10 noviembre 2019

In this episode of Prospects, we dive into the complex question of LNG attractiveness.

Our conclusion is that LNG can be an attractive exposure to the global gas market if you are the owner of an advantaged portfolio of assets.

BHP’s integrated view of the global energy system sees global gas demand continuing to grow out to mid-century, with the LNG segment growing faster than the total.That stands in contrast to oil, where we see demand peaking in either in the mid-2020s (low case) or the mid-2030s (mid case). The diversified nature of gas consumption, and its advantageous carbon profile within the fossil fuel universe1, are its core strengths. Demand is balanced across power generation, buildings (household and commercial) and industrial applications, allied to some emerging niches such as shipping2.

The global gas market is big and getting bigger – and the LNG share of the market could almost double to around one-fifth by 2050.

The global gas market is big and getting bigger – and the LNG share of the market could almost double to around one-fifth by 2050.

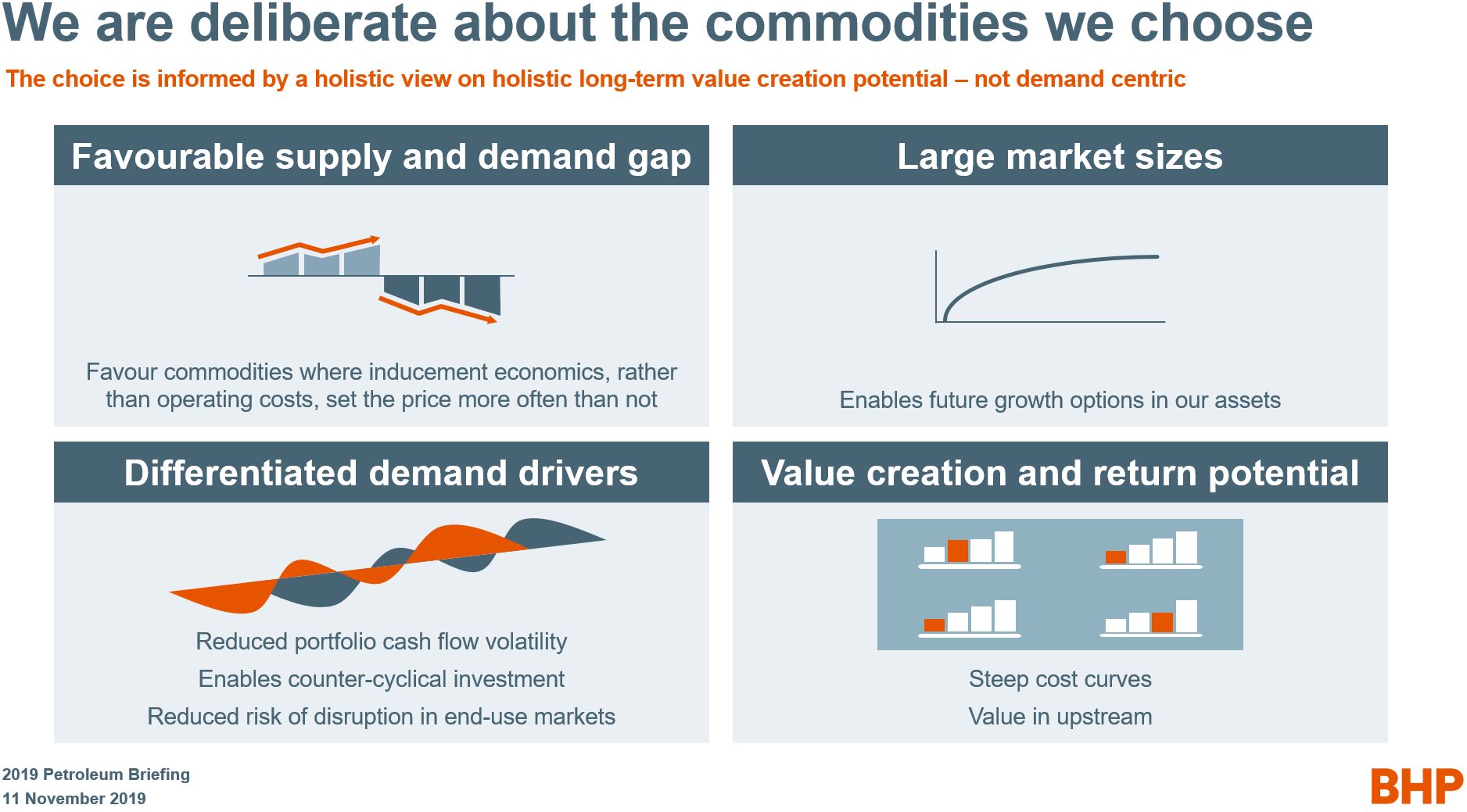

Demand, of course, has never been an issue where gas is concerned. Our commodity attractiveness framework though explicitly rejects demand-centric assessments. Instead, we focus on what the future supply-demand balance says about the likelihood of the market being in “inducement” more often than not. We combine that analysis with assessments on the future size of the market; the presence of diversified drivers of demand vis-à-vis the rest of our portfolio; upstream focussed value chains and long run margin potential. Margin potential is reasonably approximated by the shape of the long run cost curve.

Much of that is straight forward – with the exception of “in inducement more often than not”. So what do we mean by that?

There are two basic price formation regimes for commodity markets. An inducement pricing regime is one where marginal supply in an industry is being met by new projects. New projects require an expected return that, at a minimum, allows the developer to pay-back up front capital outlays and service ongoing creditor commitments. The price that solves for that required return is the “inducement price”. We also refer to this concept as “long run marginal cost” – LRMC. The second price formation regime is one where marginal supply in an industry is being met by existing projects. At a minimum, existing projects require compensation only for their short-run marginal costs – SRMC – which are, by definition, lower than LRMC. Therefore, the margin which an incumbent producer can reasonably expect to earn in a LRMC price regime is higher than under SRMC – and thus we prefer industries where LRMC is expected to govern the provision of marginal supply most often.

So where does LNG fit? It’s complicated.

First of all, we observe that a positive demand trajectory coupled to systematic on-stream decline creates a structural supply-demand gap across all our cases. That implies, prima facie, that the LNG market meets the most important criterion for an enduring inducement pricing regime.

That prima facie case is just the start of the conversation. The underlying resource is geologically abundant.3 Upstream and midstream technologies are homogenous across the globe. A new, global scale LNG project is large vis-à-vis the size of that particular segment of the industry, although the same issue does not arise for global gas proper. These characteristics argue that despite the projected trend supply-demand gap, under a plausible chain of logic the LNG industry could easily find itself in a SRMC world for an extended period of time. That logic might include an excess of committed supply targeting a projected future inducement window, thereby materially delaying its appearance; or demand under-performing expectations, for either macro or industry-specific reasons; or decision making by key actors being led by motivations other than pure commercial returns; or some combination of the above.

How do we synthesize that? The answer is that we foresee the LNG industry undergoing a number of inducement waves in the coming decades, as demand growth and base decline grind away, but these waves will be interspersed with pricing lulls that could be extended due to the lumpy nature of the prospective supply response leveraging off the abundant underlying resource. So while we are confident that industry will need to induce considerable new supply, we can’t be adamant that it will be in inducement pricing “more often than not”.

Advantaged assets are those that are already operating and are favourably placed on the cost curve; or for new projects, those positioned to reduce capital intensity through tie backs to existing infrastructure, whether owned or where third-party ullage is available on fair commercial terms.

The plausible low case forecasts that underpin our Capital Allocation Framework are the practical embodiment of this method of thinking. In our most recent Outlook blog, that complements our six monthly financial reporting, we introduced readers to the contours of our low cases across the major commodities in our world-class portfolio. This is the narrative for LNG:

Our low case for the LNG price is predicated on Qatar executing a market share strategy via the accelerated development of its North Field; Russian pipelines into Europe increasing market share by five percentage points; a low case macro environment curbing industrial and power demand; a ‘low carbon’ case for renewables penetration competing with gas in the power sector; and a cluster of optimistic FIDs by ‘portfolio players’; all of which serves to delay market balance by one full development cycle [from our central case timing of circa 2025].

It is obvious that if inducement pricing proved elusive for extended periods of time, highly capital intensive greenfield projects with long dated paybacks even under benign operating conditions would see their returns disappoint.

The conclusion is then that only advantaged assets will be truly resilient if future operating conditions prove to be underwhelming. Advantaged assets are those that are already operating and are favourably placed on the cost curve; or for new projects, those positioned to reduce capital intensity through tie backs to existing infrastructure, whether owned or where third-party ullage is available on fair commercial terms. Favourable geographic positioning for access to gas-constrained consumer markets is an additional source of advantage. Assets that do not meet the above description will find it difficult to compete effectively for capital within BHP’s portfolio of high quality options.

Another issue that we have raised as part of our strategic foresight program4 relates to the conventional wisdom on long run gas demand. Insights derived from our investigation of the strategic theme of power decarbonisation have led us to question whether gas’ future role as a transitional source of base load in emerging markets is sacrosanct. Our investigations concluded that it is just as easy to envisage emerging markets with a young coal power fleet leap-frogging straight to renewables when those plants are due to retire. That doesn’t completely take away the growth premium enjoyed by gas in the long run, but it does take a little of the shine away. That observation is most relevant for mega-LNG projects where a material element of the value is derived in from the mid-2030s and beyond, when such leap-frogging might occur.

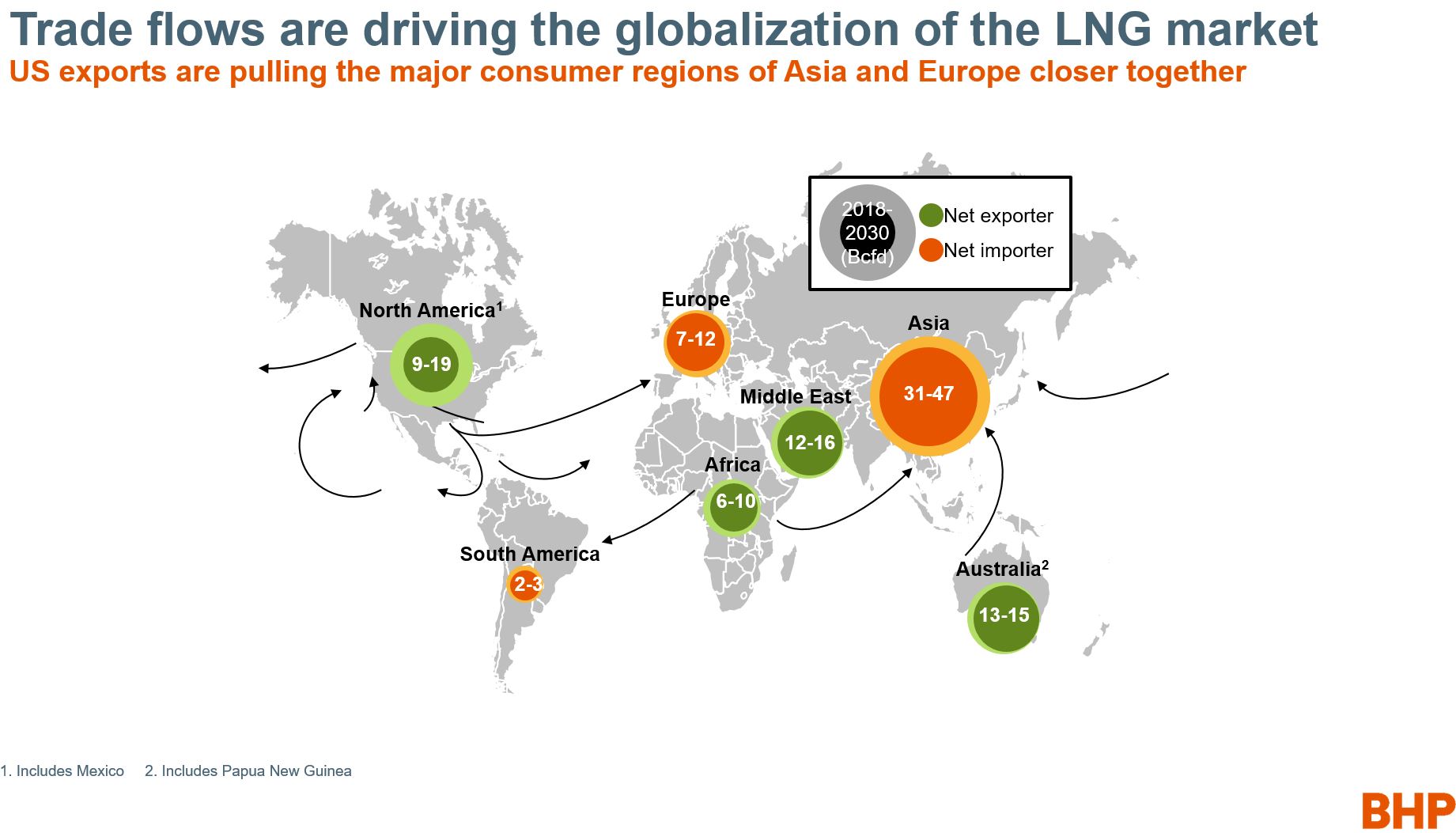

There are additional characteristics of the LNG industry that will need careful watching over the coming decade. The overarching trend is globalisation. This is most evident in the accelerated move towards price harmonisation in the last few years.

In the fullness of time, we feel that a global benchmark will become the natural pricing mechanism for traded LNG.

Going back a step or two, gas markets have historically been highly regionalised, with indigenous and pipeline import supply largely sufficient in the major geographies. Depleting indigenous resource bases, a desire among customers to reduce concentration risks from cross-border pipelines, the strong price and demand signal in the late 2000s, early 2010s, that arguably led to both the US shale revolution and the era of mega LNG projects in Australia, and the US’ accelerating tilt towards exports, have had a cumulative disruptive force on the historical dynamics. While pricing remains nominally regional today, with a considerable portion of sales still under long-term contracts, many of which remain oil-linked, global harmonisation is coming swiftly to the “islands” of North America, Europe, Asia and [eastern] Australia.

The introduction of flexible destination cargoes, the optimisation strategies of global equity portfolio players, more liquid spot markets and the increasing willingness of producers to sanction projects without sales pre-commitments, are all contributing to the process. In the fullness of time, we feel that a global benchmark will become the natural pricing mechanism for traded LNG . Henry Hub is one of the candidates for this longer term role, given the prominent nature of US export projects in the provision of marginal supply across our various cases. Alternatively, a marker price from a major consumption region, either Europe or North Asia, could eventually fulfil this function. Domestic markets such as eastern Australia, which are already being influenced by this transition, will be even more closely linked to international LNG pricing as these global forces roll onward.

[1] On this point, where one draws the emissions boundary becomes critical. We expect that the world will ultimately move towards the regulation of full cycle emissions, which will narrow gas’ advantages versus coal and oil, but not erase it entirely. See chapter 7 of the IPCC report behind the link, in particular table 7.6. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/ipcc_wg3_ar5_chapter7.pdf

[2] BHP sees LNG bunkering as a very promising vehicle for improving the environment footprint of the maritime bulk trade. Indeed, our maritime business recently released an LNG-only tender for around 10% of our prospective iron ore tonnage out of Western Australia.

[3] It is also a by-product of oil production, and therefore can suffer from the unintended consequence of decisions made with reference to the dynamics of another industry. The relative “gasiness” of oil plays in onshore US has brought this issue to the forefront in the Henry Hub market over the last decade.

[4] Alternative methods of foresight, which are distinct from business-as-usual range forecasts, were discussed in briefings on our Capital Allocation Framework and Strategy respectively.