10 noviembre 2019

Oil is a highly attractive commodity in the 2020s; and it will remain so in the 2030s, beyond the projected peak in demand, albeit not quite to the same degree.

Our previous post on the fundamentals of the oil market, published in February of 2017, was entitled “Last In, First Out”. That phrase paid homage to the industry’s oft observed ability to rebalance itself in a timely manner following the emergence of cyclical excess supply.

A large element of that previous edition of Prospects, perhaps inevitably so given operating conditions almost three years ago, was devoted to the cyclical impact of US onshore supply elasticity on global price dynamics. We expressed a view that core US shale plays would remain a key force in the determination of who would provide the marginal barrel to the oil market for another half–decade or so. That dynamic promised to cap prices for that period somewhat below where we saw the long run equilibrium. However, looking beyond the “shale moment” – which hindsight will probably demarcate as a disruptive decade from the first quarter of the 2010s to the first quarter of the 2020s – we stated that we saw “compelling market fundamentals” emerging beyond that time. Those fundamentals encouraged us to both invest and explore counter–cyclically. We sustained this approach through the low point in prices and the much more extended trough in deepwater capital and exploration costs. A disciplined approach to targeting our exploration efforts has led to a very competitive rate of discovery from these counter-cyclical operations. The option set we have accumulated, and our broader liquids portfolio, is discussed in more detail here.

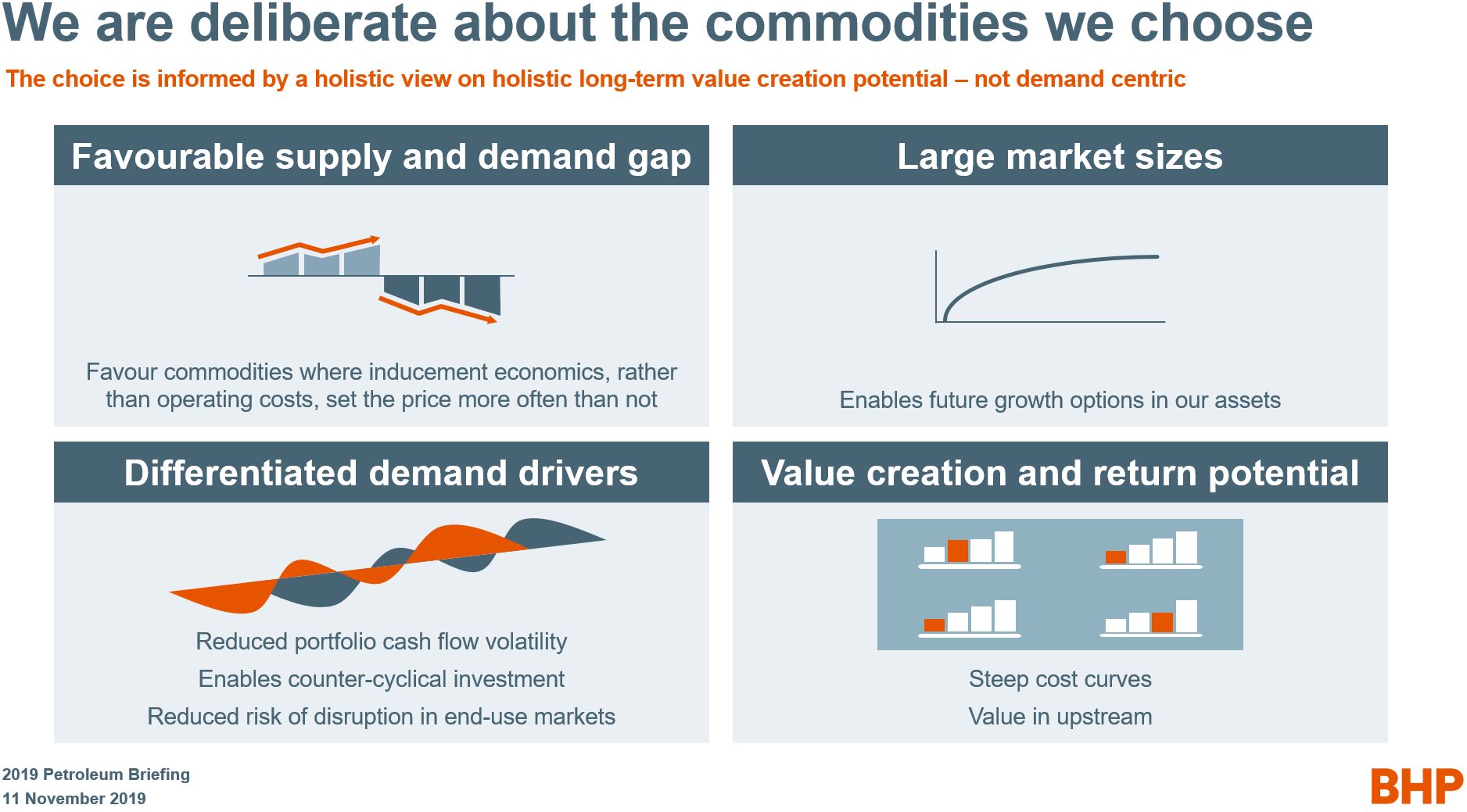

Our basic framework for oil attractiveness is summarised in the animation below.

At the heart of our fundamental attraction to oil is the structural gap between supply and demand we see extending across future decades.

At the heart of our fundamental attraction to oil is the structural gap between supply and demand we see extending across future decades, based on our internal analysis. In the 2020s, it is expected to be roughly 4 percentage points per year, with 1 per cent growth in demand set against –3 per cent decline1. Once demand peaks – in the mid–2030s in our central case (or the mid–2020s in the low) – demand could fall by around –1 per cent per year, but decline rates, of course, would either remain the same or steepen. That would leave a smaller but still material 2 percentage point gap – at a minimum - on an annual basis. That implies very strongly that the oil industry will be in an inducement pricing regime more often than not. And when the final decile of the cost curve is so steep, that could lead to robust margins for incumbent producers in the upstream segment of the value chain. And if the industry were to slow down the relentless pace of reserve renewal that is required to sustain, let alone grow production for any material length of time, the possibility of being caught short of oil a half-decade to a decade out from any such “pause” could become very real.

Cost curve gradients say a lot about a commodity. In oil, it principally highlights two core characteristics that are related to each other: heterogeneity and scarcity.

Cost curve gradients say a lot about a commodity. In oil, it principally highlights two core characteristics that are related to each other: heterogeneity and scarcity.

Let’s talk about heterogeneity. It all starts with the diversity of the geology. That leads to the need to develop a variety of extraction techniques suitable for the efficient extraction of the various types of deposits, or reservoirs, encountered. That then leads to differences between the various blocs of the cost curve. These differences can be stark. For example, the cost of inducing new supply in non-core shale resources is approximately three to four times higher than in conventional onshore assets in the Middle East. These deposits are prominent in the tenth decile and first quartile of the cost curve respectively. Intuitively, one might expect that gap to widen and narrow pro-cyclically. Empirically, we can state that the intuition is broadly correct, and the issue is most evident during the upswing of a price cycle.2

What of scarcity? The road from heterogeneity to scarcity is a short one. First, it is stating the obvious to say that both economy of effort and commercial logic dictate that if society’s needs could be met solely through oil deposits that were both easily to find and cheap to extract, they would be. As the world actually meets its demand for oil in a range of ways – the development of which has required both a large amount of capital and a great deal of ingenuity - the logical inference is that the underlying resource must be scarce. At the very least, it infers that idle deposits that meet the ideal of “known fields that are low cost under current technology” are finite.

This concept comes through very clearly when one takes a long term view of supply.

One fact to dwell on is that a considerable part of today’s lower cost sources of supply are expected to need replacing by the late 2020s. Another is that we just don’t know exactly where a material fraction of supply will come from through the 2030s and 2040s. The inherently optimistic industry term for this growing future wedge is “yet-to-find”. Advances in general purpose technologies like machine learning, greater computing power and industry specific progress in exploration technique will come to together to help address the rising challenges. But as the relative lack of offshore exploration success enjoyed by the industry since the early 2010s illustrates, we cannot glibly assume that oil will always be found, developed and delivered to markets right on cue. Right hand side tail risks on price have by no means been permanently subdued, as recency bias honed during the “shale moment” might predict. While discretionary spare capacity held by some major producers could mitigate this cyclical risk to some extent that is a fragile foundation on which to build a long term strategic view.

The challenges presented by scarcity, allied to the tyranny of on-stream field decline, have led to alarmist, and technically if not arithmetically naive theories of peak oil production tending to crop up from time to time. That is not something that emerges spontaneously if the underlying resource is abundant! Simply put, oil is not easy to find, and when you do find it, it is often complex, costly and risky to produce. Even so, more recently, with the transport electrification mega-trend in play, when the words “oil” and “peak” occur in the same sentence, the premise is almost always demand. We will return to the demand theme below.

The combination of potential difficulties we present above are in fact precisely what attracts us to oil. Complexity may not attract everybody, but to us this promises rewards for those with experience and world class capability in resource discovery and conversion. There are no sustainable shortcuts for attaining this blend of capabilities. We have won ours by operating in this commodity since the 1960s. Oil suits us.

We anticipate that global oil demand could peak in the mid-2020s in our plausible low; and in the mid-2030s in our mid case.

So what of demand?

First, a few round numbers based on data from the International Energy Agency. Of the approximately 100 million barrels of oil consumed each day around the world, around 47 million are used in road transport, with light duty vehicle (LDVs) taking around 28 million of those and medium and heavy duty vehicles (MHDVs) taking the remaining 16 million. Next in the demand stack comes non-road transport, led by aviation and shipping, with the collective accounting for another 16 million barrels or so, taking total transport up to 60 per cent of demand. Feedstock (around 11 million), comes next. Residential and commercial and industry are in the mid-to-high single digit million range. Power and agriculture explain most of the remainder.

Road transport is clearly the first priority in terms of understanding demand trends. To that end, we released the third episode in our electrification of transport series today to complement this blog. The first episode covered our updated views on the electrification of the light duty vehicle fleet. The second episode zoomed in on the battery chemistries that we expect to lead this change. The new episode looks at the outlook for the electrification of medium and heavy duty vehicles – a huge but in our view under-studied element of demand.

Our conclusions, which you can read about in detail here, are that buses are likely to electrify on a similar trajectory to LDVs; medium duty trucks will follow, but on a less aggressive path initially; while heavy duty trucks “will represent the final frontier in terms of the EV conquest of road transport”.

On the other key demand categories, substitution and disruption risks vary widely. For instance, it is easy to substitute in power, possible to disrupt feedstock through more pervasive recycling of plastics3 and very hard to substitute or disrupt in aviation. We range demand in these segments based on challenging but plausible assumptions on these risks, and the internally consistent group wide macro view appropriate to each case. The results are that we anticipate that global oil demand could peak in the mid-2020s in our plausible low; and in the mid-2030s in our mid case.

To put a peak in oil demand into context in terms of market size and total energy requirements met from this source, over the three decades to 2020, we estimate that around 900 billion barrels of oil were required, cumulatively, to support rising living standards around the world. In the 30 years to 2050, in the era encompassing the peak, our low case projects that just over one trillion barrels of oil will be needed. Our mid-case adds approximately 250 billion barrels to that conservative base. As illustrated above, given the geological realities of this commodity, that is no small challenge. We make no apology for continuing to playing a constructive role in the provision of the energy that the world requires, even as the decarbonisation mega-trend unfolds.

In closing, it is worth reiterating the contours of our plausible low case for oil, as shared with readers of Prospects at the time of our full year annual results. It is this case that is used to gauge the resilience of investment decisions under the Capital Allocation Framework.

Our low case for the oil price is predicated on OPEC running without discretionary spare capacity; high case EV penetration [well above the vast majority of published mid–cases]; trend increases in fuel efficiency in the traditional fleet; low case macro inputs constraining non–transport demand; a conservative weighted global decline rate assumption of –3 per cent; and a demand peak in the mid–2020s, a full decade ahead of the central case.

[1] This assumption is conservative. Many organisations assume a higher rate of decline, in the range of 5 to 8 per cent.

[2] We note that US onshore costs quickly rose back to 85% of the prior cyclical peak for all-in levels, running 15 percentage points above US deepwater. Our high case for US deepwater capital costs in the mid-2020s is roughly 90 per cent of the previous cycle peak.

[3] Our research on the strategic theme of the Circular Economy is ongoing and we will share our thinking with readers in due course.