16 August 2022

Please refer to the Important Notice at the end of this article

Six months ago1, at the time of our half year results for the 2022 financial year, writing days before Russian troops had entered Ukraine, we stated that “the shared, albeit staggered recovery pattern of the prior half has given way to highly idiosyncratic trends within the energy and non–ferrous commodity clusters, as well as within the steel making raw materials complex. Nevertheless, and extreme volatility notwithstanding, most of our major commodities are trading at prices that are close to, or above, our estimates of long–term equilibrium”. As we release full year results for the 2022 financial year today, both statements remain valid. Prices in general remain close to or above forward–looking estimates of equilibria, while differentiation across commodity clusters has increased.

Over the last five months, energy2, food and fertilizer markets have been dominated by the direct and indirect impacts of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Non–ferrous metals and the steel–making value chain have also been impacted by former Soviet Union (FSU) supply uncertainty, but China’s dynamic zero–Covid policy and the financial market turbulence that has emerged under escalating inflation, multi–region central bank tightening and recessionary speculation have been more influential. In parallel with these trends, global logistics and manufacturing bottlenecks that were evident prior to the invasion have improved modestly, labour markets are arguably even tighter, the Chinese authorities are attempting to stimulate their economy in contrast to the global trend towards tightening, and pent–up services demand is still being released, funded in part by the substantial savings pools accumulated over the pandemic.

The global economic outlook is significantly more complex and multi–faceted now than a year ago, as the above series of observations makes clear. Little is certain in the face of such complexity beyond the fact that the overall rate of economic growth will decelerate – ex–China – as the impact of global monetary tightening is progressively felt over the next 6–18 months.

Beyond the obvious directional trend, the degree of the slowdown is unclear. A recession in the United States and other developed markets is within the range of shorter–term possibilities that we consider. Our base case for calendar 2023 is that for the US, avoiding a sharp rise in involuntary unemployment – the key marker of a recession – is a manageable task. Europe on the other hand faces a more troubling constellation of negative factors, including sovereign debt risks as bond yields rise, as well as an energy crisis. In the developing world ex–China, tighter financial conditions alongside rising prices for food and fuel presage challenges – especially for those regions where depreciated exchange rates, high foreign debt and balance of payments challenges have led to a loss of monetary independence3.

In China itself, the picture is mixed, with both upside and downside risks to consider. On the downside, the possibility of further lockdowns interrupting growth cannot be counted out whilst there is an immunity gap in the population and the zero–Covid stratagem remains in place. Exports are also likely to slow. On the positive side, substantial policy support for growth has been put in place, dating back to late in calendar 2021, and this is already showing through in sectors like autos and infrastructure. As ever though, the test will be how the real estate sector responds. On balance, we feel confident enough to say that at a minimum China will be a source of stability over the coming year. And perhaps something much more than that if the supply side of the property industry is effectively de–bottlenecked.

See additional commentary on global economic growth here.

For the 12 months of financial 2023, we assess that weighted directional risks to annual average prices across our diversified portfolio are balanced or tilted modestly downwards, a view that relies in part on the lower starting point created by substantial price depreciation already observed in the financial year to date. These developments have highlighted the intrinsic vulnerability of “fly–up” pricing to modest improvements in supply conditions or material changes in demand conditions – whether actual or expected.

Beyond the slowdown in ex-China demand, the observed turn in the Chinese policy cycle, ongoing two-way uncertainty as to FSU trade flows, a range of operational challenges across key mining jurisdictions and the fact that operating cost curves have moved higher and steepened amid the global inflation shock, are all relevant considerations for thinking about how near–term prices might develop. Notably, industry–wide cost inflation has raised real–time price support well above pre–pandemic levels in many of the commodities in which we operate.

The lag effect of these inflationary pressures is expected to remain a challenge in the 2023 financial year, with labour market tightness and energy markets now edging ahead of manufacturing supply chain and logistics constraints as the most pressing forward–looking concerns.

We expect the supply–demand balance to move out of deficit in both copper and nickel, with supply conditions improving (more so in nickel) in both commodities just as demand in the ex–China world is coming off the boil (more so in copper) – and the ex–China slowdown is occurring before Chinese policy easing has fully delivered its intended impact.

Iron ore moved into a considerable surplus in the first half of financial year 2022, before tightening somewhat in the second half. On balance, it seems likely to be in surplus across financial 2023. On the supply side, that view assumes a stronger aggregate operational performance by the seaborne majors than we have observed in recent history, as well as a pick–up in the availability of ferrous scrap.

Metallurgical coal prices achieved all–time records in the second half of financial year 2022 on strong ex–China demand and multi–regional, multi–causal supply disruptions. These “fly–up” prices partially unravelled early in financial 2023, as some sources of disruption faded and ex–China steel markets softened noticeably in the face of broader macroeconomic headwinds. Chinese import policies remain a key uncertainty for both metallurgical and energy coal. The latter commodity also ascended to record highs in financial 2022, with supply constraints in the major export nodes coinciding with strong demand conditions. The balance is expected to remain tight at least through the forthcoming northern hemisphere winter, with energy security issues paramount.

Potash prices escalated rapidly in the second half of financial 2022 on the credible threat of outright physical scarcity. Strong farm economics coupled with the loss of shipments from Belarus and (to a lesser extent) Russia created the veritable perfect storm. The regional price structure at the close of financial 2022 is obviously susceptible to any sign of a return to more normal levels of total FSU exports. Even so, with crop prices also elevated, potash affordability, while stretched, is nowhere near as bad as it was at the peak of the last major price upswing.

Looking beyond the immediate picture to the medium term, we continue to see the need for additional supply, both new and replacement, to be induced across many of the sectors in which we operate.

After a multi–year period of adjustment in which demand rebalances and supply recalibrates to the unique circumstances created by COVID–19, the war in Ukraine, and the global inflationary shock, we anticipate that geologically higher–cost production will be required to enter the supply stack in our preferred growth commodities as the decade proceeds.

The projected secular steepening of some industry cost curves that we monitor, which may be amplified as resource nationalism, supply chain diversification and localisation, carbon pricing and other forms of “greenflation” (which we define below) become more influential themes in both demand and supply centres, can reasonably be expected to reward disciplined and sustainable owner–operators with higher quality assets featuring embedded, capital–efficient optionality.

We confidently state that the basic elements of our positive long–term view remain in place.

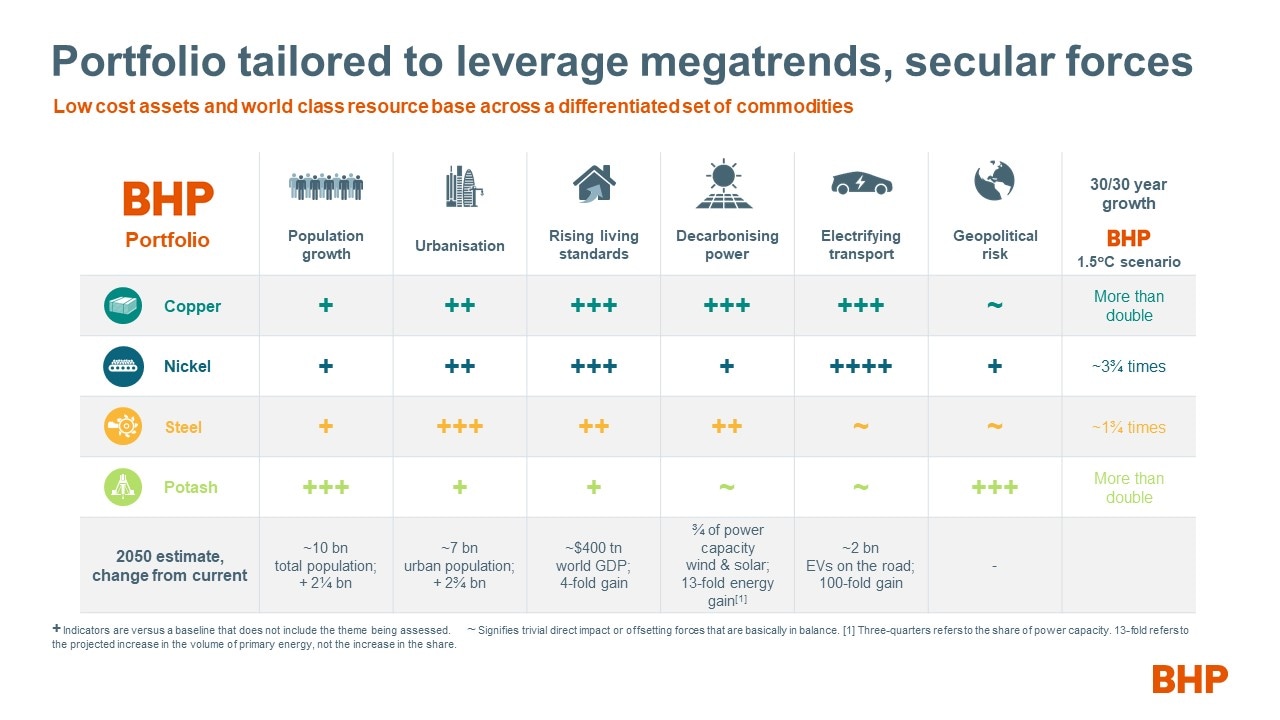

Population growth, urbanisation, the infrastructure of decarbonisation and rising living standards are all expected to drive demand for steel, non–ferrous metals, and fertilisers for decades to come. We continue to see emerging Asia as an opportunity rich region within a constructive global outlook.

From a pre–pandemic baseline, by 2030 we expect: global population4 to expand by 0.8 billion to 8.5 billion, urban population to also expand by 0.8 billion to 5.2 billion, nominal GDP to expand by $83 trillion to $ 171 trillion and capital spending to expand by $16 trillion to $39 trillion5. Each of these fundamental indicators of resource demand are expected to increase by more in absolute terms than they did across the 2010s.

By 2050, we project that: population will be approaching 10 billion; urban population will be approaching 7 billion; the nominal world economy will have expanded to around $400 trillion, with one–fifth of that – i.e., around $80 trillion – being capex.

In line with our purpose, we firmly believe that our industry needs to grow in order to support efforts to build a better, Paris–aligned world6.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) stated on August 9, 2021, that “Unless there are immediate and large–scale greenhouse gas emissions reductions, limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius will be beyond reach”. As illustrated by the scenario analysis in our Climate Change Report 2020 (available at bhp.com/climate), if the world takes the actions required to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees, we expect it to be advantageous for our portfolio as a whole7.

And it is not just us.

What is common across the 100 or so Paris–aligned pathways we have studied is that they simply cannot occur without an enormous uplift in the supply of critical minerals such as nickel and copper.

Our research also indicates that crude steel demand is likely to be a net beneficiary of deep decarbonisation, albeit not quite to the same degree as nickel and copper. And some of the scenarios we have studied, such as the International Energy Agency’s high–profile Net Zero Emissions scenario8, would be even more favourable for our future–facing non–ferrous metals than what is implied by our own work to date: albeit with different assumptions and potential impacts elsewhere in the commodity landscape.

We welcome the fact that the share of global emissions now covered by national level net zero or carbon neutral national ambitions has reached 85%, although we continue to monitor the pace at which these ambitions crystallise into tangible action9. Our key Asian customer centres of Japan and South Korea (2050), China (2060) and India (2070) are among the nations that now have carbon neutral commitments. Less positively, the share of global emissions that are “priced” has much lower coverage, at 23%, and the average price itself, at $26/t, is still too low to sponsor the radical change in the energy and land use system that is required if ambitions are to be met10.

Against this backdrop, “clean energy” investment, as defined and estimated by the IEA, is expected to reach $1.44 trillion in calendar 2022, a 10% increase from the prior year and about 40% higher than in 2015. Easier–to–abate sectors – renewable energy and electrified transport – are expected to attract $582 billion in calendar 2022, while complementary outlays on electricity networks, nuclear generation and energy storage were just short of $400 billion. A separate dataset from Bloomberg NEF shows that technologies with the potential to unlock gains in harder–to–abate corners of the energy system – Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS) and hydrogen – attracted just over $4 billion collectively in calendar 2021. The aggregate and sectoral figures are both promising (in terms of growth) and underwhelming (in terms of the gap between actual spending and the levels required to jolt the world onto a Paris–aligned pathway) at the same time.

As the true costs of a lack of climate action are progressively recognised, and demographic change proceeds, we anticipate that a popular mandate for closing the gap between ambition and policy action will progressively emerge.

Here we note that the younger generations that will define our future – both Millennials and Generation Z – are more concerned about climate change than their elders in both East and West. They are also more favourably disposed towards globalisation. That is good news for the international cooperation that will be required to limit global warming in the most efficient manner. And it also offers some hope that the current wave of economic nationalism that we observe – which represents a headwind for long term global prosperity regardless of whether the origin of that sentiment is political populism or geopolitical competition – may also retreat in time11.

Investment that seeks to abate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and/or adapt to, insure against, and mitigate the risks of climate change is expected to rise to become a material element of end–use demand for parts of our portfolio. The electrification of transport and the decarbonisation of stationary power are expected to progress rapidly, and the desire to tackle harder–to–abate emissions elsewhere in the energy, industrial and land–use systems is building. Comprehensive stewardship of the biosphere and ethical end–to–end supply chains will become even more important for earning and retaining community and investor trust12.

Now: add each of the generally constructive foregoing themes to the fact that the resources industry has been disciplined in its allocation of capital since the middle of the 2010s. With this disciplined historical supply backdrop as a starting point, any sustained demand surprise(s) to the upside seem likely to flow almost directly to tighter market balances.

That last observation should not be taken to imply that the industry will suddenly become exempt from the cycles that have characterised its history. Cyclical swings of considerable magnitude will continue to occur, in line with core fundamentals that sponsor volatility: fluctuating demand from traditional end–use sectors, very long lead times for project delivery and the lumpy nature of supply additions when they do occur. Even so, with the secular underpinnings of those commodities that are positively leveraged to the decarbonisation mega–trend so firm, the depth and duration of future cyclical price corrections might reasonably be expected to be shorter and shallower than some of those seen in the past, while upswings may prove more enduring.

Against that backdrop, we are confident we have the right assets in the right commodities in the right jurisdictions, with attractive optionality, with demand diversified by end–use sector and geography, allied to the right social value proposition.

Even so, we remain alert to opportunities to expand our suite of options in attractive commodities that will perform well in the world we face today, and will remain resilient to, or prosper in, the world we expect to face tomorrow.

Global economic growth

The world economy contracted around –3% in calendar year 2020 before bouncing back by a little less than +6% in calendar 2021. Calendar 2022 is on now on track for a modest outcome around 3½%. The global economy has been weighed down by China’s June quarter lockdowns, a softer than expected first half in the US, the wide–ranging impacts of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and aggressive central bank tightening ex–China in response to rapidly accelerating inflation. Our early take on world growth in calendar 2023 is +3¼%, with improvement in China offset by a wholesale softening elsewhere. The IMF’s latest projections for 2022 and 2023 are roughly –¼% and –½% below our forecasts, partially reflecting what we see as overly pessimistic projections of just 3.3% and 4.6% for China in calendar 2022 and 2023 respectively13. That said, China will have to avoid material lockdowns between now and the end of calendar 2023 to achieve our forecasts. If China is not able to do so, world GDP would likely be roughly –¼% lower in calendar 2023 than in the absence of new lockdowns.

Against this backdrop exchange rate volatility has picked up alongside rising interest rates and falling equity markets, after a surprisingly calm six months for currencies in the first half of financial year 2022. Compared to the levels prevailing at the time of our half–year results, the US dollar index (DXY) was roughly +8% stronger as financial year 2022 closed. In real trade weighted terms, as of June–2022 the US dollar has increased in value by roughly +4.4% from December–2021, and had surpassed the level reached in the COVID–19 panic of April–2020. US dollar strength was expressed broadly, with pronounced gains against both non–China emerging markets and the G3. USD/JPY approached levels not seen since the Asian Financial Crisis and EUR/USD traded towards parity: a level not breached from above since the Greenspan era Tech Bubble. The US dollar appreciated by a more modest +¾% against the Chinese yuan in the second half of financial 2022, or around +5% point–to–point.

International merchandise trade collapsed by around –5% in calendar 2020. The strong recovery from the nadir, which began in the second half of calendar 2020, has continued essentially unabated since, with calendar 2021 up around +10%, and calendar 2022 year–to–date tracking at +4.4%% YoY. Unit prices of world exports are up around +13% year–to–date, on top of a gain of +14.4% in calendar 2021.

As global policymakers increasingly focus their attention on cost–of–living concerns and the related questions of food and energy security, it is worth highlighting that the act of deepening trade integration tends to suppress inflation while the opposite action tends to amplify it. Trade is the essential lubricant of the global economy, and any agenda seeking to reinstate a healthier balance between growth and inflation ought to embrace that fact.

In addition, we strongly encourage policymakers to prioritise structural reforms at home as the surest route to sustainable productivity growth, and ultimately, prosperity. Remaining open to the cross–border flow of people, goods, capital, and ideas is vital to this end: unrestricted trade based on comparative advantage, competition, productivity and innovation and an affordable cost–of–living are close companions. Much of the “bad” inflation we have referred to frequently throughout this mini cycle is the direct or indirect result of natural cross border flows of physical production inputs and people being impaired. The sooner the logic of comparative advantage in international trade and entrepreneurial “pull” migration can again be granted full play, with due consideration for public health concerns of course, the better for both growth and inflation.

These arguments highlight the importance of continued and vocal advocacy for free trade, open markets, and high quality national and multilateral institutional design by corporations, governments, and civil society.

The global inflationary curve was steepening even before Russian troops entered Ukraine. We have been flagging an inflationary upswing since the second half of calendar 2020, noting an expected combination of strong demand, constrained supply elasticity in a range of goods–producing and distributing sectors, and the fact that normal movements of labour within and across countries to match with job opportunities has also been impaired.

As a result, productivity has suffered, market balances have tightened and, in some instances, scarcity pricing has emerged. These factors drove the underlying cost base of some of the world’s most essential end–to–end value chains sharply higher – for example petroleum products, construction materials, electronics, automobiles, and food – along with the associated distribution industries (principally land, sea, and air logistics).

And then came the invasion.

As of June 2022, consumer and producer prices in the US were tracking around +9% and +11% YoY respectively, with a modest decrease to 8.5% for CPI in July. The most recent updates on producer price inflation in the EU, Japan, China, and India are distinctly elevated at +30%, +9%, +6% and +15% YoY respectively (rounded). Major commodity producing countries such as Chile, Canada, Brazil, and Russia are seeing equivalent or even higher outcomes. Australia is presently at the lower end of the field with PPI at “just” +5.6% YoY and CPI at +6.1% YoY in the June quarter.

We anticipate that elements of the “bad” inflation created by known bottlenecks prior to the invasion of Ukraine will remain challenging in financial 2023: the lag effect of which may influence our business well into the following reporting period.

However, at the margin, improvement is evident in some important areas14. Indeed, some of the key value–chains referenced above – such as electronics and construction – are now exhibiting reduced supply chain pressure. The bad news is that this is not a pure productivity effect: supplier delivery times are still poor relative to normal, and the observed rundown of backlogs and the rise in value chain inventories has partially been due to the increase in macroeconomic uncertainty.

The sectors of most concern in terms of higher future inflationary pressure are those where labour availability and energy supply are the key constraints, rather than manufactured or basic material inputs. What we described as the “energy situation” six months ago is now a crisis.

This crisis has been sparked by the direct and indirect impacts of the Russian invasion, which has revealed some of the frailties of regional power and energy networks. The potential for further price spikes in energy commodities and power prices, as well as outright shortages and rationing, remain very real. Labour is a more complex question, with a mix of idiosyncratic local and common global factors at play.

We maintain our long–held view that “good” demand–led inflation, which is presently obscured amidst the tremendous difficulties of the here and now, will re–emerge and then endure for some time. This will contribute to higher average inflation outcomes across the 2020s than what we experienced across the 2010s – even after abstracting from the peak of calendar 2022.

Higher inflation on average across the decade will assist with the passive repair of strained public sector balance sheets. The extra 1 per cent on the average global inflation rate that we envisage for the 2020s will increase the size of the nominal global economy by around $18 trillion by 2030, or 21% of 2019 GDP15.

The phenomenon of secular “greenflation” is also a genuine force and will, we believe, impact upon price dynamics and the wider economy in the medium and long run. There is more than one definition of this concept in circulation, so let us be clear what we mean by this.

“Greenflation” is the process whereby the global price level progressively internalises the costs and benefits of both action and inaction pertaining to the impact of climate change and stewardship of the biosphere.

It is a fact that the global price level does not yet fully internalise the social cost of carbon, the emissions of other greenhouse gases (GHGs), other activity that negatively impacts upon natural wealth, such as deforestation and biodiversity loss, or degrades other eco–system services, or the future capex bill for governments and business to deliver on all aspects of the energy transition, from the provision of critical minerals to building the decarbonisation and climate change adaptation infrastructure of the future. To date, regions or individual actors with positive footprints also find it difficult to quantify, let alone monetise their virtue. The process of internalising these costs, and remunerating positive actions, whether the process be swift or gradual, will inevitably permeate the dynamics of price formation in all corners of the economy.

China

China’s economy has been nothing if not turbulent in the 2020s to date. First, we saw a spectacular V–shape across calendar 2020, with strong momentum carrying over into the first half of calendar 2021, giving China “first–in, first–out” status in the global pandemic. The positive momentum was then arrested – abruptly – in the September quarter of that calendar year. The “dual control” framework for energy policy, the “zero–growth” steel mandate and the desire to constrain macro–financial risks in the property market were all fierce headwinds for the growth trajectory. The reality of the resulting slowdown, the scale and pace of which was clearly unintended, soon had the authorities announcing a series of counter measures designed to stabilise confidence moving into an important political year in calendar 2022. Calendar 2022 started with promise, partly due to the tilt towards easier policy settings – but then came the COVID–19 lockdowns in the June quarter: a period in which the economy suffered a sequential contraction. Roughly two months into the recovery period from the lockdowns, the flow of data has been somewhat mixed.

A rapid turnaround between the last tightening measure of a cycle and the first easing measure of a new one is not unusual in China. The major uncertainty in such circumstances is how to gauge the appropriate lag between the change in policy stance and the response of real economic activity. Obviously, the blunt force of the lockdowns in the June quarter, and the omnipresent threat of snap civic restrictions that will persist while a material immunity gap in the population remains, complicate the analysis. So too does the present state of the all–important real estate sector.

China’s housing market has often been at the centre of counter–cyclical policy shifts. It is also the biggest wild card in the remainder of calendar 2022 and into calendar 2023. Our current diagnosis is that what ails Chinese housing is not a demand problem – it is a supply–side problem.

More specifically, the resolution of the current issue lies within the nexus of developer balance sheets, macro–prudential controls on the same, and risk–averse financiers, who have lost confidence over the last twelve months or so in the face of high–profile defaults.

It is instructive to compare the present situation to the extended real estate downturn of the mid–2010s. The earlier cycle was characterised by an excessive inventory of unsold properties, with substantial over–building in lower tier cities intersecting with tightening purchase controls on out–of–town investors against a backdrop of policy uncertainty under the anti–corruption drive, property tax pilots and the national housing ownership registry. Such was the depth of the issue that “housing de–stocking” that it became a macroeconomic priority in parallel with the execution of President Xi’s signature Supply Side Reform (hereafter SSR) initiative.

The excess inventory problem at the national level was also the collective expression of hundreds of demand–supply mismatches across China’s various city tiers. The resolution required a transfer of real assets from the balance sheet of developers to the balance sheet of households, and that in turn required an increase in purchasing power and regulatory forbearance on the out–of–town investor question. The transfer was ultimately unlocked through a considerable expansion of mortgage loans and a more lenient approach to investors.

The upswing began tentatively, with the average historical lag relationship between the leading indicators and building activity comfortably exceeded, but ultimately an enduring upswing in sales and starts was put in place. It had a lower peak but a longer tail than prior cycles. The shadow of this cycle is still visible in the pipeline of work under construction today – which is part of the problem. Developers have been incentivised to start multiple projects but not to complete them in timely fashion. This oddity stems from the fact that buyers need to compete for access to developments by paying very large down–payments – 100% up front – a practice that has evolved due to the extraordinarily high demand for property assets in China which has historically put developers in a very advantageous bargaining position. If they choose to, developers have been able to dawdle their way through projects after the initial phase without repercussion – prioritising the majority of their capital instead for the acquisition of land and the initiation of new projects.

The authorities have progressively recognized that this issue was creating unhealthy imbalances in the real estate market. For some years, the response was to tread relatively softly, reflecting the sector’s central role in employment, the credit–collateral system, and the storing of wealth. National level housing policies have been directed towards limiting speculation, modest direct interventions via public housing and shanty town reconstruction and the building up of rental markets. These measures did not tackle the root causes of the starts/completion imbalance, one of which was of course the incentive matrix faced by developers. The enormous wedge between the volume of starts and completions that opened across 2016–2019 made this abundantly clear. The response was to place developers into a traditional SSR template, with specific macro–prudential guardrails now known as the “three red lines” introduced in August 202016.

These regulations, finally, increased the incentive for leveraged developers to complete projects in timely fashion, as running down their liabilities to off–the–plan buyers counts towards the –10 percentage point reduction in the liability–to–assets ratios required of the sector. This has seen completions out–perform starts. But with most of the sector coming under financing pressure since Evergrande’s problems came to light roughly a year ago, even working capital has become an issue for some developers. That has led to a very slow supply response to the easier policy measures enacted to boost the demand side of the housing market; a distinct lack of progress on many semi–finished projects; and disgruntled purchasers in multiple locations threatening mortgage servicing strikes.

This latter factor may have been the final straw that forced the authorities’ hand to intervene directly on the supply–side. Not long after this story created a local media stir, it was made known that a state–backed vehicle would be created to backstop financially distressed developers and get liquidity flowing to the sector again. The Politburo meeting of late July released some high–level details, alongside a resolute statement to “stabilise the real estate market” and “ensure housing delivery”.

This episode shows yet again that at this stage of China’s development, real estate is so significant in terms of its impact on employment, local government finances and consumer confidence, not to mention the backward linkages into heavy industry, that anything more than a shallow dip is difficult to absorb whilst also retaining desired levels of macro stability.

Turning to the specifics now, this is how the major housing data stood as of June 2022 (year–to–date, YoY unless otherwise stated). The volume of housing starts – the key indicator for contemporaneous steel use in real estate – have declined by –34.4%. Sales volumes declined –22.2% (weighed down by pre–sales at –27%: existing home sales rose +16%). The equivalent comparisons for housing completions – the key indicator for contemporaneous copper use in real estate – was –21.5%. Floor space under–construction was tracking at –2.8%; land area sold was –48.3% YoY and developer financing was –25.3%.

A final observation on housing: the scaled inventory of unsold dwellings is close to historical lows as we move into this next cycle phase. A sustained period of weak starts has diminished the pipeline of work, and the needed focus on completions has been delayed. That implies that despite the challenges on the supply side of the industry, risks for housing prices are not skewed downwards. In fact, the reverse may well be true.

Prior to the imposition of growth suppressing policies in the September quarter of 2021, when the policy stance in China could still readily be described as accommodative, we argued that while in an absolute sense China has made a considerable effort to support jobs through the pandemic, in a relative sense, policymakers have not over stimulated. That judgement gauges the Chinese response versus developed countries during the pandemic, and relative to its own actions in response to the GFC.

That case can still be made. For one thing, alone among the major economies and despite its very large exposure to imported commodities, China does not have an economy wide inflation problem. Even so, there is also a case to be made that the increasing urgency to spur activity towards the 5.5% GDP for calendar 202217, even as the June quarter lockdowns made that very unlikely, means that a considerable amount of additional policy support is sitting in the system waiting to unfurl (to the degree that the zero–COVID mandate permits). Policymakers the world over are highly susceptible to this kind of mistake – a failure of patience. Policy packages are generally well calibrated in their first iteration. But then comes the gnawing doubt – the slow wait for confirmatory data, the worry about leads and lags, and the temptation to do a little more before you have any genuine evidence of the impact of the first wave. Just as there is a case for an underwhelming performance over the next 6–12 months should the real estate sector fail to bounce despite pervasive encouragement to do so, there is also an upside case where real estate moves into a clear recovery phase and it turns out that the non–housing sectors have been over–stimulated. Food for thought. Our P50 case sits between these two bookends.

Moving on to those non–housing end–use sectors now, and fixed investment in infrastructure has emerged as a bright spot in calendar 2022 to date, as expected, with 9.2% growth June year–to–date, YoY, and 12% YoY in the month of June itself. This pick–up has been financed by aggressive front–loading of local government bond issuance.

The overall infrastructure sector has had a mediocre run over recent years, with annual growth for every year from 2018 to 2021 falling between 0.2% and 3.4%. The subsector that has most obviously held infrastructure back prior to the current year is water conservancy and related areas, where spending had expanded at a two–year compound growth rate of just +2% at the time of our half–year results six months ago, despite periodic entreaties from Premier Li for local governments to boost outlays in this area. At roughly 40% of spending in the broad infrastructure category (yes, it is larger than either transport or power generation), this uplift is impactful for overall end–use demand trends. Elsewhere in the infrastructure space, in the month of June power outlays were tracking at a strong 24% YoY [led by renewables, as discussed in more depth in the copper chapter] while transport was at around -1.2%.

For auto production, this is what we wrote six months ago: “For calendar 2022, we see stronger outcomes for conventional production, with value chain supply constraints progressively clearing. This may be evident in the first half: but if not, certainly by the second.” The reality is that lockdowns made things difficult for a time, but the introduction of time–limited tax incentives for buyers (June–2022 to December–2022) saw sales jump sharply in the month of June. As for New Energy Vehicles (NEVs), they continue to leapfrog the most bullish of expectations, with China experiencing triple digit percentage growth in production and sales in the first half of calendar 2022 after 168% growth in 2021.

Elsewhere in the domestic end–use story, machinery has come back to earth after a very strong run up in recent years, with transport, construction and agricultural machinery all weakening in the year–to–date. Power machinery has been resilient within the broader category slowdown. The overall segment is –5% YTD YoY as of June. Consumer durables have been a little firmer than machinery in the domestic market, but they have seen export markets tailing off.

Exports increased by around 30% in calendar 2021, and somewhat against expectations managed to expand rapidly again in the first half of calendar 2022 (+14.2% YTD YoY, +18% YoY in July itself) despite that high base and ongoing tariff protection in the US. Chinese manufacturers have been arguably the leading beneficiaries of the global boom in goods consumption observed over the last two years or so, gaining around 2 percentage points of global market share (from around 13% to around 15%)18.

The data implies strongly that claims of the demise of the Chinese manufacturing export machine have been greatly exaggerated.

There are of course some special or short-term cyclical factors behind this on-going strength that will unwind in due course: (1) The global boom in consumer durables (including IT hardware for WFH), played to China's existing strengths. Latest data shows this has topped out. (2) The invasion of Ukraine has created some extra space for Chinese exporters to fill, for instance in steel and other metals. (Steel and aluminium exports up 18% and 39% YoY respectively in July).

Balancing that, the latest data show an emerging source of secular strength beginning to come through: China is the major manufacturer of the decarbonisation hardware that the world needs to meet its climate goals. In July-2022, exports of EVs rose +151%, solar panels +15% YoY, and wind turbines 58%, YoY YTD).

Major economies are increasingly buying into the doctrine that decarbonisation and energy security go together, and that should extend to the manufacturing and critical minerals supply chains that support them. China made this strategic connection some time ago, established an industrial policy framework and has invested heavily and consistently on the manufacturing side. That consistency has enabled Chinese firms to achieve a strong incumbent position in the manufacture of backbone green technologies such as solar cell modules, EV batteries, hydrogen electrolysers and wind turbines, and the processing of critical minerals.

Staying with the longer-term, our view remains that China’s economic growth rate should moderate as the working age population falls (noting new estimates from the UN released on July 11th indicate that the total population is peaking now – rather than around 2030 as in the previous vintage) and the capital stock matures. China’s broad production structure is expected to continue to rebalance from industry to services and its expenditure drivers are likely to shift from investment and exports towards consumption, with late–stage urbanisation a complementary element in this shift.

Nevertheless, even as percentage rates of growth slow down, and the structure of the economy evolves, China is expected to remain the largest incremental volume contributor to global industrial value–added and fixed investment activity through the 2020s and likely well beyond.

Within industry, we expect a concerted move up the manufacturing value–chain, in addition to a marked shift in the nation’s energy system as it positions to meet decarbonisation objectives. This will require considerable further improvements in the domestic innovation complex as the transfer of foreign technology is not expected to be as straightforward as it was earlier in China’s development drive. Notwithstanding the emphasis now being placed on the more introspective thematics of “dual circulation” and “common prosperity”19 , we anticipate that the concerted move outwards of the 2010s is likely to continue, with an emphasis on South–South cooperation, regional trade agreements20, and the Belt–and–Road corridors, with China seeking both markets and resources in these ongoing endeavours. More broadly, we anticipate environmental concerns will become an even more important consideration in future domestic and foreign policy design than they are today. Within this context, China’s plans to see a carbon dioxide emissions peak in advance of 2030 looks readily achievable, while hitting its 2060 carbon neutrality objective is a considerably more challenging task.

Major advanced economies

The US economic outlook is delicately poised.

Six months ago, we stated that: “… some aspects of the global inflation spike are almost certain to be transitory. Even so, in the US there are genuine fundamentals tailwinds for growth and employment – and by extension inflation – due to the robust strength of the real economy. These tailwinds feel as if they could persist for some time, with or without further impetus from fiscal policy.”

Many of those tailwinds are still in evidence – as will be discussed below. But major headwinds for growth have emerged since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, with the nexus of rising inflation, rising interest rates, and falling equity markets hurting both business and consumer confidence and denting the interest rate sensitive (and previously booming) housing market. Against this backdrop, the practical application of the Fed’s new average inflation targeting framework is undergoing a very stern test, with headline consumer price inflation reaching 9.1% in the month of June, having held above 7% through the first half of calendar 2022. Fed rhetoric has shifted from modest unease as calendar 2021 closed to doing “whatever it takes” in calendar 2022. That approach has lit a fire under the US dollar.

Countering the proximate reasons for pessimism listed above are the ongoing presence of tailwinds. The list of potentially positive factors for the outlook includes (1) the very large household cash saving pools accumulated during the pandemic (2) considerable wealth accumulation besides [albeit financial asset prices have now corrected abruptly and wiped out some of this gain] (3) the tight labour market that is producing strong growth in jobs and nominal labour income, especially for households where marginal propensities to consume are high21 (4) the solid capex outlook as companies and all levels of government continue to play catch–up on three fronts – (a) in traditional capital stock after the relative neglect of the 2010s, (b) to accelerate decarbonisation efforts, (c) to accelerate digitisation and automation efforts to confront the pressing concern of labour shortages, and (5) the further release of pent–up household demand for discretionary services.

That is quite a list. Even so, with house building no longer on it, and the major headwinds blowing at gale force, realistically they can only be a partial offset. Much now depends on when the Fed decides to pause and survey the landscape. That in turn depends upon the month-by-month inflationary trajectory and what it tells us about calendar 2023.

First things first, if the global economy does slow down considerably, substantial pressure will be removed from supply chains, and that will flow into a weaker inflationary pulse in non–energy raw materials and (some) durable goods relatively promptly. There was arguably a preview of that in the July US CPI outcome. Wages though move more slowly and are a critical factor in any medium–term forecast of aggregate inflationary pressures in services, which dominate inflation index weights. Six months ago, we argued the following: “Even with the recent acceleration, we note that wage inflation is still lower than in the late 1990s boom, when a “job switcher” received an average change of around 6%, versus CPI inflation around 2%. US CPI is currently sitting around 7%, which means even a job switcher is presently underwater vis–à–vis the average cost–of–living. And with labour force participation still well below pre–pandemic levels as of June–2022 (63.4% versus 62.2%), this story feels like it is a long way from its conclusion.” In this regard, we note that wage increases for those changing jobs have accelerated to 6.4% YoY, and wage outcomes for those staying in jobs are also on the move (4.7% YoY). The preceding figures are 12 month moving averages. The 3 month moving averages are more dramatic at 7.9% (switcher) and 6.1% (stayer)22.

Will the slowing economy crack the labour market? The unemployment rate is presently 3.6% and the participation rate is unchanged from six months ago at 62.2%. Total employment has reclaimed its pre–pandemic level (just), but the economy is almost 15% (or $3.2 trillion) larger. The Richmond and Atlanta Fed’s joint June quarter CFO survey indicated that “labour quality and availability” is the single most pressing concern for the C–suite, overtaking inflation, with more than 11 million job vacancies across the nation, while “quits” and “layoffs” are still running around all–time highs and all–time lows respectively. Labour availability was cited three times more frequently than the health of the economy as a pressing concern by these survey respondents. Once again, the refrain that this story feels like it is a long way from its conclusion still seems apt.

Closing out this line of argument, we note that the fact that the US economy has already contracted in real terms across the first half of calendar 2022. This has opened a Pandora's Box of technical (and mainstream and social media) debate as to whether this means that the US is already in recession. The first point in this regard is that a recession officially occurs when the National Bureau of Economic Research’s (the NBER) “Business Cycle Dating Committee” says so, and the NBER takes a much broader view than the GDP figures alone. Our view is that until the unemployment rate increases in a material way, claims of a recession and the pronounced and widespread economic hardship that term entails, are misplaced. Jobs are still growing nicely, thank you very much, with non-farm payrolls expanding by +528k as recently as July-2022. You grow the economy to create income and jobs, and the US has been doing precisely that – GDP is not an end in itself.

In the wake of the Biden inauguration, eighteen months ago we wrote that “The Biden administration is a pivotal one in global history:

- It has the potential to rapidly accelerate global decarbonisation trends.

- It faces monumental geopolitical choices, both in terms of its approach towards multilateralism and its attitude towards key bilateral relationships.

- It has the potential to re–set the prevailing macroeconomic policy orthodoxy.

Much depends on these choices, for the US itself and the world.”

In terms of signposts to date, we note that:

- In trade and foreign policy, there is continuity from the previous administration in terms of the determination to treat China as a rival, and to pursue a nationalistic line on trade more broadly. The lack of action (to date) to rollback tariffs on Chinese goods despite an acknowledgement of their contribution to inflationary pressures has been an interesting test of resolve on this score.

- The current situation in Ukraine has galvanised NATO, the G7 and the broader democratic movement. Prior to this emergency, there have also been clear efforts by the US to re–engage constructively with both immediate allies and with the multilateral architecture.

- Climate action has entered the Administration’s everyday domestic and foreign policy discourse, and the US clearly attempted to lead constructively at COP26. That said, the initial congressional failure of “Build Back Better”, and the trimming back of some climate-related elements of the Bipartisan Infrastructure bill, are reminders that politics is ultimately local. And as the mid–term elections loom, the results of which may increase the complexity of delivering the announced agenda, we note that the Inflation Reduction Bill includes around $370 billion for core elements of Build Back Better. Swings and roundabouts.

- On macroeconomic policy innovation, six months ago we wrote that “The overriding commitment to reflating the economy and creating jobs is clear, with the White House, the Treasury, and the Fed seemingly of one mind on this score. The next step is how to carefully manage the success of the combined policy push, with both growth and inflation on the move. An emerging issue here is that “bad” inflation (as defined above) is now a pressing political concern, with gasoline well above $3 per gallon in early calendar 2022.” With gasoline averaging more than $5.03 per gallon in June–2022 and $4.68 per gallon in July, alongside general inflation of around +9% YoY, countering cost–of–living pressures obviously now predominate in the political calculus. It remains to be seen if the “high pressure economy” experiment returns in the medium term, once there is some assurance that the supply side of the economy is ready to keep up.

In Europe and Developed Asia, the scale of recovery since the deep contractions of the June quarter of 2020 have been respectable viewed as an aggregate, but experientially it has felt quite stop–start, reflecting both additional waves of the pandemic and supply constraints in key sectors. In the bellwether auto sector, where each region is a critical cog in the global value chain, supplier delivery times remain deeply unfavourable versus historical norms, but are past the absolute worst, according to the global sector PMI produced by S&P Global (formerly I.H.S Markit). The backlog of work also appears to be past the peak, but there is considerable catch–up to come before operating conditions can be said to have normalised. This normalisation will be accelerated by softer consumer demand.

Common to the US experience, upstream inflation is painfully evident, while business surveys that had been implying generally favourable operating conditions with respect to demand (if not supply), have taken a notable tumble in recent months. Inflation has picked up most noticeably in Europe, with the energy crisis of the 2021/22 winter quadrupling power prices, with households and industry alike buffeted by this fierce headwind.

Coming out of that winter, spring weather was unable to alleviate energy stress, which has been amplified by the invasion of Ukraine, actual sanctions and self–sanctioning, summer heatwaves, nuclear outages, low river levels, record LNG and energy coal prices and erratic pipeline gas supply. These adverse forces have gripped Europe’s power sector and parts of its heavy industrial sector in a tightening vice. We are approaching the winter of 2022/23 with a sense of foreboding.

Against this backdrop, the ECB waited until July to move interest rates for the first time, kicking off the cycle with a 50 bp increase. The ECB must tread more warily than the US Fed on rate hikes, with the region’s soft underbelly of indebted sovereigns a constraint on freedom of action. The euro has weakened considerably in the face of this differentiation. In stark contrast to the “currency wars” and failed austerity of the 2010s, a weaker euro is not a desirable outcome. Indeed, exchange rate appreciation is the desirable outcome in the scramble to alleviate cost–of–living pressures for households. The ECB faces some very difficult trade–offs in areas where it does have agency and some unpalatable uncontrollables that add considerable complexity to its policy calculus.

In developed North Asia, the manufacturing PMIs ended the 2021 calendar year around 54 in Japan and 52 in South Korea: six months later they are tracking just 1 point lower, at 53 and 51 respectively. Both nations have faced mixed conditions, with a material decline in the terms of trade co–existing with a solid export performance, led by capital goods. There are some cracks emerging in the edifice though, as export markets in the US and Europe have begun to weaken, and the Chinese recovery is not yet fully–fledged.

Japan and South Korea are at the epicentre of the global chip supply chain. They are both expected to benefit directly and indirectly from the ongoing resolution of the global semiconductor supply bottleneck, and progress towards this end has been positive. The semiconductor shipment–to–inventory ratio in developed North Asia is clearly in an expansionary phase, with sales and stocks both advancing apace. While the consumer facing auto and electronics supply chains rightly receive a lot of attention in this space, and these are obviously strategic sectors for both Japan and South Korea, their role as a provider of semiconductor manufacturing equipment and both commodity and higher end chips may be less well known. There is a multi–year boom in chip manufacturing capacity underway, as the world sprints to catch up to escalating demand, and these two economies are at the centre of it, either via new fabrication plants at home, or via exports to Greater China and South–east Asia.

India

India’s economy has been unusually hard to read in the pandemic era. With its distinctive combination of scale and volatility, it was a major swing factor in short term forecasts of global growth across calendar 2020 and 2021. Activity completely collapsed under the lockdown of the June quarter of 2020, with the scale of India’s contraction more than double what China experienced the quarter before. Then activity rebounded smartly from the nadir, and the second half of the calendar year ended up being quite good – and versus expectations, spectacularly good. Tragically, the story soon reversed 180 degrees. With a dramatic re–escalation of COVID–19 cases requiring strict restraints across many major economic and population centres, the economy suffered through another double–digit quarterly decline in the June quarter of 2021. The rebound observed in the wake of the June quarter lockdowns has once again been decent (a double–digit quarterly gain): and the economy was tentatively back on a firmer footing as calendar 2022 opened. Of course, another jolt was waiting at this point as Russian troops entered Ukraine: steep inflation in India’s import bill, principally via high energy, food, and fertiliser prices, with the financial pain amplified by a weakening rupee.

The key takeaway from all these rapid reversals is that India’s recovery trajectory and the associated release of pent–up consumption demand has further to run, rather than being heavily concentrated in calendar 2021 as would have been the case without the June-2021 quarter wave. The question now though is how this release will interact with the challenges presented by tighter global financial conditions, balance of payments deterioration and higher prices for essentials at home. A secondary question is how the corporate sector will respond with their investment plans, noting India is a positive outlier in terms of both services and manufacturing survey data at present, while profitability and credit availability have both improved. Total domestic credit growth has moved steadily higher to around 9.5% YoY, with bank credit running a little faster than the total. Surveys describe a resilient growth picture, with the new orders and output sub–indices in India’s manufacturing PMI recording robust outcomes around 60 in July.

In terms of the numbers, the economy shrank around –7% in calendar 2020 and rebounded around +8% in calendar 2021. Our calendar 2022 estimate is for 8¾% growth.

Indian inflation has lifted sharply, in line with the global trend. The wholesale price index moved into double digit territory in the June quarter of 2021 and has edged higher since. Consumer prices have been holding in the 5–6% YoY range for much of the last year, but have recently breached 7%.

Beyond the short-term uncertainties, returning India to a healthy and sustained medium–term growth trajectory will require a reduction in policy uncertainty, further progress on balance sheet repair, an increase in social stability, a greater focus on unlocking the country’s rich human potential, and an increase in international competitiveness in both manufacturing and traded services.

The emphasis on moving up the “ease of doing business” rankings, and the steps taken to increase India’s share of geographically mobile foreign manufacturing investment are sensible. Labour law reforms passed in 2019/20 are a significant positive for flexibility and simplicity. That should complement the focus on attracting foreign direct investors.

The decision to move away from the controversial farm bills in the face of concerted opposition from rural voters illustrates the difficulty any Indian administration will face as they attempt to establish a more modern and commercialised farm economy23. Alongside the farm bill question, the decision to be less engaged with the regional trade agreement landscape, and inconstant attitudes towards domestic market access for foreign players (be it old, new or green economy), collectively present a mixed message in terms of reform appetite, given the positive impact that freer trade and increased competition would have on productivity growth and innovation. India’s ambitious plans to build an independent renewable energy value chain at home – behind a protectionist wall – as it pursues its newly minted carbon neutrality target of 2070, are a case in point. This choice plays to India’s historical nationalistic economic instincts, but it also fits the post–Ukraine zeitgeist that blends the themes of energy security and decarbonisation. Notably, Indian domestic demand alone is big enough that this introspective effort will not lack for economies of scale. Sub–optimal scale is one factor that can prevent a protected industry from ever reaching the level of standalone competitiveness that allows import substitution to metamorphose into export market gains.

Steel and pig iron

Global steel production was a record 1.95 billion tonnes in calendar 2021, representing growth of 3.7% YoY. China’s production declined abruptly in the second half, with the full year finishing at 1033 Mt, roughly –3% versus the 2020 figure of 1065 Mt. Ex–China production rose 12.3% YoY to 922 Mt, with a broad–based uplift led by India (+17.8%), North America (+16.6%) and Europe (13.6%). In pig iron, the global figure of 1.35 Bt was up 0.7% on calendar 2020, weighted down by a –4.3% outcome in China (869 Mt). Ex–China pig iron increased by 11.4%.

The first half of calendar 2022 has seen YoY growth rates between China and the ROW (rest of world: interchangeable with “ex–China”) converge, after smoothing for the lumpy base effects that afflict YoY calculations. WorldSteel estimates that global steel production achieved a run–rate of 1915 Mtpa in the first half of calendar 2022, or –5.5% YoY. China recorded a run–rate of 1062 Mt (almost the same figure as full–year 2020), or –6.5% YoY. For pig iron, WorldSteel puts the global and Chinese outcomes at 1313 Mtpa (–5.5% YoY, the same rate as crude steel) and 885 Mtpa (–4.7% YoY, firmer than crude steel) respectively.

Six months ago, we wrote that “Our starting point for thinking about calendar 2022 is that a continuation of China’s policy stance of “zero growth” ought to be the baseline, with scenarios built around that. A fourth year above 1 billion tonnes accordingly seems likely, as the nation’s “plateau phase” extends.” Since we penned those words, the authorities have moved the goalposts on the annual production target, shifting from “zero–growth” to a “net reduction”, while remaining silent on the scale of said reduction. There have also been moving parts to reconcile across end–use sectors, feedstock availability and disrupted trade flows, among others. The net impact of these forces on the statement above is that it still feels broadly valid, but the ultimate route to those ends will be a circuitous – and volatile – one.

Broad–based strength across the majority of Chinese end–use sectors in the first half of calendar 2021 gave way to a near universal softening in the second half. Housing starts were particularly weak, and they have remained that way in calendar 2022 to date. Infrastructure has been the lone true bright spot, with other major non–housing sectors (transport and machinery) experiencing shallow contractions. Knowing that information and adding it to the reality of the record run–rates seen in the same half a year ago, it would be reasonable to guess that steel production would have been deeply negative YoY in the first half of calendar 2022.

As a secondary deduction, it would be just as reasonable to assume that China’s blast furnace (BF) utilisation rate would have been pegged at a subdued level. In fact, the opposite has been the case. China’s blast furnace (BF) utilisation rate averaged a robust 84% in the first half of calendar 2022, peaking at 90.2% early in the month of June. And the 84% was achieved despite heavy controls around the time of the Winter Olympics, when nation–wide utilisation hit just 75.4%. Modest demand and strong BF utilisation would tend to point towards rising inventory levels and weak profitability: and this has certainly been the case. However, BF production was partly occupying space vacated by electric–arc furnace (EAF) mills, whose utilisation rates declined by a spectacular –20 percentage points YoY, averaging just 45% versus 65% in the corresponding half of calendar 2021.

The weakness in EAF production was driven by two key factors (1) poor scrap feedstock availability, with collection rates collapsing during the lockdowns, and (2) weak demand for commodity construction steels amidst the downturn in housing activity. These trends combined to hit EAF profitability hard. The difficulties faced by Chinese EAFs saw a reversal of the relative growth rates of pig iron and crude steel seen in calendar 2021, when pig iron lagged crude steel by more than 1 percentage point.

Realised margins for Chinese steelmakers have been poor for most of the half year just concluded, with loss–making widespread at times.

We estimate that spot margins opened the half around +$50/t, but closed it in negative territory, around –$20/t, leading to an average for the period that was very close to break–even. While on the subject of industry financials, as an aside we note that the aggregate liability–to–asset ratio reached 61% in the March quarter of 2022, –9 percentage points from the 70% peak that was reached just before the Supply Side Reform (SSR) of the sector was launched, and just short of the original SSR target of 60%.

We estimate that net exports of steel–contained finished goods account for slightly more than 10% of Chinese apparent steel demand. That is a lower degree of external exposure than, say, Japan or Germany, where the number is about one–fifth. An additional 4% or so of Chinese production is exported directly. The direct trade surplus in steel has fluctuated widely since the pandemic began. It fell into deficit in the middle of calendar 2020, and then rebuilt quickly back towards pre–pandemic levels in the middle of calendar 2021. With an eye to their commitment to restrain growth in total steel production, the authorities stepped in at this point, cancelling export VAT rebates for most steel products and removing import tariffs for semi–finished steel. Net exports recorded a +41 Mtpa outcome for the whole year, with a run–rate of 31Mtpa in the second half. The surplus then jumped again in the first half of calendar 2022, aided by the disruptions in the FSU, with the month of June-2022 recording a sizeable surplus of 84 Mtpa (+68% YoY), and the whole first half coming in at 52 Mtpa.

Turning to the long term, we firmly believe that, by mid–century, China will almost double its accumulated stock of steel in use, which is currently 7–8 tonnes per capita, on its way to an urbanisation rate of around 80% and living standards around two–thirds of those in the United States. China’s current stock is well below the current US level of around 12 tonnes per capita. Germany, South Korea, and Japan, which all share important points of commonality with China in terms of development strategy, industry structure, economic geography, and demography, have even higher stocks than the US.

The exact trajectory of annual production run–rates that will achieve this near doubling of the stock is uncertain. Our base case remains that Chinese steel production is in a plateau phase in the current half decade, with the literal “peak” to be the cyclical high achieved in this phase (with 1065 Mt in 2020 being the “clubhouse leader” in golfing terms).

Strategically speaking, it is the plateau concept, not the peak concept, that matters now. Having attained and sustained 1 billion tonne plus run–rates for three years going on four, defining the literal peak year and/or level is no longer anything more than a tactical question.

There was of course a time in the early to mid–2010s when the peak steel question was at the core of the strategic debate for the entire value-chain. No longer.

We estimate that the growing stock described above will create a flow of potential end–of–life scrap sufficient to enable a doubling of China’s current scrap–to–steel ratio of around 22% by mid–century. The official target of a scrap–to–steel ratio of 30% by 2025 is thus directionally sound, notwithstanding the fact it is more aggressive than our internal estimates by a few percentage points. Uncertainty regarding the future availability of imported scrap (as discussed below in the context of emergent nationalism in major scrap exporting regions), makes China’s official targets a little more challenging.

As we argued in our blog on regional pathways for steel decarbonisation, increasing scrap availability is a powerful lever at the Chinese steel industry’s disposal as it seeks to contribute to the national objective of carbon neutrality by 2060. Beyond the considerable passive abatement opportunities available to it, of which scrap availability is the largest, the decarbonisation choices of Chinese steel mills will be determined by the age of their integrated steel making facilities, the policy framework they are presented with, developments in the external environment impacting upon Chinese competitiveness, and the rate at which transitional and alternative steel making technologies develop. We note that the combined 14th five–year plan for the “raw material industry”, which is more qualitative and less numerically prescriptive than the targets embedded in the 13th, is calling for a carbon dioxide emissions peak before 2030. That is within our base case expectations25. In addition, a guidance document for the steel industry's “high–quality development” has been jointly issued by three official entities: the MIIT, NDRC and MEE.

The document restated the “before 2030” carbon objective, but the 2025 deadline outlined in the draft plan released in calendar 2020 is no longer there. Other industry targets, such as the 15% EAF share in crude steel production and 80% of steel capacity equipped with ultra–low emission facilities remained unchanged from the draft plan. The guidance also reiterated the prohibition of steel capacity growth and the ambition to raise the industry concentration ratio (without a quantified target). Also on the policy front, we expect that steel will be included in China’s ETS before the conclusion of the 14th 5YP period.

Steel production outside China (hereafter ROW) recovered strongly from the mid–2020 collapse, with robust growth (albeit inflated by base effects) of 12.3 percent YoY to 922 Mt in calendar 2021. That compares to 882 Mt in calendar 2019. During the 2021 recovery phase, ROW capacity utilisation rate tracked very mildly above normal pre–pandemic ranges (72–75%) throughout the year. This positive impetus flowed through to the early months of calendar 2022, with utilisation still registering at 74.1% in February, with attractive margins across multiple regions. With hindsight, that month looks like the mini–peak for this cycle, with utilisation trending lower sequentially in the remainder of the half, with June–2022 hitting an underwhelming 68.5%. That was the first reading below 70% in 20 months. The run–rate for the full half (852 Mtpa) is –4.2% YoY.

India’s crude steel sector has recovered strongly from the pandemic, and it has also exhibited resilience amidst the current slowdown. After growing by +18% to 118 Mt – a record – in calendar 2021, year–to–date output in calendar 2022 has lifted a further 8.8% to a run-rate of 127 Mtpa. Pig iron has increased by a lesser +3.5% YoY to 81 Mtpa on the same basis. Output in Japan, Europe and South Korea has decreased by –4.3% (pig iron –6.2%), –5.9% (pig iron –6.7%) and –3.9% (pig iron –7.7%) YoY respectively. The US has been somewhat more resilient, backed by generally strong profitability behind its tariff wall, with crude production falling only –2.2% YoY.

The turnaround in fortunes has been swift. In the immediate aftermath of the invasion of Ukraine, according to Platts, benchmark prices in India (ex–tax), Europe, and the US had surpassed US$1000/t, US$1,500/t, and US$1,600/t respectively. These figures have since retreated to below $800/t, $900/t and $1000/t respectively as of July–2022: all below the levels prevailing in February just prior to Russian troops crossing the border.

The abrupt ending to the strong run of profitability across calendar 2021 and the March quarter of 2022, which had provided a fillip to a number of struggling mills after some very tough few years both prior to the pandemic and then in calendar 2020, could have far–reaching consequences. Improving cash flow had enabled a tangible acceleration of deleveraging efforts and boosted shareholder returns. It may also have sparked more ambitious decarbonisation efforts, the financing of which has always been a question mark in this traditionally low margin sector. If the profitability sweet spot is over – and this is a point of uncertainty – we are back in a world of significant trade–offs.

Protectionism remains a feature of the ROW industry landscape, with both export and import disincentives in play, with the latter persisting despite elevated inflationary concerns. There is also an emerging theme at the nexus of decarbonisation and protectionism: scrap nationalism.

There is speculation that the EU may be contemplating a scrap export ban. Mandated circularity of local waste generation, including scrap metals, or establishing stringent conditionality on trade in waste, are other potential levers26. Were bans or “hard” domestic prioritisation to occur in major export regions, thereby materially reducing the availability of scrap imports in developing nations (whose domestic scrap generation capability is limited by their low stocks of steel in use27), it would incentivise the building of new blast furnaces (average emissions profile being around 2.0 tonnes of CO2 emitted per tonnes of steel) rather than EAFs (about a quarter of the emissions of an unabated BF – and even lower if using zero or low emissions power). It would be perverse if decisions were made in Europe seeking to assist the local industry to pursue transitional rather than end–state technology, while developing nations are left stranded from some of the feedstock that would allow them to bring about an early step change in the emissions profile of their young and expanding fleets.

As we are fond of saying – both because it is true and also because it serves as a timely reminder and reality check for Eurocentric views – the decarbonisation battle cannot be won in Europe alone, but it can certainly be lost in the developing world. That is particularly true of steel.

That is why we are focussing our Scope 3 research and development partnerships in steelmaking on Asia, where our five MOU partners to date represent around 13.4% of reported global steel production, almost 6 percentage points more than EU production combined. Unsurprisingly, their share of global pig iron production is even higher. Looking at our partners via the nations they represent rather than as standalone entities, around 70% of crude steel production is covered and around 80% of pig iron.

Our approach to ranging uncertainty regarding the future pathway for steel decarbonisation remains to blend bottom–up, regional analysis leveraging our deep corporate knowledge of this sector with two other pillars of our proprietary foresight method, which are scenario analysis and framework design. The results have been discussed here and here, as part of our Pathways to Decarbonisation blog series. Where our findings differ from others in steel, it is often due to our differentiated regional approach, which is supplemented by the insights we glean as a key cog in both the Asian and European steel value chains.

On the topic of decarbonisation more broadly, our latest research shows a modest net uplift in our base case for long term steel demand from the combined impacts of:

- Rising investment in the infrastructure of decarbonisation [+]

- Lower demand from the fossil energy value chain (e.g., upstream petroleum) [–]

- Higher capital stock turnover as the lifetimes of equipment and structures are reduced by the harsher physical conditions they are expected to endure based on projected climate change in coming decades. [+]

- Lower growth rates in GDP versus baseline due to the physical impacts of climate change and the imposition of carbon policies [–]

We will detail this research in a forthcoming blog.

Iron ore

Iron ore prices (62%, CFR, Argus) traded a reasonably wide range over the second half of financial year 2022, with the spot index ranging between $110/dmt and $160/dmt, averaging around $140/dmt. Even so, that represents a considerable reduction in volatility from the prior half, when the range was $223/t to $87/t. Half–on–half average prices were quite close (a $3/dmt difference), but versus the corresponding half of financial year 2021, they were –$44/dmt lower. As for fines, lump premia traded in a narrower range in the second half of financial year 2022 ($0.09 to $0.45/dmtu, averaging $0.30/dmtu, seaborne).

Six months ago, we recounted the abrupt correction in the iron ore market that occurred in the face of steep cuts in Chinese steel production in the second half of calendar 2021. This negative demand shock had a major impact on the balance of the seaborne trade, which flipped from deficit to surplus essentially overnight. Chinese port stocks of all iron ore products28 closed the calendar year 2021 at 156 Mt, substantially higher than the closing positions of 124 Mt for calendar year 2020 and 122Mt for the first half of calendar year 2021. At the opening of calendar 2022, with seaborne supply expected to increase and demand expected to be constrained by both special factors like the Winter Olympics and the overall zero–growth mandate for steel, there was a general view that even with firmer end–use conditions, port stocks were likely to rise further.

As it so often does, the invisible hand of the market chose a different course to the one dictated by careful logic. Rather than building up, port stocks trended downwards for four straight months after peaking around 160 Mt in February 2022. At the end of this run, port stocks hit 126 Mt, close to the year–end positions for calendar 2020 and 2021. How did this happen? Three main factors drove the surprisingly firm iron ore fundamentals: (1) stronger than expected demand on the back of elevated BF utilisation rates in China, partly due to scrap shortages that hindered the EAF fleet; (2) lower than expected aggregate seaborne supply from low–cost majors; (3) lower than expected aggregate seaborne supply from junior and swing suppliers, including India [export tariffs] and Ukraine [military conflict].

Against this backdrop, Chinese domestic iron ore concentrate production (implied) has been steady. It reached 308 Mt in both 2020 and 2021. We anticipate a similar or slightly higher figure across calendar 2022, although there will need to be some catch–up in the second half to achieve that after COVID–19 disruptions in the first half.

Going forward, we expect that in addition to structural market–based drivers, potential policy initiatives that seek to increase China’s self–sufficiency in ferrous units, as well as safety and environmental inspections are likely to have a material influence on the average level and period-on-period volatility of Chinese domestic iron ore production. In this regard, we note that fixed investment in iron ore mining surged 76% YoY from Jan–June 2022. This is presumably in part a response to the ambitious targets in CISA’s “Cornerstone Plan” for 2025, which aims to lift both domestic iron ore and overseas equity–controlled volumes by 100 Mt versus a 2020 baseline. Our take on the domestic component of the goal is that it will be challenging to achieve, based on a bottom-up review of potential projects29.

Moving to differentials, the lump premium (LP) was firm in the March quarter, supported in part by sintering restrictions in northern China. The LP then trended lower from the mini–peak of $0.45/dmtu in mid–March. The lifting of sintering restrictions, weakening steel margins, and rising seaborne supply all contributed. The LP closed financial year 2022 around $0.10/dmtu.

Fines differentials to the 62% index for the 65% and 58% indexes narrowed across the second half of financial year 2022 (lower premiums for higher grades, smaller discounts for lower grades) following the deterioration in steel margins and the consequent move by mills to procure lower cost raw materials on average.

Looking ahead, the key near–term uncertainties for iron ore are the pace of steel end–use sector recovery in China, how the Chinese authorities will administer steel production cuts in the remainder of the 2022 calendar year, and the performance of seaborne supply: mostly but not exclusively with regards to the seaborne majors.