two–thirds of primary demand today. Nevertheless, with a rapid and prolonged drive towards the electrification of transport in prospect, we contend that there are plausible long run paths where batteries and stainless steel will become equally important consumers of nickel, in a much bigger global market.